'We belong here': Marquette professor documents 100+ years of Wisconsin's Latino history in new book

When Sergio González visited the Milwaukee County Historical Society for the first time 12 years ago, he expected to spend hours tracing his family's history through boxes and boxes of Wisconsin’s Latino history. After all, the Milwaukee County Historical Society has collected over a million photos and documents since it was established in 1935.

Instead, the archivist dropped off just three boxes for González to sort through.

“I was crestfallen,” González writes in his new book. “Three boxes: this was all the archivists had preserved on my community?”

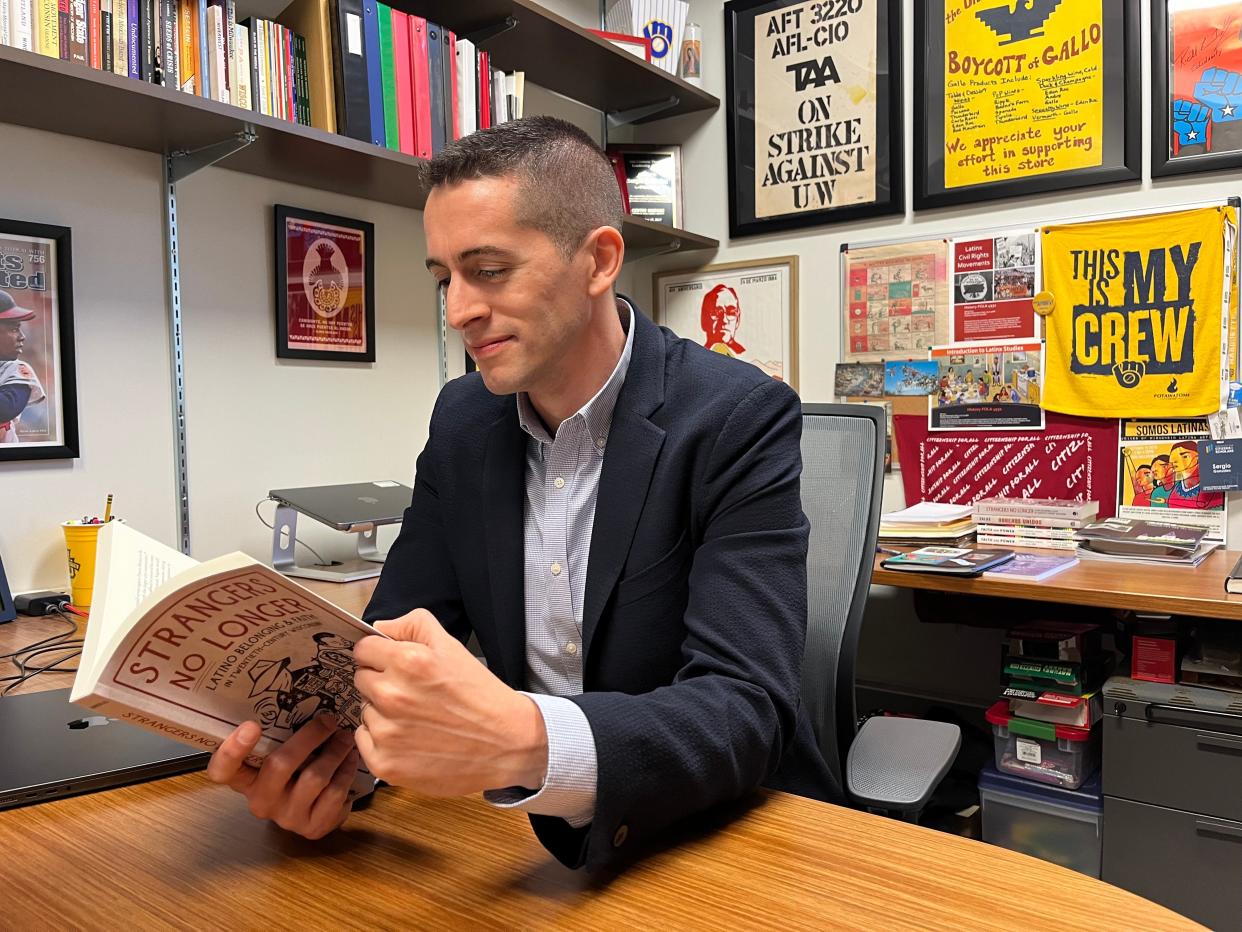

The book, “Strangers No Longer: Latino Belonging and Faith in Twentieth-Century Wisconsin,” is González's attempt to place the Latino community's extensive history on Wisconsin's center stage. Released last month, is the first book to compile more than 100 years of Latino history in the state.

González, an assistant professor of history at Marquette University, has long centered Latino experiences in his research. He published his first book, "Mexicans in Wisconsin," in 2017.

