Is this the biggest mystery in the 150 years of the Kentucky Derby? Where is Aristides buried?

Nancy Herndon-Ulrich was 275 miles from Derby City, but she sensed what I wanted as soon as we got on the phone.

“You’re looking for Aristides, aren’t you?”

Every couple of years, horseracing fans and historians turn to Oakland House Museum in St. Louis searching for the gravesite of the first Kentucky Derby winner. Aristides lived on the estate for three years in the late 19th century, and several articles, blogs and message boards claim he’s buried there.

But Aristides' final resting place has never been found.

In the 131 years since the champion’s death, the mystery of his final resting place has left a chaotic trail. The Kentucky Derby Museum, the historical authority on the race, can’t definitively say what happened to his remains. Meanwhile, the internet is full of theories. In the months leading up to the 150th Kentucky Derby, I followed the threads of that mystery hoping to track down Aristides' grave or, at the very least, how it became lost to time.

Herndon-Ulrich, the president of the historical society that runs Oakland House, has no reason to believe Aristides ever returned to the property after he was sold in the early 1890s. There’s no record or evidence that he was ever buried on the grounds.

Even so, she hoped I’d find him.

I did, too.

“Poor Aristides,” she told me, kindly, when we spoke on the phone. “He’s so glorious and [it’s a shame] to just have his information lost.”

