As more states reopen, Georgia defies predictions of coronavirus resurgence. What's the lesson for the rest of the country?

On April 24, as more than 25,000 Americans continued to test positive for COVID-19 each day, Georgia became the first U.S. state to initiate the fraught process known as “reopening.”

First it allowed hair salons, gyms, barber shops, tattoo parlors and bowling alleys to resume operations. Dine-in restaurants and movie theaters followed a few days later.

Today much of the state is open for business, under guidelines including a 6-foot social distancing rule.

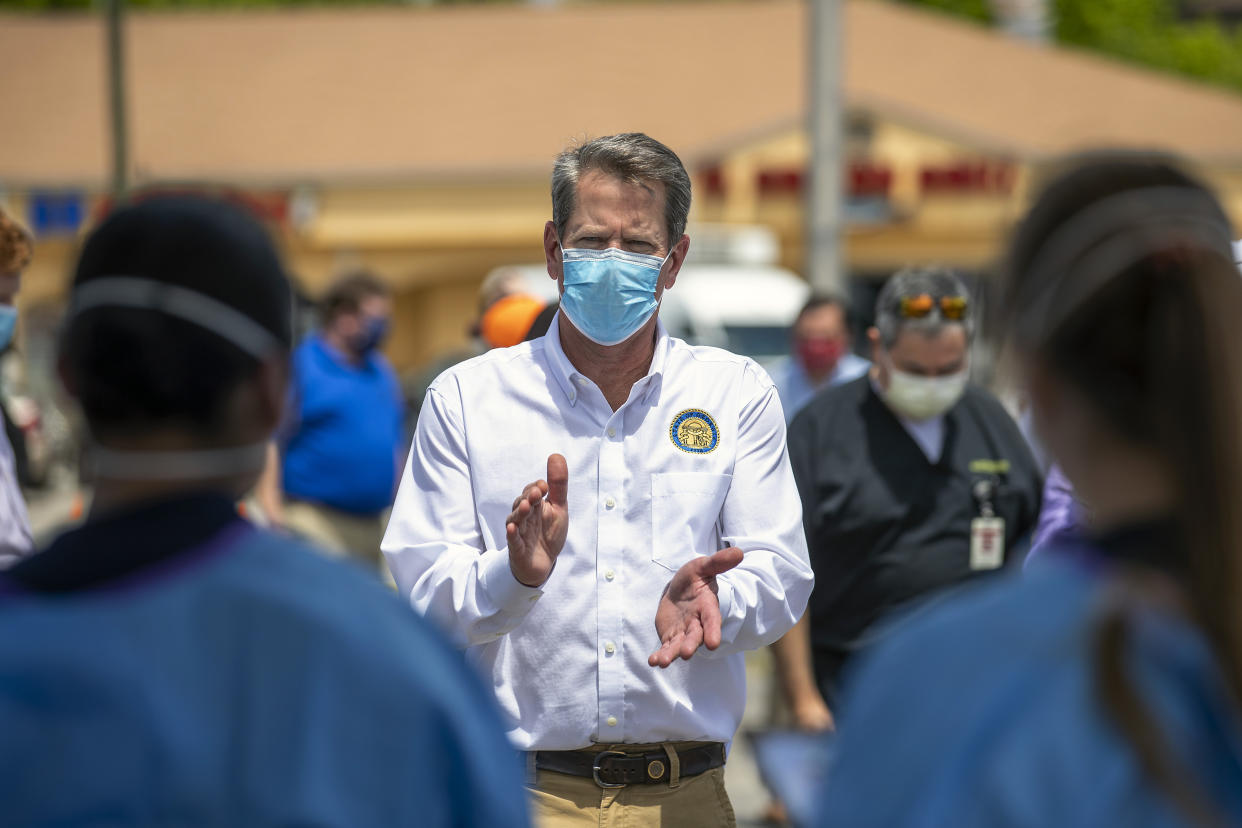

The move was controversial, to say the least. In the New York Times, Keren Landman, an Atlanta-based physician, epidemiologist and journalist, accused Republican Gov. Brian Kemp of potentially “setting us up for a punishing new wave of infections” by volunteering Georgia as “the nation’s canary in this particularly terrifying coal mine.”

Even President Trump said he “disagree[d] strongly with [Kemp’s] decision.”