More: 'Mexicans in Wisconsin' tells a sweeping story of hardship and success stretching 130 years

Like many of his Latino students at Marquette, González struggled with his sense of belonging in Milwaukee. He didn't learn about Latino history in grade school. After his parents, who are both from Jalisco, Mexico, moved the family from Milwaukee to Brookfield, González saw fewer families that looked like his.

It wasn’t until he studied Spanish, history and secondary education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison that he began to learn about the extensive history of Latinos in the Midwest.

His experience at the Milwaukee County Historical Society was a stark reminder that Wisconsin's Latino history isn't well known.

This discovery, though initially disheartening, inspired González to take his research a step further. Rather than piecing together just his own family's history in the state, González spent 10 years documenting a comprehensive history of Latinos in Wisconsin.

"In many ways, the stories I'm telling in this book are the stories of my family, of me, the people that I love and grew up with here in the Milwaukee area," González said.

Latinos have lived in Wisconsin since at least the 1880s

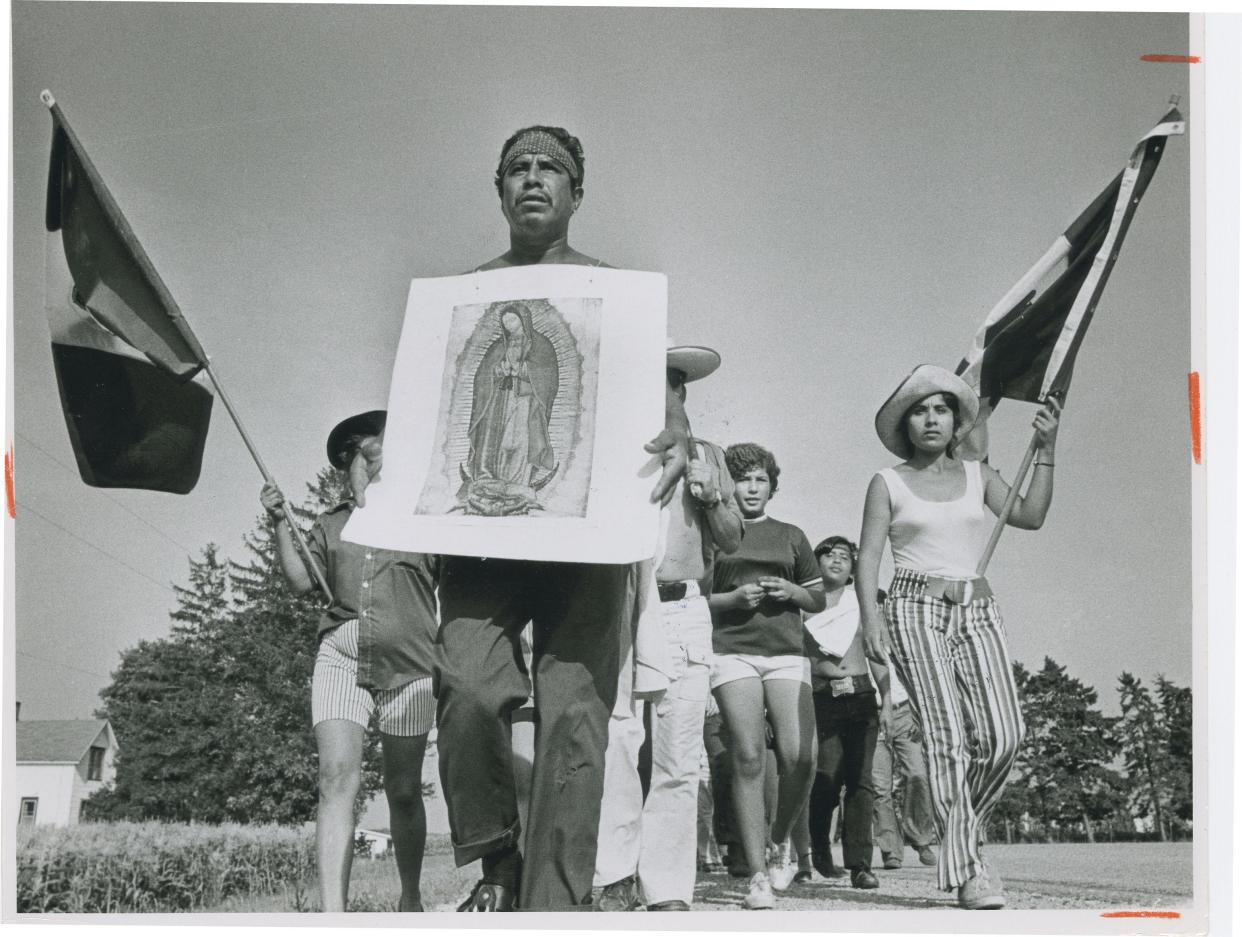

While simultaneously telling the story of how people from Latin America and the Caribbean found their way to Wisconsin, González's new book shows how local and federal government policies presented the long-lasting narrative that Latinos were just temporary visitors to the U.S.

