Five questions about the Democratic race Super Tuesday could answer

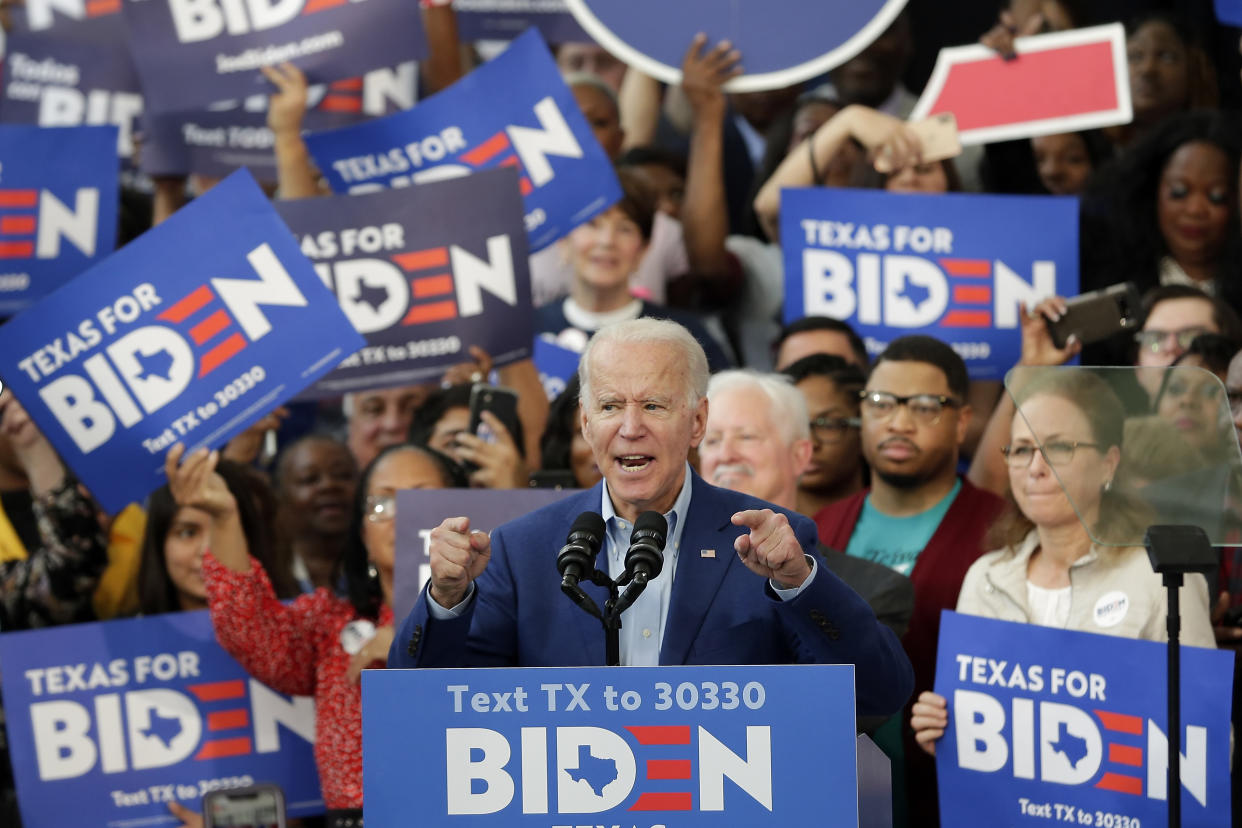

Buckle up. After Saturday, the 2020 Democratic primary shifted into overdrive; things are moving so fast now, it’s all becoming a blur. Joe Biden clobbered the competition in South Carolina. Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar dropped out and endorsed Biden; Beto O’Rourke endorsed Biden, too. Bernie Sanders announced a record-setting one-month fundraising haul of $46.5 million. Elizabeth Warren’s campaign revealed that her plan is to win the nomination at a contested convention in July, even if she doesn’t win any primaries before then. And those still running — Biden, Warren, Sanders, Michael Bloomberg and Tulsi Gabbard — fanned out across several of the 14 states (California, Texas, Virginia, Minnesota and others) that will award a full third of the Democratic Party’s 3,979 delegates on Super Tuesday.

