Before backlash, Detroit had love affair with disco, nightlife and Bee Gees’ hits

When Dave Fisher saw “Saturday Night Fever” back in the day, it transformed him.

“That movie changed everything for me,” said Fisher, who lives in Shelby Township.

“I practiced the dance moves in the mirror, bought the Angel flight pants and disco shirts and shoes, did my hair just like John Travolta. I tried to emulate his walk. I thought I was Travolta. We all thought we were.”

In his late teens, Fisher danced frequently. At Roma Hall on Gratiot in Macomb County. At East Warren Lanes in Detroit. At My Place and The Salt Mines and Sound Machine/Butterfly Suite.

“Dancing was a great way to meet girls,” he said.

Released in December 1977, “Saturday Night Fever” ruled the box office and spawned a Bee Gees-driven soundtrack that held the No. 1 Billboard spot for 24 straight weeks and launched a stream of massive hits.

An illuminated dance floor on the east side

Disco was not new, of course. It had emerged in the late 1960s at urban clubs frequented by African American, Hispanic and LGBTQ+ patrons. “Boogie Fever,” “The Hustle,” “Get Down Tonight,” “Love Machine,” “Jive Talkin’,” “Disco Lady” and “Car Wash” had already charted, as did a parade of Motown recordings ― Diana Ross’ “Love Hangover,” Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” and Thelma Houston’s “Don’t Leave Me This Way.”

But “Saturday Night Fever” supercharged the disco craze, taking it to a wider audience. Suddenly, hotels, banquet halls and bowling alleys throughout metro Detroit were refashioning their spaces into discotheques, adding mirrored balls, flashing lights, lasers, fog machines and enhanced, bass-friendly sound systems. Some had video projection and at least one offered a slide. There were balloon drops and bubble machines.

A DJ who knew how to spin could elevate a venue’s reputation.

Disco franchises like Grogshop and Uncle Sam’s debuted in the region.

Harpo’s, the old Harper Theater on Detroit’s east side, advertised the biggest dance floor. It was illuminated like the one Travolta commanded as Tony Manero. And it could pack a crowd of hundreds.

Everybody wanted in on the action. Established stars like Alice Cooper, Elton John, the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones all dallied with the genre.

Even 60-year-old Detroit Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell, a sometimes songwriter, collaborated on a disco song, “Surround Me,” recorded by Beverly and Duane.

Flashback: The fire-breathing preacher who captivated Detroit’s rich and poor in 1916

Le Freak, c’est chic

On weekends, popular discos saw customers lined up outside.

Lisa Jo Girodat, a student at Sterling Heights High, headed to the clubs with coworkers after her shift at Burger King — and after a change of outfits.

“Going there was about getting dressed up, dancing, the social aspect,” she said. “It had a huge impact on my taste in music and the clothes I wore.”

She picked up moves watching Dick Clark’s “American Bandstand.”

For others, inspiration came from “Soul Train,” Detroit’s “The Scene” and, beginning in January 1979, “Dance Fever,” with Deney Terrio.

Girodat loved moving to The Jacksons’ “Shake Your Body” and Chic’s “Le Freak.”

Disco was everywhere. On radio. On TV. On the big screen (check out Jeff Goldblum in “Thank God It’s Friday” or Rudy Ray Moore in “Disco Godfather”).

In metro Detroit high schools, teens practiced the Brooklyn Shuffle in gym class. Middle-age parents learned the moves at recreation centers and Arthur Murray Studios. There was disco for seniors, disco with Santa and disco roller skating.

Every discotheque had a different vibe.

Kimberly Sample Garrisi liked Carmen’s East, a disco-only establishment along Hoover in Warren. She went there nearly every weekend.

“It was a purely disco place,” she said. No connected bowling alleys or hotel lobbies.

It emphasized partner dancing, not freestyle, and had a raised dance floor.

“I had my disco dresses and heels. It was fabulous,” she said. “We were all young. You made friends. There was always a new influx of people.”

Muriel Boivin liked Club Polski on Conant in Hamtramck.

“True disco,” she noted. “Crystal ball, large dance floor. Very, very packed. I enjoyed the music and dancing. It was a great way to get together with my friends.”

There was a faddish element to disco. A lot of young people, like Greg Reasor, were just flowing with the times.

Reasor’s girlfriend loved to dance. After they saw “Saturday Night Fever” at the Troy Drive-In, the two hit the dance floor. “I bought a light blue suit for those few summer nights,” he said.

Flashback: How Detroit's Renaissance Center got its name

Disco haters counterattack

That fall, he returned to the Michigan State campus and found his friends listening to the Ramones and The Clash. Punk and New Wave had arrived. For Reasor, disco became history. (So did his relationship.)

As an exclamation point to his changing sentiment, Reasor delivered a “disco sucks” talk in speech class. He shattered a vinyl record for emphasis.