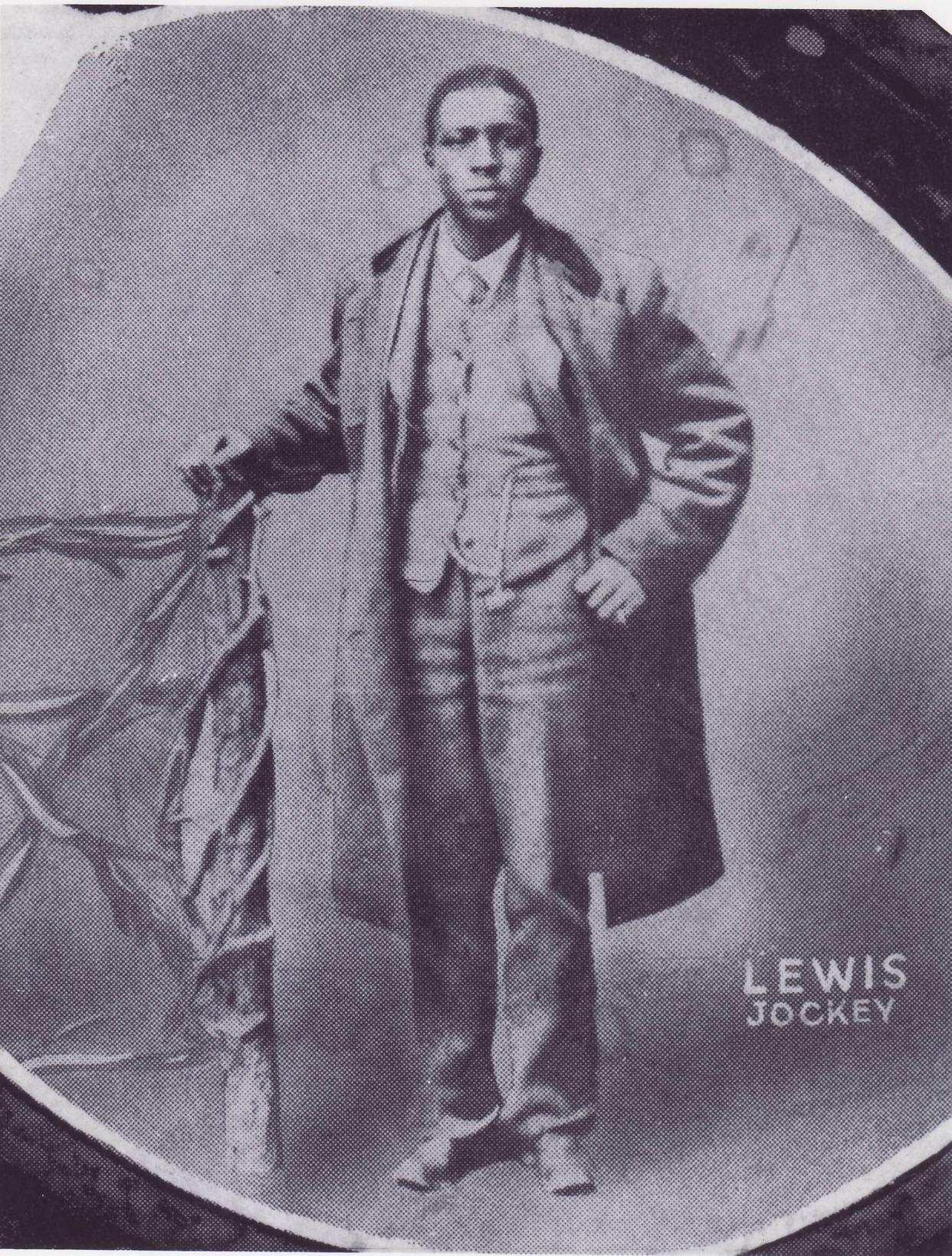

In 149 years since Aristides and jockey Oliver Lewis won the first Kentucky Derby, the race has blossomed into the longest, continuously held sporting event in the country. Other winners such as Secretariat and Barbaro have graves that are visited and revered.

Aristides' memory lives on in the bronze statue at Churchill Downs, the storied track where the race is run each year, and in name at its indoor Aristides Lounge. A residential street is named after him in Louisville's South End.

The desire to honor him is certainly there, but his bones are seemingly nowhere to be found.

Where did Aristides the first Kentucky Derby winner die?

Aristides' death notice ran in newspapers throughout the country in the summer of 1893, and clicking through all of them on newspapers.com three things became abundantly clear.

Aristides died in St. Louis at “the Fair Grounds.”

He was “a failure as a stud.”

There was a lot of confusion about who owned him.

Jessica Whitehead, the Kentucky Derby Museum's curator of collections, has managed to track his ownership much better than the journalists of 1893.

