He begged for help, didn’t get it and took his own life. How the NYC criminal justice system let down Michael Nieves

Ten weeks to the day before a Harlem-born inventor died after slitting his throat in a Rikers Island jail cell, he stood before a Manhattan judge to make a desperate plea.

Michael Nieves had been waiting for trial for three years, circling eight times through worn-out revolving doors between the city’s jails and psychiatric facilities. He’d twice been found unfit for prosecution. Medical records show he suffered from psychotic delusions and deep depression.

He knew he needed help.

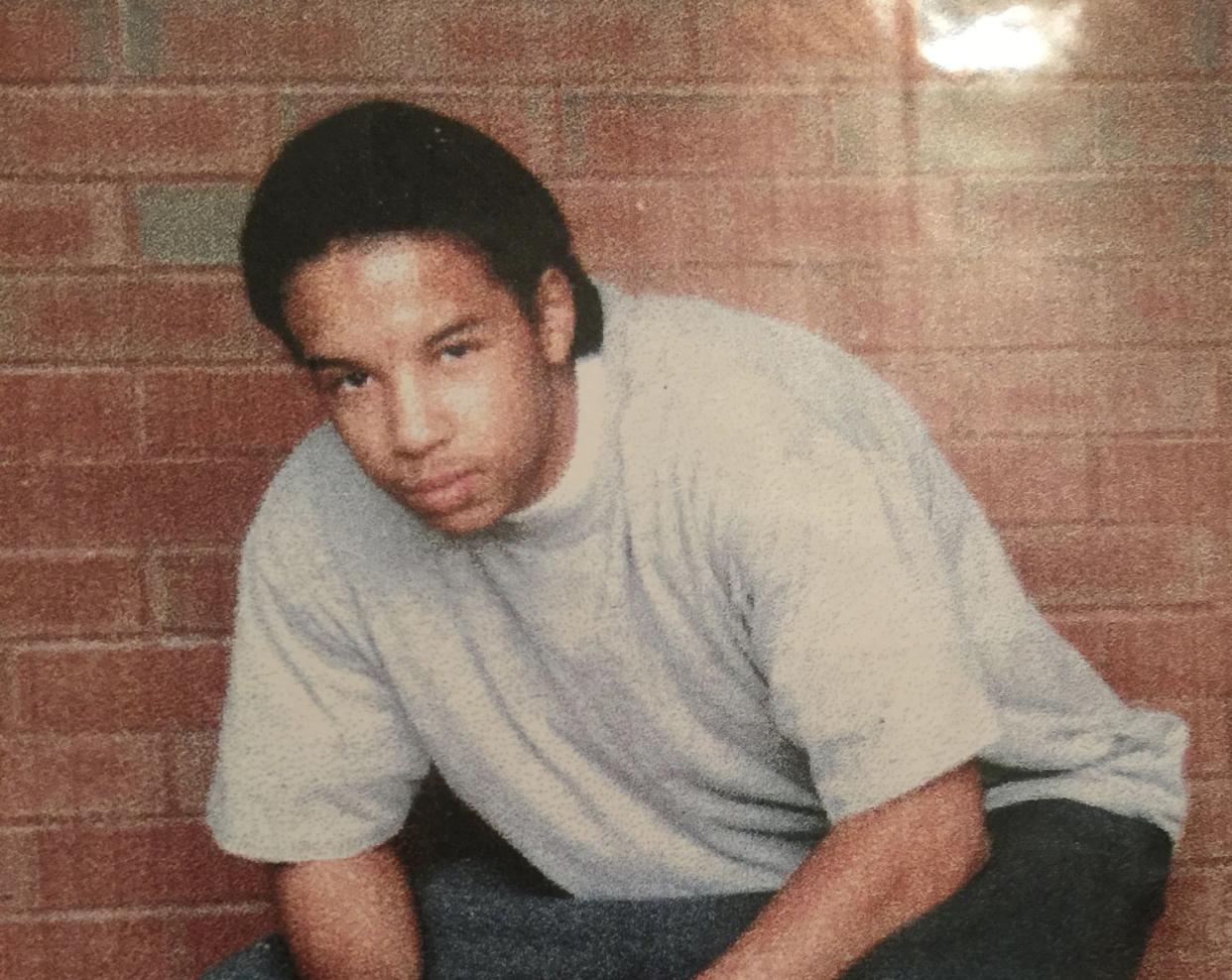

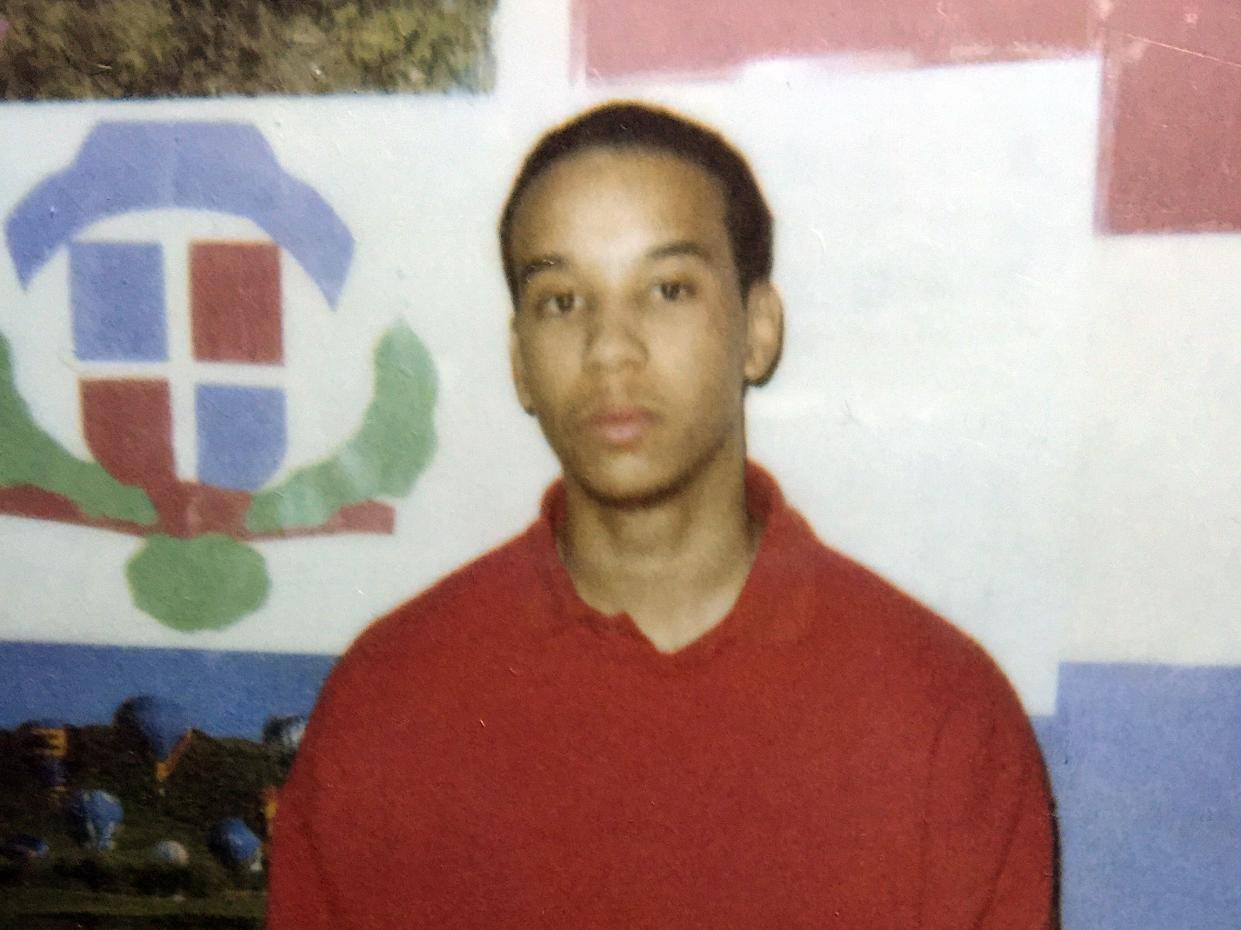

Harlem-born inventor Michael Nieves, who had long balanced his mental illness with intellectual brilliance, slit his throat in a Rikers Island jail cell.

“I was hoping you would consider referring this (case) to mental health section,” Nieves, 40, asked Judge Laura Ward on June 21.

But Ward told Nieves that the specialized court wouldn’t take his case because of a previous conviction for a violent offense.

“It’s not going to go to the mental health court,” the judge told him during the hearing. “I don’t have the power to do that at this point.”

By Aug. 30, Nieves was dead. He sliced his throat with a Department of Correction-issued razor, which staff failed to retrieve from him in violation of agency policy. Three officers who looked on were suspended after his death.

“What’s particularly disturbing is the indisputable fact is that the department and the city were on notice because they were well aware of his mental health history,” said Jonathan Abady, a lawyer representing Nieves’ surviving brothers. “He was a sort of screaming neon sign for mental health assistance, and what he got instead was this inexplicable callousness of people watching him while he died.”

