'Austin has done almost nothing': Time to thank the Tonkawa for saving the capital of Texas

Envision Texas without Austin.

Jokes aside, our state would be a different place, right?

Yet it almost happened.

In March 1842, just three years after the city was founded, President Sam Houston declared martial law and ordered that all families in the Austin vicinity, an area vulnerable to Comanche or Mexican attacks, to "leave as soon as possible for a safer section of the country." During the next three months, Austin population dropped from approximately 800 to 200.

Houston subsequently convened the Republic of Texas Congress farther east at Washington-on-the-Brazos, and sent the militia to seize the fledgling nation's archives from Austin.

His gambit failed.

One hero from that episode is fairly well remembered: Innkeeper Angelina Eberly fired a cannon in the dead of night to alert townspeople to the seizure. A posse caught up with Houston's militia at a fort north of Round Rock and returned the archives. Rightly, a statue of a furious Eberly stands at a prominent spot on Congress Avenue.

Where are monuments, however, to the other saviors of Austin from that period? While most of the settlers abandoned the city, their friends and allies, the Indigenous Tonkawa set up camp on Little Shoal Creek, just west of Republic Square Park, which protected the city's western flank from Comanche raids.

More: Who found that Treaty Oak was sick in 1989? Clue: She had view from her office window

While bolstering the city's population and trade for some two years, they interacted easily with the Texians who remained behind, as memoirs from that period attest.

Late last year the Tonkawa, who were forcibly expelled from Texas in the 1880s, 40 years after the Archives War, returned to reclaim a sacred spot, Red Mountain, in Milam County northeast of Austin. Although now based at a reservation in northern Oklahoma, they still strongly identify with their traditional homeland, and in fact are the only federally recognized tribe with an origin story in what is now Texas.