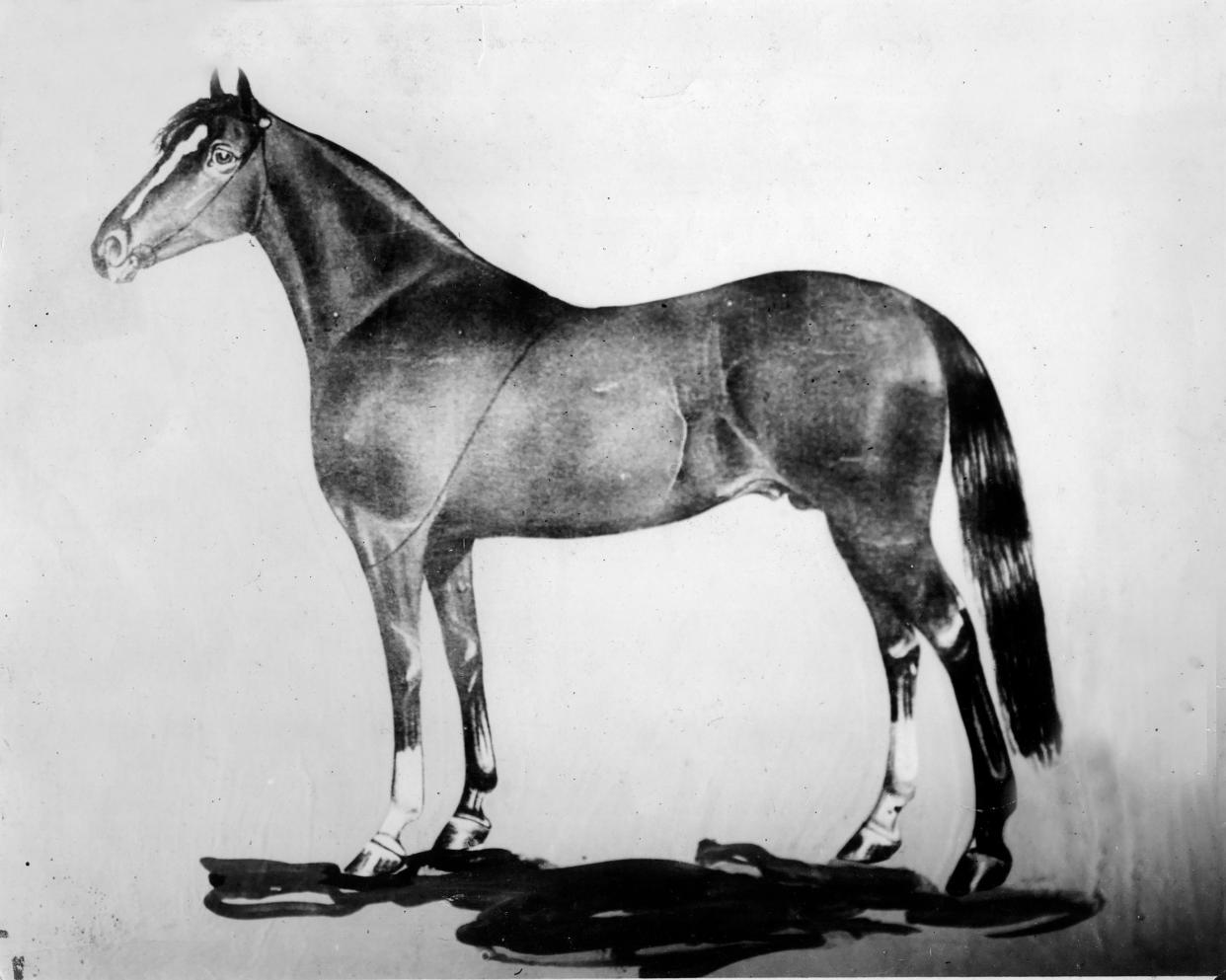

Aristides' was foaled at the McGrathiana stud farm in Lexington. The "little red horse" is more known for being the Kentucky Derby's first winner than for his skill. He raced 21 times and garnered nine wins before retiring after an injury in 1877.

From there, Aristides returned to McGrathiana to stud, and if the timing had worked in his favor, his grave might still be there today. McGrath had a soft spot for Aristides, Whitehead explained, and he was among horses paraded around for guests during elaborate burgoo parties. The horseman also buried some of his favorite horses on the grounds.

But McGrath died in 1881, and Aristides was sold to a farm in Porter County, Indiana. He stayed there until 1884 when James Lucas Turner of Kinlock Farm in St. Louis purchased him. When he died, Turner's wife Bertha inherited him.

The records Whitehead found show she sold him to a farm in central Missouri ― for either $50 or $1,300.

By this point, Aristides' reputation was souring. His progeny never remotely matched his talent on the track Whitehead told me. Either price was plausible.

Less than a year later, Robert S. Brookings purchased Aristides and brought him to the 476 acres at Oakland House. Herndon-Ulrich described Brookings as a “city gentleman, who was playing in the country.” He left for Washington, D.C. in 1893.

In the final year of his life, Aristides was sold at least three times, and Whitehead believes one man in that mix owned him for less than a day. His last owner, J.J. Carter, purchased Aristides on June 3, 1893, and the 21-year-old horse died three weeks later.

His final two owners both had stables at “the Fair Grounds," and the vagueness there is where one of the most common misconceptions about Aristides' grave begins. Posts and articles commonly confused “the Fair Grounds” with St. Louis’s acclaimed Forest Park, the site of the 1904 World’s Fair. Some even go as far as to say that the grounds around Oakland House were later developed into Forest Park.