For example, the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, the first U.S. law limiting immigration from certain countries, made an exception for Mexican immigrants for temporary agricultural work. They were expected to briefly work in the state and go back to their respective countries, not settle down, according to González.

Despite Latinos living in Wisconsin since the at least the 1880s — only 32 years after the state was founded — they have been routinely cast as Wisconsin's newest immigrants, he said.

"Even though they haven't been as large as other minority communities, most importantly Black Wisconsinites, they've still been here," González said. "They've been present not just in Milwaukee, Madison, or Green Bay, but they've been present all across the state of Wisconsin — urban, rural, small town, big town areas."

For example, in the 1930s, Wisconsin annually recruited 3,000 Tejanos — Mexican people who lived in Texas before it became a state — to work in the sugar beet industry. By the summer of 1947, Tejano migrants worked in 23 of Wisconsin's 71 counties harvesting cucumbers, cherries and sweet corn. These workers and their families, along with workers hired from Belize, the Bahamas and Jamaica, spent spring to summer in areas like Wautoma, Waupun and Door County until sometime after World War II, González said.

Their labor caused a 42% increase in Wisconsin's farm production, according to "Strangers No Longer."

"People would see them as just migrants," González said. "Aliens who are just coming in and out of their spaces. But they left whispers of their permanence in many different ways."

Today, Latino immigrants are the labor force behind Wisconsin's dairy industry, which contributes $104.8 billion annually to the state. That's just one way Latinos contribute to Wisconsin's economy, González said.

"For us to understand where the region is gonna go for the next 20 or 30 years, it behooves us to understand where we've been for the last 100 years," González said.

Wisconsin could do more to preserve Latino history

Recently, González began working with the Wisconsin Historical Society as a public historian for the new Wisconsin Historic Center in Madison, which opens in 2026. He'll be weaving Latino history throughout the museum's three galleries.

Texas, Arizona and California have done a better job of preserving what migrant life in their states looked like than Wisconsin, González said.

Historic markers in Texas show where Latino migrant workers set up camps in Lubbock County while working on the railroad. The California Migration Museum offers self-guided audio tours that trace the footsteps of Mexican migrants in Los Angeles in the 1930s and El Salvadoran asylum seekers during the 1980s Sanctuary movement in San Francisco.

But the National Register of Historic Places doesn't have a single building acknowledging Latino settlement in Wisconsin, González said.

González now sits on the Wisconsin Historic Preservation Review Board and hopes to change that. He blames this issue on past archivists not valuing Latino history, but also on the fact that many places where Latinos lived and worked in Milwaukee were destroyed by highway construction in the 1940s and 1950s.

"That means that we have to catch up and do that work here, too," González said.

However, the duty to preserve historic places doesn't just fall on the shoulders of historians, he said. Members of the community can petition the National Register of Historic Places to recognize historic sites in the state, too.

"My hope is that we put these stories out there, people start asking questions, do their own research, and they put the applications together to make it happen," González said.

Wisconsin churches were crucial meeting places for Latinos

"Strangers No Longer" also follows the role Wisconsin churches played in Latino history.

According to González, the churches, at times, were a tool to Americanize Latinos. At other times, churches acted as meeting places to gather political support for the Latino community.

González grew up in church and saw it as a central hub for immigration and labor activism. But the role churches play in Latino history is often excluded by Latino historians, González said, because churches didn't always side with Latino activists.

"Regardless of what your political orientation or your own faith beliefs are, the church is really important for understanding Latino communities," González said.

One historical moment the book discusses is the 1980s Sanctuary movement, a religious and political campaign to house refugees escaping war in Central America. Catholic churches, like St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Church in Milwaukee's south side, sheltered and protected the identities of undocumented asylum seekers from El Salvador and Guatemala. As a result, former Wisconsin Gov. Anthony Earl declared the state a sanctuary for refugees in 1986.

Wisconsin churches have broken federal law to shelter undocumented immigrants several times since, González said. His next book will be an edited volume of the Sanctuary movement.

"Again, that's part of this history that I don't think many Wisconsinites are familiar with," González said.

Because "Strangers No Longer" is an academic text, González acknowledges it is not necessarily geared toward middle school and high school readers. But the book could be a great read for educators in Wisconsin and the Midwest who want to incorporate Latino history into lesson plans, he said.

According to González, teaching youth about Wisconsin's expansive Latino history can improve their sense of belonging.

"I think it's important for us to claim this space as ours, not because we have any ownership over it, but because it allows us to really feel like we belong here," he said.

Gina Castro is a Public Investigator reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. She can be reached at gcastro@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Marquette University professor Sergio González documents Wisconsin's Latino history in new book