The circumstances surrounding Nieves’ suicide are dramatic, but not unique. They illustrate a profound weakness in the city’s criminal justice system when it comes to handling people with psychiatric disorders — and the devastating consequences of that shortcoming.

“It’s infuriating that Michael battled severe mental illnesses for nearly 25 years, which was all documented by the courts, yet up until his last day, the courts played him like a yo-yo bouncing him between Bellevue Mental Health Ward and Rikers Island,” his brothers said in a joint statement.

Few solutions

The problem has become increasingly hard to ignore in New York City, where Mayor Adams’ office says half of the people in jails and prisons had diagnosed mental health needs in the last fiscal year. With those numbers, the demand for specialized proceedings and services far exceeds what’s available.

The solution Nieves unsuccessfully sought had the potential to be an effective one. First established in New York in 2002, the specialized court aimed to connect people with mental health issues facing criminal charges with services. Defendants gain access to housing, intensive mental health support in their communities, and a team of professionals to aid in their continued care.

But only the lucky and limited few succeed in having their case heard there. Public defenders and other criminal court administrators who spoke with the Daily News said the specialized court has multiple barriers to entry — including a cap on admissions.

Jeffrey Berman, a mental health attorney in the Manhattan Legal Aid Society’s criminal practice, said succeeding in getting a case heard by a mental health judge is like “winning the lottery.”

District attorneys are the ultimate gatekeepers when it comes to getting a case transferred, but a detainee needs the court’s support as well. Administrators said they don’t consider people like Nieves a good candidate because community programs are not set up to treat people with severe mental health needs.

“Diversion and mental health courts are not meant for defendants who displayed the behavior and had the problems that this individual clearly suffered from,” said Office of Court Administration spokesman Lucian Chalfen.

Berman said that’s a narrow interpretation — and the system should be expanded to accommodate more people with psychiatric problems. He pointed to a bill currently before the state Legislature that would do just that.

The alternative is often Rikers Island and other city jails, where detainees living in overcrowded conditions and a violent atmosphere can go months without receiving psychiatric medication, according to complaints documented by Legal Aid.

Riker’s Island as seen from the Bronx on Sunday September 11, 2022. (Theodore Parisienne/)

“At the end of the day, no unit on Rikers can respond appropriately to severe mental illness,” said Julia Solomons, a social worker at Bronx Defenders. “The jails do not have the resources or the capacity to provide the support that people with these chronic and severe mental health conditions need.”

While on Rikers, Nieves spent time at the PACE unit, an acronym for Program to Accelerate Clinical Effectiveness. It was at the Anna M. Kross Center where he slit his throat with the razor he signed out from staff that they failed to take back.

A revolving door

Nieves’ dizzying three-year ordeal from arrest to suicide began in March 2019, when authorities say he broke into an apartment and barricaded himself inside a bedroom with a terrified tenant.

During the alleged encounter, Nieves put a dresser to the door to prevent the woman’s husband from entering and started trying to light things on fire. He then locked himself in the bathroom. Nobody was hurt during the episode except Nieves, who suffered burn wounds. The NYPD and FDNY marshals brought him to Harlem Hospital.

After a month, he was released to an outpatient facility and almost immediately arrested on burglary and arson charges for the bathroom incident. At his first court appearance, a judge sent him to Rikers.

It was the beginning of Nieves’ revolving door. Each time his condition started to improve he’d go to jail. Then he’d be sent back to psychiatric facilities when he deteriorated in lockup.

In October 2019, Nieves was ruled unfit for prosecution by Manhattan Judge Curtis Farber following the results of a psychiatric exam and sent to a state health facility. In May 2020, Judge Erika Edwards found him fit for prosecution. In November 2021, Judge Laura Ward agreed he was still fit for prosecution. In March of this year, following a 730 exam, which determines mental health, Judge Ward ruled he was again unfit for prosecution.

And then in June, when he asked for his case to be moved to mental health court, Ward found him fit again, sending him back to Rikers. She ordered a new psychiatric exam at Nieves’ last court appearance on Aug. 1.

It wasn’t clear whether he received it before his death a few weeks later.

Genius — and illness

The middle child of three, Nieves was born in 1982 at Harlem Hospital. His church-going single mom raised him with his two brothers, Anthony and David, in a Lower East Side public housing development.

Somewhat on the chubby side as a child, Michael took up boxing to defend himself against neighborhood bullies and developed a lean, muscled frame, his brothers said. He attended A. Philip Randolph High School by St. Nicholas Park, where his brothers said he “easily” received straight As.

Michael Nieves is pictured as a child in an undated photo. Harlem-born inventor Michael Nieves, who had long balanced his mental illness with intellectual brilliance, slit his throat in a Rikers Island jail cell.