Neither one of those things is true. The construction dates and the overall geography don’t line up. The now defunct “Fair Grounds” is Fairground Park, which is 5 miles north of downtown St. Louis. Today, it’s a city park, but in 1893 it was the home of the St. Louis Jockey Club, stables, and St. Louis’s first zoo.

Two days after Aristides died, The St. Louis Globe-Democrat ran a small story about happenings at the jockey club.

When I read it, I thought I’d discovered where the lost champion had gone, and it wasn't to a place of honor.

“Wednesday after the death of Aristides at the Fair Grounds, Capt. Bellairs wired Judge J.J. [Carter] at East St. Louis: ‘When will it be convenient for you to remove your horse Aristides from the track? He will require a carriage.’”

It continues.

“Judge [Carter], not knowing of the once-famous horse’s death, wired back: ‘Please furnish a carriage for old Aristides for the good he has done, and send the bill to W.O. Parmer, Nashville.’”

And then to my horror…

“When the Judge found yesterday that the ‘little red horse’ had begun his journey to the glue factory he acknowledged the joke was on him.”

Had he really ended up in a glue factory?

With a knot in my stomach, I sent the digital clipping to Whitehead, who patiently, calmed my nerves.

“My guess is that's some good, old-fashioned newspaper hyperbole or a joke, albeit, not a really funny one to us,” she replied. “I am guessing that this was a pseudo-story poking fun at poor Aristides being shuffled around by owners so much, and pretty much forgotten, at the end of his life.”

Neither of us was sure who W.O. Palmer in Nashville was or why he was in on this joke. Based on the context, we thought he could be a buddy of Carter’s. Perhaps, Palmer had encouraged Carter to buy the aging champion only to have him die three weeks later?

I wondered if Aristides had left the St. Louis Jockey Club in a carriage and where he might have gone. Digging up anything there proved much harder than I thought.

How are racehorses buried?

Even with modern technology burying a 1,000-pouind horse is no simple task.

Burying a horse in full requires a trench 7 feet wide and 9 feet deep, according to the United Horse Coalition. Backhoes are used for that kind of digging, and that machinery wasn't invented until the late 1940s. Today, most horses are cremated. If they are buried typically only the horse’s head, hooves, and heart go in the grave.

With that in mind, I reached out to the University of Louisville and the University of Kentucky hoping someone in their archeology departments could explain what Aristides' grave might look like. I checked in with the national Association of Zoos and Aquariums, too, thinking someone might know of a historian, who could speak to late 19th-century carcass disposal.

No luck.

“It's a desert out there about it, isn't it?” Whitehead mused as I relayed all of this to her.

Very much so.

You may like: Courier Journal publishing '150 Years of the Kentucky Derby' coffee table book. How to pre-order

So, then I chipped away at the only horse burial ground from that era I knew about — the one Aristides, in theory, would have had a claim to, if McGrath had lived longer.

The old McGrathiana farm is now part of the University of Kentucky’s Coldstream Research Campus in Lexington. All the known horse gravesites have headstones dated decades after Aristides' death, but older unmarked graves are believed to be on the grounds.

There's an intriguing story about Hanover, who retired in 1889 as America’s greatest money-earner of the time. When Hanover died in 1899 — just six years after Aristides — he was buried in full near his stall at McGrathiana, according to a Lexington Herald-Leader story from January 1962. Hanover didn’t stay there long, though. A few years later his skeleton was “exhumed amid mutterings of superstitious grooms who feared bad luck would strike the farm because of such ghoulishness.”

Maybe the easiest way to bury a 1,000-pound animal in 1893 was to dig the grave near the stall where it died.

So, I tracked down a hand-drawn map of the St. Louis Jockey Club from 1874 and compared it to the modern satellite images of Fairground Park. The old stables ran along the northeast boundary of the park where a modern paved road is today. The old map shows there were 601 cattle and horse stalls at the Fair Grounds, and really, Aristides could have lived in any of them. Even if horse bones ever turned up at the park, unless Aristides was buried with an identifier of some sort, there’d be no way to prove it was him.