But now 26 days have passed since the state started to reopen — and that punishing new wave of infections has not materialized. In fact, according to a database maintained by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Georgia’s rolling seven-day average of new daily cases — an important metric that helps to balance out daily fluctuations in reporting — has fallen for three weeks in a row.

Those figures are undisputed — despite a clumsy effort by state officials to present the data in a way that made them look even better. And they are a lot better than the experience in two other states that are moving to end lockdowns, Florida and Texas.

For the seven-day period ending on May 4, Georgia’s daily average stood at 746 cases.

By May 11, the average had fallen 12.6 percent to 652 daily cases.

By May 18, it had dropped to 612 cases, a further decline of 6.1 percent.

At the same time, Georgia’s seven-day average of COVID-19 hospitalizations fell from 1,432 on May 4, to 1,239 on May 11, to 1,049 on May 18 — a three-week decline of 26.7 percent.

The numbers reflect a slowing in transmission. According to the AJC database, Rt — an epidemiological statistic that represents transmissibility, or the number of people a sick person infects at a particular point in an epidemic — fell from 1.0 on May 4, to 0.94 on May 11, to 0.88 on May 16. An Rt below 1 indicates that each person infects, on average, less than one other person.

So does Georgia’s experience mean the canary has survived the coal mine? And if so, what would the state’s survival mean for the rest of America?

To one degree or another, all 50 states have now started to reopen. But the process has advanced slowly, in fits and starts — especially in the Northeast and on the West Coast, where Democratic governors have tended to be more cautious than their Republican counterparts in the South, the Midwest and the Mountain West.

Ultimately, the answer to whether other states should follow Georgia’s lead and reopen more fully is that it depends.

According to the latest data, it’s true that Georgia’s seemingly premature reopening hasn’t produced a surge of new cases … yet.

That yet is important. The coronavirus doesn’t just disappear on its own. Wherever and whenever people interact — especially indoors, for an extended period of time, at a distance of less than 6 feet, without wearing a mask — it will have an opportunity to spread. Georgia is not some magical exception. It is entirely possible that the curve there will start bending upward instead of downward in the coming weeks, especially if residents get a false sense of security and really let down their guard.

But 26 days is enough time to draw some tentative conclusions. When positive-looking data started to emerge from Georgia shortly after reopening, experts were quick to note that its declining daily case counts were actually a window into the past. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the virus can incubate for up to 14 days before symptoms begin (though research shows the vast majority develop symptoms in less than 11.5 days). Then a patient has to get tested. Then a lab has to process that test. Then that lab has to send back a positive result. Then that result has to be reported to public health authorities. The upshot is that the first two weeks of post-reopening numbers still reflect the state of the epidemic before reopening. It’s only in week three or so — i.e., now — that they even start to reveal anything about the impact of lifting lockdown.

That’s why Georgia’s latest seven-day average of new daily infections — down by 6.1 percent from the previous week — is so encouraging. Where they go from here is unpredictable. Infections could continue to decline. The rate of decline could slow down; in fact, it may be slowing already, given that the previous seven-day average represented a 12 percent drop from the week before. It could plateau. There could be fewer cases than before — but not as few as there would have been in lockdown. That’s only logical.

But unless infections start to climb — unless the transmission rate crosses that 1.0 barrier and the epidemic starts to grow exponentially again — reopening could be declared a relative success.

If that happens — and again, that’s a big if — it would tentatively answer the key question in the debate over reopening: As government restrictions are relaxed, can we trust individuals, businesses, organizations and communities to practice and enforce enough social distancing to help keep the epidemic under control?

The truth is, reopening isn’t a return to normal, and most Georgia residents aren’t behaving — yet — like it is. Businesses have to keep people 6 feet apart. Masks are recommended (although not required) in public places. The latest Yahoo News/YouGov poll found that three-quarters of Americans now say they will “voluntarily continue to practice social distancing even after official restrictions are lifted” and “stay 6 feet away from others whenever possible”; the share who say they will wear cloth masks in public has climbed 11 points (to 61 percent) since late April.

Meanwhile, the most recent Google mobility data shows that Georgians are getting around more after reopening — but still not as much as they were before the pandemic. Visits to retail and recreation establishments are 16 percent lower than the pre-coronavirus baseline. Trips to grocery stores and pharmacies are 2 percent lower. Transit stations are 39 percent lower. Workplaces are 40 percent lower. Only relatively safe outdoor spaces like parks and beaches have seen an increase in activity, presumably reflecting the change of season as well as the end of stay-at-home orders.