A backlash was underway.

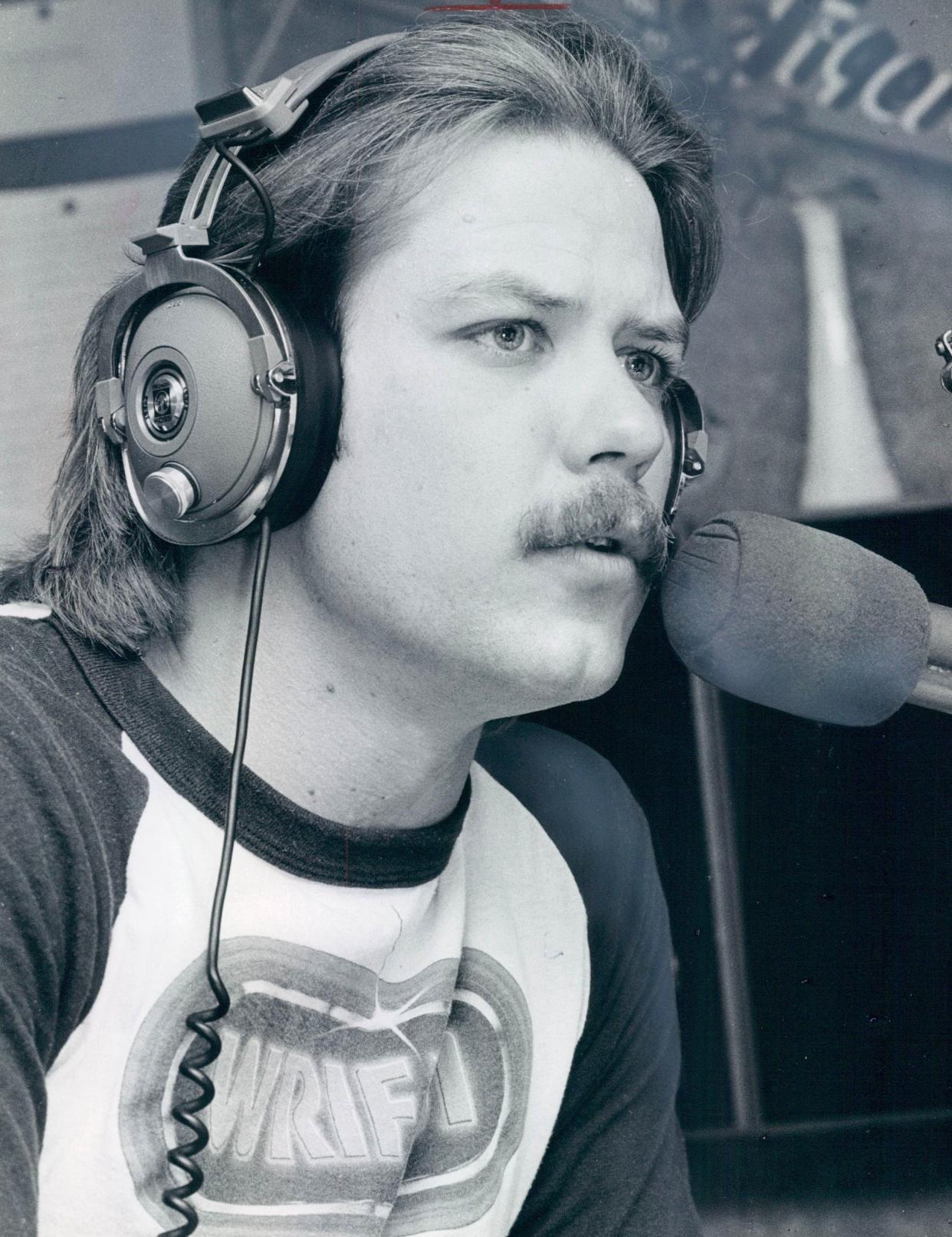

In the Detroit market, radio station WRIF-FM, with its black “home of rock and roll” T-shirts, launched D.R.E.A.D. ― Detroit Rockers Engaged in the Abolition of Disco. Promoted heavily by RIF staffers George Baier and J.J. Johnson, the campaign quickly attracted thousands of members. Michigan rock icon Bob Seger sang about old-time rock and roll, warning, “Don’t try to take me to a disco.”