“While growing up with my brother Michael, David and I noticed how brilliant and good-hearted Michael was. Although Michael exhibited early signs of mental illness, he also exhibited signs of sheer genius,” his brother Anthony Morgan told the Daily News via email.

Nieves was an inventor. His brother shared with The News scores of ideas for inventions and intellectual property patents that he mailed to them from correctional facilities, some of which he had notarized behind bars.

In 2019 and 2020 alone, Nieves proposed — among many others — a blanket or beach towel with a built-in cooling device; a kitchen faucet-based juice maker, a vacuum cleaner for insects; and a program that would convert technical or legal language into prose the average teenager could understand.

“Anthony and I were amazed at the fact that Michael is someone who was institutionalized — always in a correctional facility or mental hospital — yet he was able conjure ideas for products/services that he had no access to,” David Nieves said.

Nieves’ brothers wrote that they want to post Michael’s ideas online for anyone to try to make into reality as the ultimate legacy of a tragic life cut too short.

“The point is that Michael was not a hard-boiled criminal with no hope who was a drain on taxpayers; Michael wanted to contribute to the world.”

At the same time, Michael’s illness emerged in earnest, first manifesting in his sophomore and junior years. They said he first went through the revolving door between jail and psych facilities at 16 or 17, splitting time between Rikers and neighboring Kirby Forensic Psychiatric Center.

An undated photo shows Michael Nieves as a child with his two brothers, Anthony Nieves Morgan and David Nieves. Harlem-born inventor Michael Nieves, who had long balanced his mental illness with intellectual brilliance, slit his throat in a Rikers Island jail cell.

Nieves served two stints in state prison, records show. The first was 2004 to 2005 for attempted weapons possession.

In 2009 he was convicted of robbery and attempted assault and sentenced to up to five years. He was paroled in two years, but was sent back three more times for minor parole violations and was finally released for good from that sentence in 2018.

Anthony, a software consultant, and David, who works in sales, expressed frustration at the courts’ short-sightedness when evaluating whether someone is fit for prosecution.

“This led to an increase in fighting and getting in trouble with the law, which was the start of the cycle of him going in and out of prisons, psychiatric hospitals, and men’s shelters that lasted up until his death,” his brothers said.

Death at Rikers

Nieves was the 13th detainee to die this year awaiting trial in the city’s jails. That number has since swelled to 16, matching the number who perished in all of 2021. The 32 deaths since Jan. 1, 2021, are by far the most in memory — and bring the enduring crisis in the jails into sharp relief.

Solomons said Nieves is just one of so many in custody suffering from mental illness who see their symptoms exacerbated behind bars, endangering themselves and society at large.

“Mental health advocates are not looking to perpetuate institutionalization because so much research shows people can be stabilized and given treatment in the communities,” she said.

Harlem-born inventor Michael Nieves, who had long balanced his mental illness with intellectual brilliance, slit his throat in a Rikers Island jail cell.

But with community services in short supply, the issue often ends up in the hands of the police.

Cops who spoke with The News said they don’t want to be the ones responsible for dealing with people experiencing mental health crises either. But they don’t feel like they have a choice under the current infrastructure.

“When you have a prisoner who is an [emotionally disturbed person], you are sitting on them for days because they are flipping out in the cells. You have to not only protect them, you have to keep an eye on them so that they don’t kill themselves,” said one NYPD sergeant who asked to remain anonymous so they could speak candidly.

“As a sergeant, we don’t have the manpower to process all these people.”

The sergeant said without systemic failures being addressed upstream, cops will continue to be the first point of contact for someone who breaks the law as a result of untreated mental illness.

“They should have mental health professionals assigned to these commands to deal with these people,” the sergeant said. “There’s a lot of good ideas, but no one wants to pay for them.”

At his appearance in June, Nieves apologized to the judge for accusations he’d levied against her in a detailed August 2021 federal lawsuit he mailed in via the Bellevue prison ward. Nieves wrote the legal papers himself, complete with citations and a detailed chronology of his own case.

“I know I might have seemed insulting or arrogant, and it wasn’t my intentions,” Nieves said. “It’s just that considering how long the case has been on for, almost three years now … I wasn’t in my right mind. I meant no disrespect at all.”

Nieves’ grieving brothers described it as tragic that their struggling sibling died even though the courts had decades’ of evidence he battled severe mental illness. His brothers said the red flags and suicidal tendencies were long apparent, like Nieves’ many scars of self-mutilation.

“He should never, never have been at Rikers with poorly trained, unsympathetic staff that seem to be no better than the inmates they’re responsible for caring for,” they said.