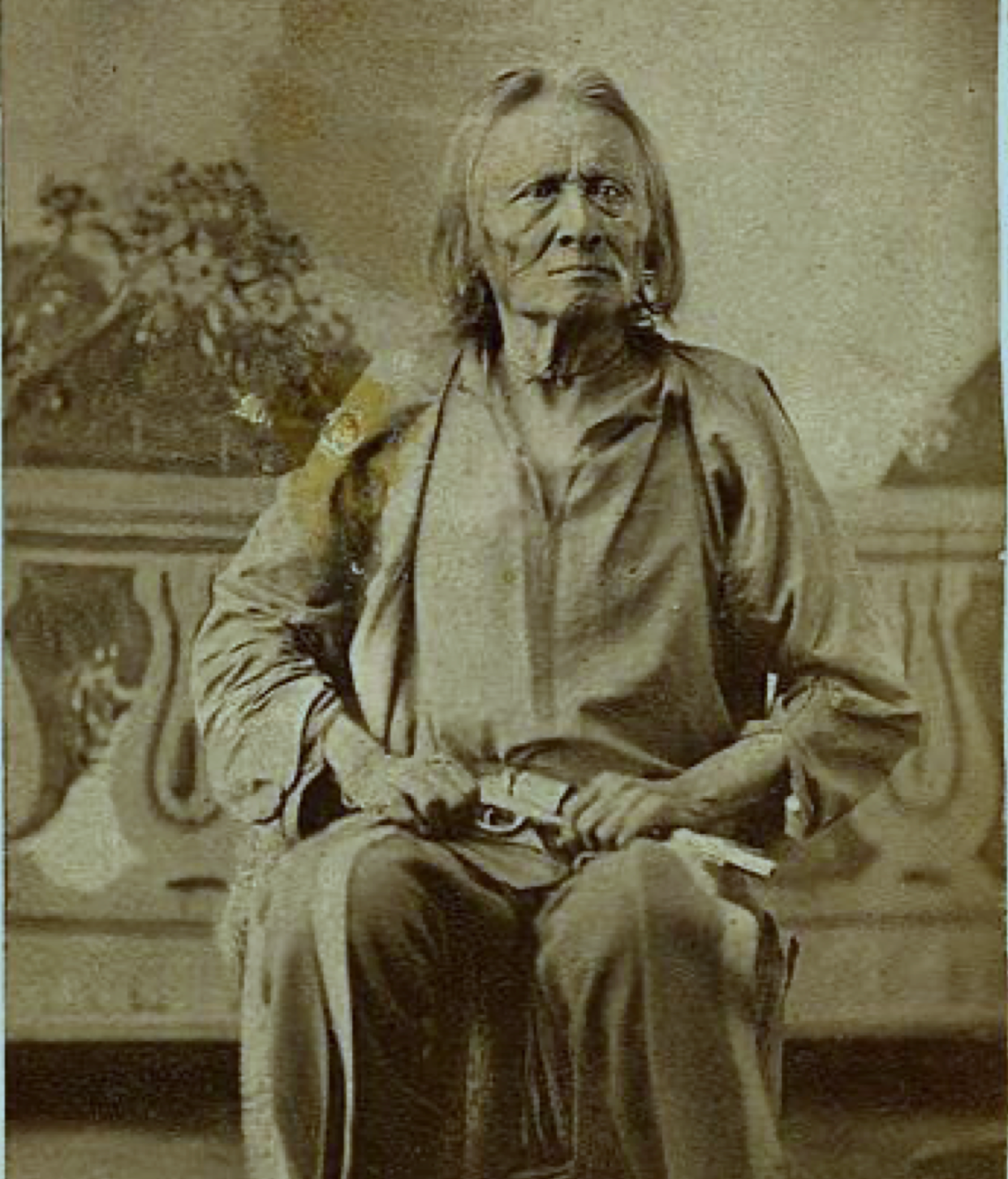

To honor the tribe, San Marcos has raised a heroic statue to Tonkawa Chief Placido by the San Marcos River. At Pioneer Farms in Northeast Austin, replica teepees have been placed at a confirmed Tonkawa campsite. Before that, in the 1940s, a neighborhood in North Austin named one of its streets Tonkawa Trail after the historic trail there along Shoal Creek, perhaps the only Tonkawa-named location in the city today.

Time is long overdue to honor these saviors of Austin openly and conspicuously.

Tracing the Tonkawa history here

The story of the Tonkawa's short residence in the city during 1842 and 1843 is told in a carefully resourced paper, "How the Tonkawa Tribe Came to Live in Austin," placed at the Austin History Center on Aug. 2, 2023. It was written by Bob O'Dell, producer of the upcoming documentary film "Tonkawa: They All Stay Together," due out later this year.

Herewith are 10 highlights from that research paper:

'The Land of Good Water'

While historically the Tonkawa hunted and gathered along both sides of the Balcones Fault from Oklahoma to Mexico, they considered the land between the Colorado and Brazos rivers their homeland, which they called "The Land of Good Water." "This was known as one of the most prolific deer habitats of all of North America," O'Dell writes. "Around 1800, the Tonkawa bargained with a fur trader for 5,000 deer skins. The stream beds of the Edwards Plateau also provided limitless flint. One of the oldest flint mining sites in North America is the Gault Site near Florence, Texas, right in the center of the Land of Good Water. Archaeological evidence shows flint mining there for at least 13,000 years."

Friends of Stephen F. Austin and Sam Houston

Tonkawa Chief Carita and Stephen F. Austin, leader of the American colonists in Texas during the 1820s and 1830s, collaborated to ward off the Comanche to the west and the Wichita to the north. "When Carita died in 1826, Tonkawa Chiefs Placido and Campo took over the primary leadership of the tribe and continued to work cooperatively with the settlers," writes O'Dell. "In 1838, Placido and Campo signed a treaty with then-President Sam Houston in the city of Houston."

'Shaking It Up': View Texas icon Liz Carpenter up close and personal in new documentary

Nurturing Austin in its infancy

Even before the Archives War, the city of Austin could have been strangled in its cradle if not for the Tonkawa allies. When President Mirabeau B. Lamar, usually no friend to Native Americans, arrived in 1839 to preside alongside the Texas Congress, he paid attention. "While Lamar had previously vowed the removal of all Texas Indians, he was advised and eventually consented to the Tonkawa Tribe to remain in the Austin area, because of their ability and willingness to fight against the often-deadly depredations of Comanche raiding parties on local settlers," O'Dell writes. "In August 1940, Lamar's decision not to expel the Tonkawa paid off. They were summoned and quickly joined Texian volunteers under Edward Burleson, Rangers and other militia to defeat the Comanche at the Battle of Plum Creek near Lockhart."

Life alongside the Tonkawa

Several eyewitness accounts of early Austin relate the easy familiarity between the Tonkawa, who in 1842 more than doubled the city's population from 200 to 450, and the Texians. For instance, William C. Walsh, who moved to Austin as a boy with his parents in 1840, published 14 of his memories under the title "Austin in the Making" in the American-Statesman in 1924, when he was the city's oldest resident. He recalled playing with Tonkawa boys, who helpfully painted him from "hair to toes, a brilliant red" so that he could become a war chief against the "hated Comanches." Cross-referencing this and other recorded incidents, O'Dell "unquestionably places the Tonkawa in Austin no later than August 1842."