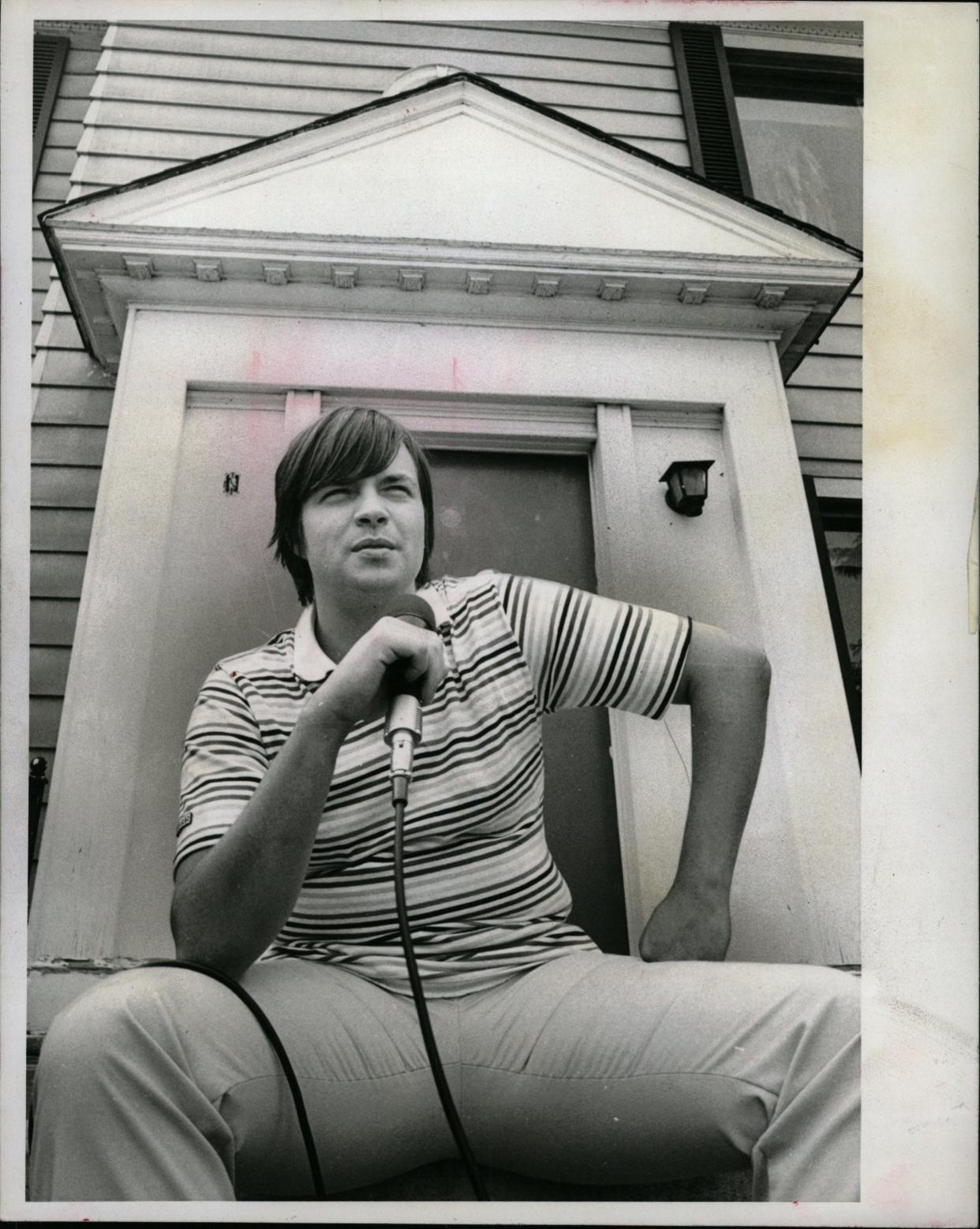

But it was a promotion at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979, that crystalized the movement.DJ Steve Dahl had made his name at WWWW-FM and WABX-FM in Detroit before being lured to Chicago. When listenership didn’t materialize there, the station converted from rock to disco. Dahl lost his job — sacrificed “on the altar of disco,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

Dahl, just 24, built a following at another station by trashing disco. He parodied Rod Stewart with “Da Ya Think I’m Disco” and rallied supporters to gimmicky protests, where some threw marshmallows (and worse) at disco fans.

“Disco music is a disease,” Dahl said.