That’s the balance reopening needs to strike if it’s going to work: fewer official restrictions in exchange for more individual and community responsibility.

That said, individuals can control only so much during a global pandemic. Government has a responsibility as well. And this is where Georgia’s tentative progress could take a turn for the worse.

As Gov. Kemp has pushed to reopen, his administration has consistently and repeatedly failed to relay accurate data about the state’s coronavirus epidemic. As the AJC has reported, Kemp’s team has deleted a daily count of completed tests, making it difficult for the public to determine if Georgia is meeting a key White House criterion for reopening. It has constantly changed the metrics it publishes while shifting its method of counting cases, confusing ordinary Georgians. Here’s how the paper described one late April revision:

Gone is a county-by-county list of reported deaths by gender and age, which locals were using to verify their own counts. Some figures are written in such small type that they are no longer legible. Others are 10 times as large as they once were. Much of it is now published in a format that makes it difficult for researchers to use.

Last week, Kemp and his team made national headlines when they published a graph that was arranged out of chronological order in order to make cases look like they were declining more quickly than they actually were; after intense online mockery and criticism, the state was forced to fix its chart. Then on Monday, the Georgia Department of Public Health admitted another error, tweeting that it had accidentally included the results of serological antibody testing — which detects evidence of a previous infection — along with the number of those who actively have the virus.

Similar issues are clouding the data in other quick-to-reopen states, such as Texas and Florida. The problem here, at least when it comes to Georgia, isn’t that you can’t find the real data if you want (the AJC dashboard is exceptional) or even that the real data isn’t encouraging (it is). The problem is that all the meddling and mistakes call into question whether leaders in Georgia (and Texas and Florida) will follow that data wherever it leads — even if it’s not telling them what they want to hear.

That shift can happen quickly. The numbers out of Texas and Florida, for instance, are not nearly as heartening as Georgia’s. Florida saw a 14 percent decline in its seven-day average case count (from 680 to 584) between May 4 and May 11 — but by May 18 that average had shot back up to 780. Meanwhile, Texas’s seven-day average has continued to climb, from 1,066 on May 4, to 1,110 on May 11, to 1,257 on May 18.

In a sign, perhaps, of things to come, churches in both Texas and Georgia that briefly reopened for in-person worship services have had to close again as the virus spread in their pews. Holy Ghost Catholic Church in Houston closed after five leaders tested positive last weekend, following the death of one priest who had been diagnosed with pneumonia. In Ringgold, Ga., Catoosa Baptist Tabernacle started in-person services again in late April but stopped on May 11 after learning that members of several families had contracted the virus. And on Tuesday the CDC released a report about an outbreak in March at a rural Arkansas church: Of the 92 people who attended the church between March 6 and March 11, 35 tested positive and three died, the report said. Investigators found that 26 other contacts of these churchgoers later tested positive and one died.

In the absence of stay-at-home orders, these are exactly the sort of super-spreader events that can trigger a larger outbreak. To protect their residents, authorities in Georgia and elsewhere need to immediately recognize what’s happening — and the only way they can do that is by respecting the data.

They also have to be ready to respond. And that could be another problem going forward. As reopening proceeds, the U.S. should be doing more than 900,000 diagnostic tests per day in order to safely phase out restrictions, according to a new report by Harvard’s Global Health Institute — a big jump from its earlier projection of between 500,000 and 600,000 daily tests and more than twice as many as the country’s highest daily number so far.

Because the pandemic has affected each state differently — Georgia’s outbreak was relatively mild — the Harvard institute also simulated how many tests each state needed to conduct daily by May 15, at a minimum. Georgia’s target number was 25,979.

The actual number of tests it conducted that day, however, was about a third of that goal: 9,507.

Since then, Georgia has shown it has the capacity to hit Harvard’s mark; on Sunday the state reported 30,106 new tests. But the numbers so far this week are much lower: just 13,114 on Monday and 13,867 on Tuesday, or roughly half the required amount.

Reopening in Georgia may be going fine — for now. But without reliable data and widespread testing, things won’t be fine if and when that changes. The rest of the country should take note and proceed accordingly.

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more: