Beloved Holy Cross Prof. Thomas Doughton who worked on Worcester’s Black History Trail died

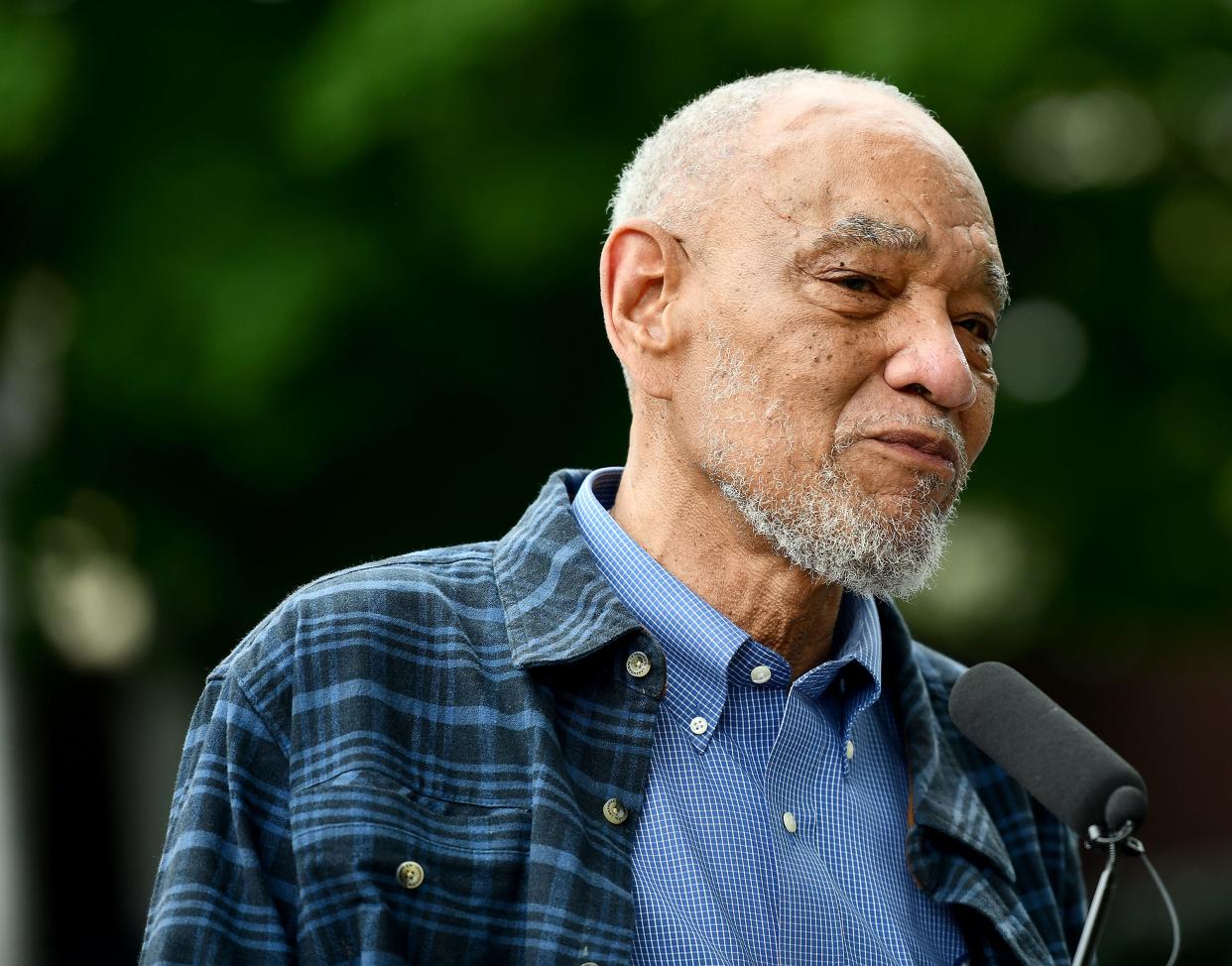

WORCESTER — The beloved and well-respected academic who created historical markers and digital materials for Worcester’s “Black History Trail” has died.Thomas L. Doughton, senior lecturer, Center for Interdisciplinary and Special Studies at the College of the Holy Cross, died Saturday at his home in Worcester.

In a joint statement released Sunday from the college, Vincent D. Rougeau, president, Elliott Visconsi, provost and dean of the college, Michele Murray, senior vice president for student development and mission, and Marybeth Kearns-Barrett, director, office of the college chaplains, confirmed Doughton’s passing.

Professor Doughton taught at Holy Cross for more than 20 years, with expertise in the Holocaust, comparative genocide, Native American studies and African American history. He was also highly regarded for his mentorship and unwavering support for students.

A well-respected educator and advocate for the local history and cultures of Black and Indigenous people in Worcester County and across Massachusetts, Doughton worked on Worcester’s Black History Trail, which documents and highlights historical sites important to understanding the experience of people of color in Worcester from the colonial period through the present, and worked actively and collaboratively on the Laurel Clayton Project, uncovering the history of a Black community in Worcester.

Paul F. Bailey is a co-founder of the Laurel Clayton Project. The project consists of homecomings that began in 1991 for former residents of the Laurel/Clayton neighborhood, which was erased by the construction of Interstate 290 and Plumley Village. He was shocked to hear the news that Doughton, his longtime friend, had died.

“Tommy was a very bright and great person,” Bailey said. “He was always committed to doing some good things for the Black community in Worcester, a lifelong resident of Worcester, always speaking of good things for the people of Worcester.”

Bailey, who knew Doughton all his life, praised Doughton’s efforts of bringing the richness of Worcester’s Black history to light.

“We had a neighborhood that was, kind of, taken away years ago, in respect to redevelopment…Tommy had always been involved (in the Laurel Clayton Project) and he always had great ideas. And bringing Holy Cross into the picture certainly helped us,” Bailey said. “Tommy was very helpful to donate to the cause. He would go wherever he could go to get support. And he did a lot of work, a lot of work.”

Bailey said he’s going to miss Doughton’s style, attitude, humor and warmth most of all.

Highlighting the city’s once close-knit bustling Black neighborhoods, the Worcester Black History Trail is a joint project of the Worcester NAACP branch, Worcester’s Laurel Project, the College of the Holy Cross and the office of former City Manager Edward M. Augustus Jr.

The trail consists of informational panels at various locations in the city and a series of medallions embedded in city sidewalks connected to a website, with an app allowing self-directed visits to African American historical sites in Worcester.

Doughton put the mechanical part of the project together last year with some of his students.

"It was important for me to do, first, because I am a historian and it needed to be done," Doughton was quoted as saying to the Worcester Telegram & Gazette in a July 2, 2019 article. “All over New England at the moment we are rethinking the role of people of color in history. But also, many of our seniors in Worcester between the ages of 80 and 100 are passing away. They have been custodians of information that doesn't really exist except within the community's knowledge."

Doughton said that in addition to the Laurel Clayton neighborhood, there were once several Black enclaves, African American residential areas, in Worcester. The oldest was at the end of Summer Street and Washington Square and adjoining East Worcester Street. Another was in the Exchange Street area in the 1840s. There was also the North Ashland Street area neighborhood. Another cluster was between Mason Street and Beaver Brook on the West Side of Worcester.

Doughton is among African Americans who can trace their ancestry in the Worcester area back to the 1700s.

Thomas Hazard, the great-great-great-great grandfather of Doughton, was a soldier of the Revolutionary War. Several other ancestors were part of the prestigious 54th Regiment, the first Black Northern regiment to serve in the Civil War.

Members of Doughton's family lived in Worcester's earliest Black communities on the East and West sides. One of those communities was in the Summer Street area near the rotary across from Union Station. That community no longer exists; the land was taken for construction of Interstate 290.

Another was near John Street Baptist Church, which was founded in 1886 by former slaves.

There was also the Beaver Brook section of Worcester in the greater Mason Court and Mason, Winfield, Abbott, Bluff, Bancroft, Bellevue, Dewey, Lovell, Parker, Pemberton and Pembroke streets area.

"When people think of Black Worcester they think of the East Side, but there was a substantial community on the West Side," Doughton told the Worcester Telegram & Gazette Feb. 19, 2012. "What makes Mason Court interesting is that Mason Court and the two buildings at the end of the court on Mason Street becomes the anchor from which an entire African American neighborhood is going to exist in Worcester. By 1950, there were several hundred African Americans living within a quarter of a mile from Mason Court. That little area now really doesn't look much like a neighborhood, but it actually was."

Doughton — who identified as a citizen of the Nipmuc Nation and had written significantly about the Native American presence in Southern New England — also spoke out about Native sports mascots.

“The question of Native mascots presupposes a whole cluster of associated questions that people don’t want to ask at the moment,” Doughton said. “How has this become a compelling issue for white Americans, and a compelling issue for white Americans who seem not to realize that Indigenous people on the great reservations of the West are living like they are people in Third World nations...To whom does it make a difference what the teams at Grafton High call themselves? Who is concerned about that? I have relatives who graduated from there — relatives of Nipmuc heritage — I’m not aware of any time that people who attended Grafton High School, played on teams, and of Nipmuc heritage were injured, harmed or offended by a mascot...Are we saying we have such an ill sense of who we are that your advertising defines us for ourselves? That’s a pretty condescending attitude.”

Doughton said the mascot debate sparked questions about the erasure of Native identity, adding that Native peoples also bear some responsibility for this.

“I think, to a certain degree, Native people also share some responsibility for perpetuation of Indian stereotypes, particularly in response to the national Pan Indian movement embraced by most Natives in the 1920s, especially people east of the Mississippi including New England Indians. Pan Indianism promoted unity and argued for an Indian-ness or shared Indian consciousness regardless of tribal or local affiliation as more and more Native peoples presented themselves in line with white expectations of what Indian should be.”

Local activist William S. Coleman said Doughton’s passing is a big loss for the city of Worcester.

“Tom Doughton was a historical treasure for the city of Worcester,” Coleman said. “He elevated people’s sense of purpose, not only for the African American community, but for the Nipmuc community.”

At the Worcester Black History Trail’s dedication ceremony, Doughton commented on the trail's significance.

“Until recently, the narrative (in Worcester) excluded marginalized populations. It only included Indigenous peoples. Other people of color were footnotes," Doughton said during the June 3, 2022, dedication ceremony. “This (Black) history, not even all people of color in Worcester know about it.”

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Beloved Holy Cross Prof. Thomas Doughton died at his Worcester home