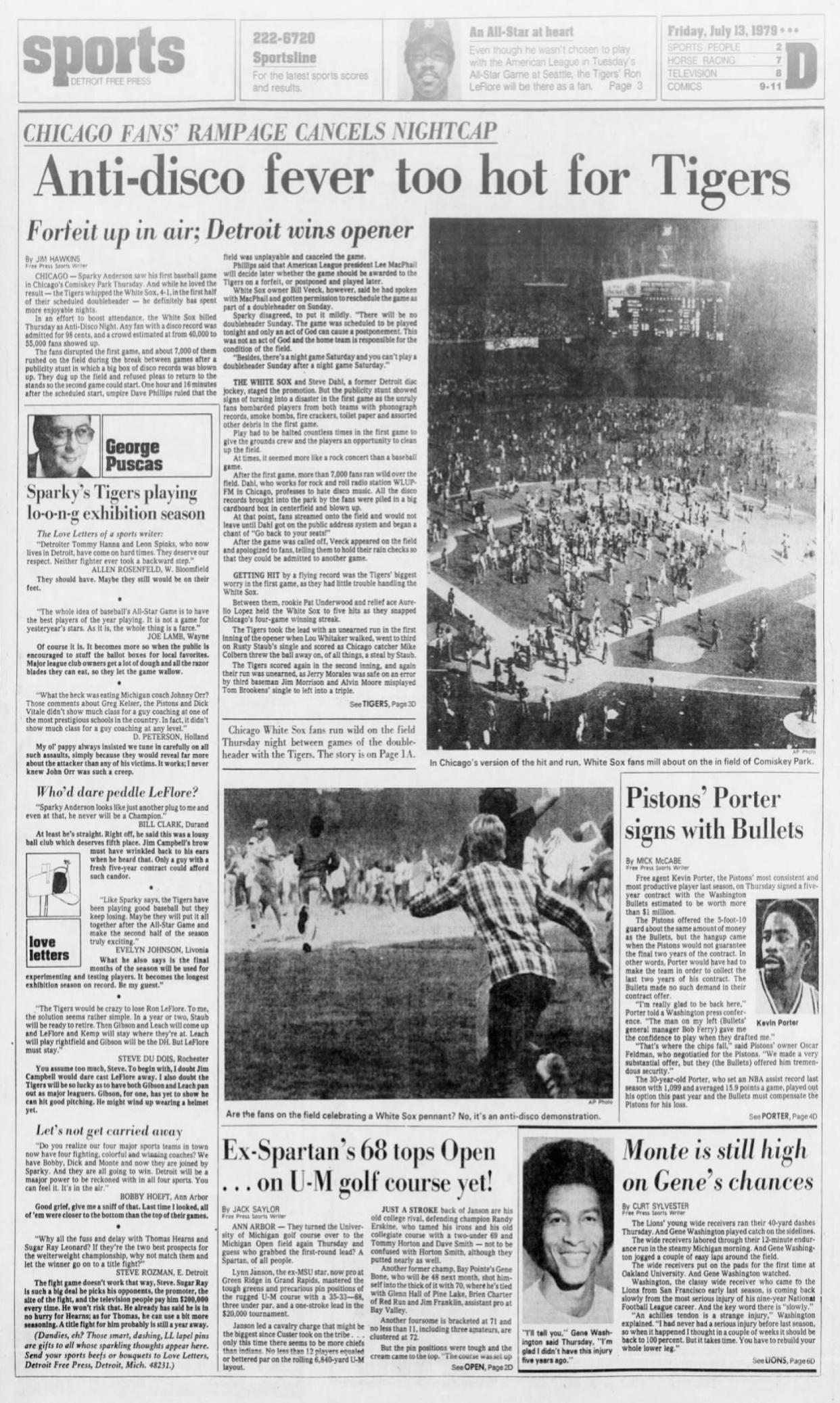

The Chicago White Sox, struggling to bolster attendance and owned by the celebrated promoter Bill Veeck, allowed Dahl to stage an event called “Disco Demolition Night.” Fans who brought disco records received admission for 98 cents. Comiskey Park sold out. Between games of a Sox-Tigers doubleheader, Dahl took the field in a jeep, wearing military gear. He led the masses chanting “Disco Sucks” and then detonated thousands of albums, sending shards of vinyl across the outfield.

The promotion devolved into chaos as thousands poured over barriers, vandalized facilities, set fires on the grass and refused to leave until police arrived.

Music historians cite the demonstration as a key moment in disco’s decline. Some academics also view the backlash in general as motivated partly by racism and homophobia, given disco’s roots.

The death of disco didn’t come instantly. A week later, Donna Summer reigned for five nights at packed Pine Knob.

Ten days after, the Bee Gees shook the Pontiac Silverdome.

No band was more tainted by the backlash than the Bee Gees. Their successes stretched backed to the Beatles era, but they struggled to escape their white-suit, gold-chain image. They became a punchline. In America, their sales tumbled drastically after 1980, and they didn’t tour the states again until 1989.

When they finally visited Pine Knob that August, I was among the curious thousands in attendance.

Near the concert’s zenith, the opening notes of “Stayin’ Alive” reverberated through the pavilion. Instantly, the air turned electric and the crowd bolted to their feet. With lights pulsating, fans danced feverishly at their seats and spilled into the aisles. For a moment, it was 1978.

As the song finished, Barry Gibb cast a teasing smile at the audience and said, “I thought you hated disco.”

Tom Stanton is author of several nonfiction books, including the Tiger Stadium memoir, “The Final Season.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit music history: Disco fever — and backlash — hit Detroit hard