Sounding the alarm

The presence of the Tonkawa off West Fourth Street not far upstream from the Colorado River ford at the mouth of Shoal Creek served as a tripwire for the possible presence of Comanche, who would race down the Shoal Creek Canyon on their raids. "When the Tonkawa or others sounded an alarm about encroaching Comanche, the settler and Tonkawa boys were so close to home that they could easily scatter to the protection of their respective mothers," O'Dell writes. Later reports confirm that the Tonkawa joined any posse to chase down raiders. "When they caught up with them, they would fight as long and hard as the whites," reported the Statesman in 1936.

'Steady. Courage.' Netflix's 'Rather' tells the story of one of America's top journalists

The possible triggering event

Normally, Texians would not allow Native Americans to live in their cities, nor did white leaders encourage trade with them. O'Dell thinks that the Tonkawa were invited to live in Austin by an oral agreement, and that the triggering event, a famously vicious raid in the summer of 1842, fits into the historical timeline. As described later in the century by J.W. Wilbarger, the attack against the Simpson family included the kidnapping of a widow's children by Comanche on West Sixth Street three blocks west of Congress Avenue. Her daughter was brutally murdered at Spicewood Springs, and her son was held captive for 18 months before being traded to another tribe. Historian Jeff Kerr called this "an attack that struck terror into even the stoutest hearts among Austin's citizenry." O'Dell concludes that had the Tonkawa, excellent trackers, been camped nearby when this happened, they might have saved the girl.

Why and when did the Tonkawa leave?

O'Dell could not find a definitive date or reason for the departure of the Tonkawa, but records suggest that they left the city during the fall of 1843, and were definitely gone by February 1844. Their withdrawal coincided with the reinstatement of Austin as the seat of government after several attempts by Houston to persuade legislators to stay away. Afterward, Houston directed that the Tonkawa stay out of settlements, "despite all the evidence that they had a very good record of coexistence and collaboration," writes O'Dell. The main body of Tonkawa drifted toward Bastrop and then were encountered at campsites near Gonzales, La Grange, San Marcos, San Antonio, Georgetown and elsewhere. Eventually, they endured three "trails of tears" of forced relocation before ending up in northern Oklahoma.

More: New book tells mind-bending history of Willie Nelson's Fourth of July Picnics

A state's chance for redemption

The Tonkawa never forgot Austin or Texas. Beginning in 1863, tribal members under Chief Castile trickled into Austin to ask for aid, employment as scouts and a permanent homeland in Texas. "When the Tonkawa made peaceful visits to the city in August 1865, townspeople remarked about the boldness with which the tribe interacted with the citizens," O'Dell writes. "It makes sense that the Tonkawa would roam with an easy demeanor the streets already so familiar to them." The legislature authorized some financial support and required the state to provide about 4,000 acres of public land to the tribe, but the promises were never kept.

A city's chance to honor the tribe

During the 20th century, Austinites gradually acknowledged their connections with the Tonkawa. In 1962, a study committee proposed naming the new lake, informally called "Town Lake," "Lake Tonkawa." But citizens protested. Even famed folklorist J. Frank Dobie, whose views by this time had become more progressive than previously, shrugged off the need for a name change. Many of the protests mentioned the red-herring charge of "cannibalism," referring to a wartime ritual long since abandoned by Texas tribes. It was not Austin's best day.

How to thank the Tonkawa

The Tonkawa, which at one point during the 20th century were rumored to have disappeared, have turned a corner as a group since the 1960s. They enjoy relative prosperity and population growth in the town of Tonkawa. Yet that is no reason to ignore the memory of the 1840s, when three-fourths of Austin's population abandoned the city, which was saved by the tribe. "The Tonkawa Tribe helped Austin in its time of greatest need, and this tribe has never even been thanked," O'Dell writes. "When we no longer needed their help, our city forcibly removed them. And in 1962, we quickly discarded a proposal to appropriately honor their memory. Towns surrounding Austin, for whom the Tonkawa did much less, have honored the tribe much more.

"Austin has done almost nothing."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today Network paper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: The Tonkawa tribe saved Austin. The city should honor with a monument