Still tugging at threads, I reached out to NiNi Harris, who’s written a history book on St. Louis parks, to see if she’d ever heard of a horse graveyard on the old jockey club grounds.

“What an unusual request,” she said, laughing, over the phone. “My husband isn’t going to believe this.”

Even so, she humored my questions. There had once been a human cemetery not far from the park, but that had been moved. The cholera outbreak in the mid-19th century changed how people thought about burial practices, she explained. Doctors of that era didn’t know how the disease spread, and there was concern about contaminated bodies in small church graveyards. That fear was likely still lingering when Aristides died in 1893.

“I just don’t know where the animals were buried, and frankly, I hadn’t thought about it because it was such an issue with people cemeteries alone,” Harris told me. “I don’t have a clue.”

She had more of a clue than even she realized.

As our conversation continued, she told me she’d read all the available annual reports of the St. Louis park system. The earliest records go back to the late 1870s, and outline what happened in each park.

“I never found a reference to burying any animals in any of them,” she told me.

Suddenly searching for unidentifiable horse bones where those 601 stalls once stood made even less sense than it did before.

What happened to the first Kentucky Derby winner?

I turned my attention back to the modern satellite images and that hyperbolic newspaper clipping. Assuming that line about the glue factory was a joke, I wondered where a carriage possibly could have taken Aristides. Rationally, he’d have to be in St. Louis somewhere. Dead animals decompose and the summertime heat would have made any journey uncomfortable.

I zoomed out from Fairground Park and my eyes landed two miles to the northwest at Bellefontaine Cemetery and Arboretum. The cemetery is celebrating its 175th anniversary this year, oddly enough, it has at least one tie to the Kentucky Derby, Joe Shields, Bellefontaine's director of development told me.

Kentucky Derby founder Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr.'s family has a large plot there. His grandfather, the famed General William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery, rests a reasonable carriage ride from where the first Kentucky Derby winner took his last breath.

Shields assured me Aristides wasn’t with the Clarks, but he didn’t think my theory was completely off base.

“I am not 100% sure he is with us, but I am not discounting it entirely,” he wrote in an email. “I’m the fifth generation of my family to work at Bellefontaine, and I’ve heard many stories of animals being interred on a family lot.”

At least one of those stories involved a horse, he told me. Shields graciously connected me with Daniel Fuller, the cemetery chronicler, who went looking through the cemetery's work orders and financial records. His reply came three days before this column’s deadline and 25 days until the 150th Kentucky Derby.

“I looked high and low in work orders and Day Journals … and found no unusual activity,” he wrote. “Sorry I couldn’t be more help.”

After months of calls, emails, archive searches, and many other rabbit holes that didn't make the cut for this story ― I finally felt like my last thread had run out.

“This may be a mystery that's never solved,” Whitehead told me. “But it's interesting nonetheless and a good testament to his memory that we're at least trying to find him.”

I think she's right because one of the most telling things I learned about Aristides didn’t come from my research on him or the St. Louis Jockey Club.

I found it in the history of Churchill Downs.

