Atlanta queer-friendly Black church is source of solace for LGBTQ youth: 'I look over and see my people'

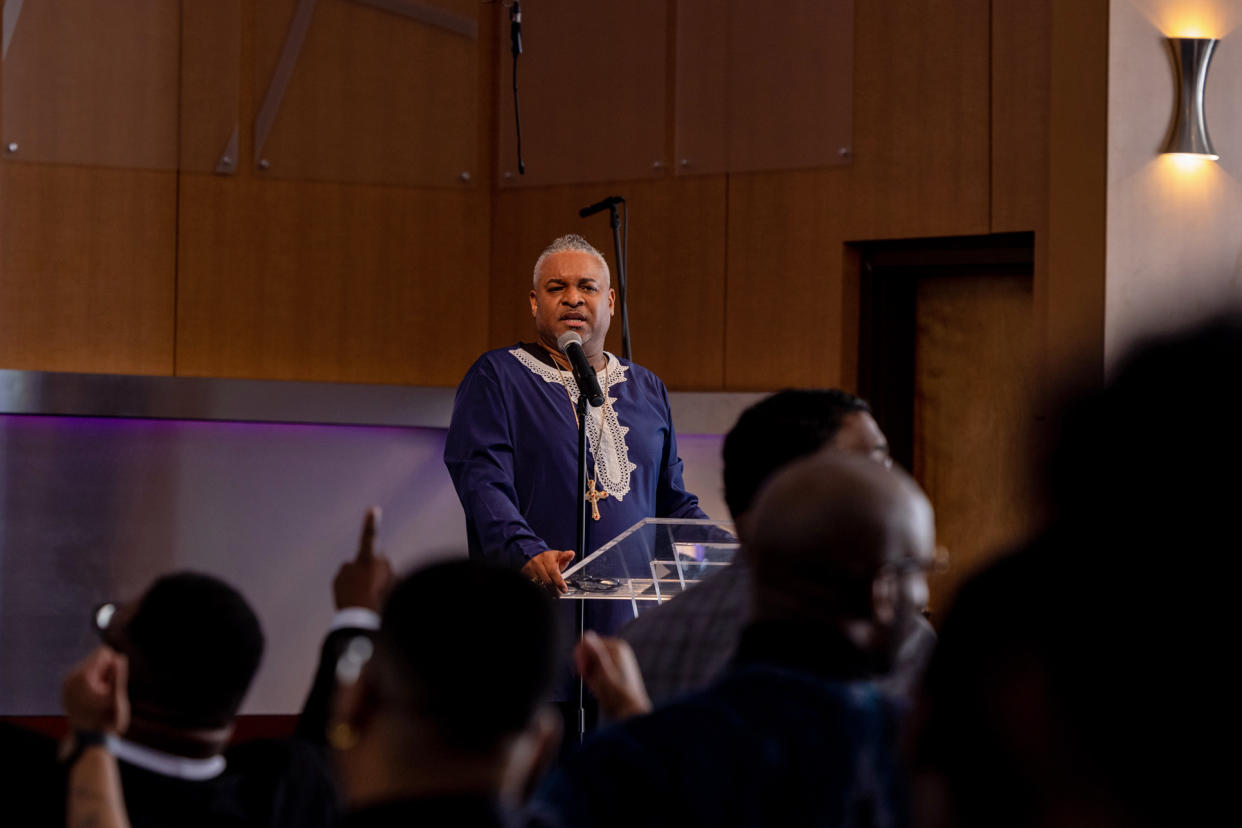

Bishop Oliver Clyde Allen III has a theory: Churches that oppress LGBTQI+ people are not churches.

Allen is the senior pastor and founder of The Vision Cathedral of Atlanta, which he began with his husband in 2005.

Today, the predominantly Black Pentecostal church has some 3,000 fellowshipped members, most of whom are LGBTQI+. And, like many organizations that serve marginalized groups, it rests on a historical foundation that the church fought to mold so that its members would be accepted.

“When people of color, Black people couldn’t find solace in white LGBTQ spaces, we created our own,” Allen tells Today.com about the church’s mission. “We created our own of everything, whether it was our own fraternities and sororities, our own institutions, our own churches.”

When Vision first purchased its cathedral in 2010 — it was previously Confederate Baptist Church — it sat at the intersection of Ormewood and Confederate Avenues. After much effort, Allen and his parishioners were able to have the latter street name changed to United Avenue in 2018.

The street name change wasn’t immediately welcomed by the surrounding community, Allen said. But the move advanced the church’s aim to encourage members to hold space for themselves in the face of efforts to hamper their identities.

“There was tension, and the neighborhood was having to adjust from a dwindling Confederate Baptist Church congregation to now this huge, Black LGBT majority congregation,” Allen said. “You can imagine the neighborhood was like, ‘What in the world.’”

Allen, 50, was born and raised in Los Angeles and calls his upbringing “religiously diverse.” Throughout his childhood and teen years, his family members attended Baptist, Pentecostal and Seventh-Day Adventists churches.

Like many of his church’s congregants, he often stood in pews while listening to the words of pastors who condemned people like him. But these leaders, he points out, were often surrounded by LGBTQI+ members who made the church’s choirs more lively, helped with collections and filled the seats.

These dynamics, combined with sermons that decried non-heterosexualities as abominations, are part of the reason why Allen sees himself as more than a leader of a Black or gay church.

More than a preacher, Allen describes himself as an abolitionist, someone whose job is to spread a message of freedom and acceptance, two elements that he argues are the fundamentals of Christian belief.

“I grew up in something that called itself a church. [It] couldn’t have been a church,” he asserts. “Jesus Christ didn’t say anything about gay people and said everything about liberating people. From all types of oppression, [including] sin.”

At Vision, churchgoers are encouraged to embrace their faith through education, community support and the encouragement of political activism.

Its ministries focus on providing food and clothing collections for the homeless, HIV and AIDS testing and support, and addressing health and wellness, particularly for Black LGBTQI+ members.

The church also works to develop spaces that nurture those who have been turned away by their families, a common problem facing its transgender members.

Tonyka McKinney, 38, has been a member of Vision church since 2009. She said that the year before she joined, her entire family cast her off after she came out to them as a lesbian.

“I was at my lowest point, like, I was absolutely suicidal when I walked into (Vision),” she said. “The internalized negativity had just taken over. I didn’t want to be alive anymore. I didn’t know a way out because I hated myself, because that’s what I was taught, to hate a person who was gay.”

The south Georgia native described her upbringing in a “very Christian” Black evangelical home, where family members like her mother, her uncle and grandfather often stepped up to the pulpit as pastors.

“My mother was in labor with me on a pew at church. She had to leave church to go have me,” she explains, adding that between the ages of 18 and 24, she ventured outside of her family’s church to attend six to eight other churches.

At each church, McKinney became skilled at code-switching. She swapped her slacks for skirts and left no questions open when it came to her sexuality. But at Vision, McKinney said she no longer feels compelled to pretzel herself into a category to gain favor.

“I can actually be myself,” she said. “I can go to church and sit next to my wife, and no one’s going to be like, ‘What is this?’”

Four years ago, Hakim Asadi, 33, joined Vision after deciding to walk away from churches altogether in 2015.

Like McKinney, Asadi also grew up in a religious household where much of his community and daily activities centered around church life. The counselor and social worker grew up in a religious family in upstate New York, where his grandmother oversaw a church that she had founded in 1955.

Asadi said his family ties to the church did not shelter him from stigmas as people began to realize he was gay. He recalls hearing murmurs about him running through the pews during services.

“The first (feeling) that comes to my mind is shame,” he said. “There are parts of me that I wasn’t able to explore freely and openly and safely because it wasn’t talked about, it wasn’t accepted. It was frowned upon.”

Just by being himself, “I was ‘dying and going to hell,’” he recalled thinking.

Today, he is a minister in training at Vision and works for the office of the bishop. Being able to attend services with a previous romantic partner without getting judgmental looks affords Asadi mindfulness in church.

“There’s an essence of freedom here and shared freedom because church is about community,” he said. “I can look over and see my people.”

According to McKinney, although the majority of church members are LGBTQI+, Bishop Allen’s sermons have “nothing to do with whether or not you’re gay or straight.”

“I’ve never had to hear from his pulpit that something was wrong with me,” she said. “I hear the complete opposite: that God loves me. And God loves everyone.”

These days, the church’s missions are ever-expanding, with members like Asadi and McKinney providing education outreach to young people who are at risk.

The Trevor Project’s 2020 national survey on LGBTQ youth found that 44% of Black LGBTQI+ youth seriously considered suicide in the 12 months it conducted its study.

To save lives, Vision works with people in homeless communities and on university campuses. Just eight miles away from Vision is Morehouse College, Allen’s alma mater, where many of the church’s members are enrolled.

These students and members, even outside of Vision, are invited to take part in the church’s social events, such as picnics and fish fries, which have long served as the foundation of Black families and communities in the South. There are also Bible study events throughout the week.

“People can get the love and care that they would normally get from their grandmother or their auntie,” Allen said.

As Allen puts it, Vision models a family dynamic in the same way that underground ballroom communities, gay dive bars and gay villages became surrogate spaces for those who were shunned for coming out in decades past.

“When I do the benediction, my husband stands next to me, and our children stand in front of us,” he said. “I don’t have to say anything like we’re a normal family. People see themselves in us.”