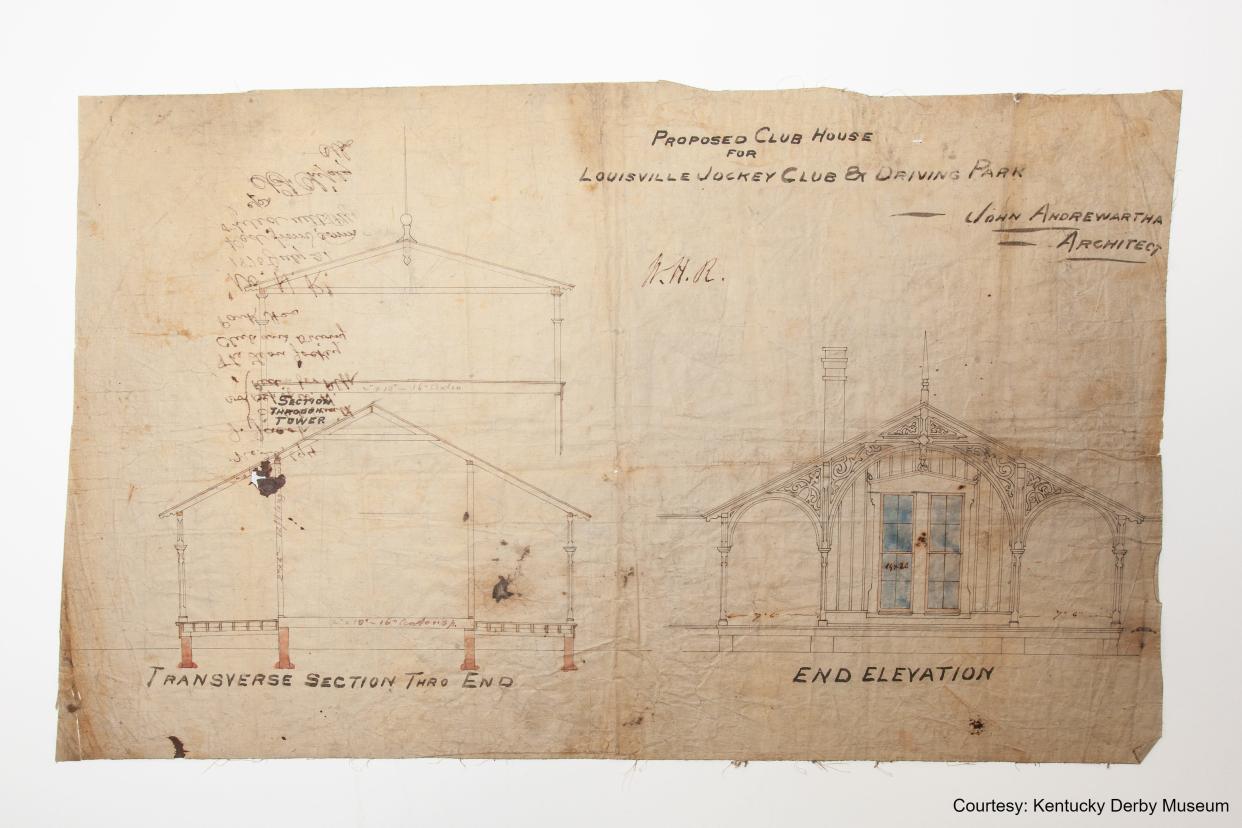

Louisville Jockey Club, which is the precursor to Churchill Downs, was teetering toward bankruptcy in 1893. As Aristides was dying, so was the race and the racetrack that made him a legend. He became the first winner of a race that was about to cease to exist.

If a new group, known as the New Louisville Jockey Club, hadn’t bought the track and made the changes that set the course for its success, the Kentucky Derby could be a long-forgotten fragment of Louisville history instead of the international sensation it is today.

“Secretariat is buried with great honor,” Whitehead told me. “That certainly wouldn't have happened for a horse, who had fallen from grace ... it’s hard to say what would have happened to him at that point.”

No matter how many threads we pull at looking for Aristides that’s likely the answer ― it’s hard to say.

But I wish whoever wrote that “good old-fashioned newspaper hyperbole” could see what Aristides' memory and the Kentucky Derby have grown into today.

The joke, I think, would be on them.

Aristides' remains have been lost to time, but his legend has lived on for nearly 150 years.

Features columnist Maggie Menderski writes about what makes Louisville, Southern Indiana and Kentucky unique, wonderful, and occasionally, a little weird. If you've got something in your family, your town or even your closet that fits that description — she wants to hear from you. Say hello at mmenderski@courier-journal.com or 502-582-4053. Follow along on Instagram @MaggieMenderski.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Where is the first Kentucky Derby winner Aristides buried?