The good news is that Tuesday’s voting, which also takes place in American Samoa and among citizens abroad, will do more to clarify the contest than anything else that’s happened so far. Here are five pressing questions that Super Tuesday should answer.

How big is Bernie’s ‘movement’?

Every time he speaks, the Vermont senator and self-described democratic socialist says his campaign is a “grassroots movement” that will defeat President Trump by inspiring “the largest voter turnout in history,” particularly among young voters, new voters and voters of color.

But after four early state contests there’s little evidence to support Sanders’s claims. Overall turnout in the caucus states where Sanders won the most votes (Iowa and Nevada) was below the high-water mark of 2008 and only modestly higher than in 2016. In the one primary state Sanders won (New Hampshire), turnout was “on par” with “the past two cycles in which only one party had a competitive primary,” according to the New York Times. The only state where turnout really beat expectations was the state Sanders lost by nearly 30 percentage points: South Carolina.

More worryingly for Sanders, a New York Times analysis found that the demographic groups Sanders is counting on haven’t been turning out in “historic” numbers. The Times reported that in the Iowa precincts where Sanders won, turnout increased by only 1 percent from 2016; that turnout increased far more in the New Hampshire townships where Buttigieg and Klobuchar won than where Sanders won; that the share of young voters remained essentially unchanged everywhere; and that the share of first-time voters actually decreased.

Sanders is still running a very strong campaign; his Latino outreach in particular has been impressive, and it should boost him Tuesday in California and Texas, where most of the day’s delegates are concentrated. He is doing well among younger black voters and working-class white voters of all ages. He is likely to lead the delegate count after Super Tuesday by anywhere from 60 delegates to as many as 400, depending in large part on how dominant he is in California, where he banked a lot of early votes in the days before Biden upended the race with his strong showing in South Carolina.

But in a party whose main priority is beating Trump, Sanders has to prove he’s the one who can do it. Heavy youth voter and new voter turnout in swing states including Virginia, Colorado, Minnesota and North Carolina, and swing districts in California and Texas, would be a good start. If Sanders doesn’t get that, worries about his electability will continue to grow.

Can Biden catch up?

South Carolina showed just how dominant Biden is among black voters, and there will be plenty more casting ballots on Super Tuesday, especially in the South. The primary electorate in Texas is 19 percent black; Virginia, 26 percent black; North Carolina, 32 percent black; Tennessee, 32 percent black; Alabama, 54 percent black; Oklahoma, 14 percent black; and Arkansas, 27 percent black.

But the real question for Biden — the one that will determine whether his post-Palmetto State bounce is big enough to keep Bernie from building an insurmountable delegate lead — is how much and how fast he can expand his base beyond black voters to include the majority of Democratic primary voters who have so far sided with candidates other than Sanders.

In that quest, the suburbs will be key, and there are a lot of big, important suburbs set to vote on Super Tuesday: Northern Virginia; Raleigh, N.C.; Charlotte, N.C.; Dallas; Houston; Orange County, Calif. These are the moderate, affluent, well-educated, news-attuned places that in 2018 powered Democrats to their biggest House victory since Watergate. They’re also the kind of places where Buttigieg and Klobuchar were running the strongest before they dropped out.

Do wavering voters there and elsewhere coalesce around Biden as the sole “Stop Sanders” candidate now that the rest of the field has narrowed and neither of the remaining alternatives (Bloomberg and Warren) seems to have much of a path to the nomination? The South Carolina results suggested they might. There, Biden didn’t just win black areas; he also “won areas dominated by groups he has struggled to connect with, notably white and higher income voters,” according to a Washington Post analysis. “These areas also showed some of the largest turnout increases in the state.”

Before South Carolina, Biden was lagging behind Sanders (and in some cases, Bloomberg) in the Super Tuesday polling. Yet the first national poll out after S.C. showed Biden gaining 7 points overnight, putting him in a near tie with Sanders. There isn’t enough time left for pollsters to measure similar movement in individual Super Tuesday states. But if that momentum holds and is reflected in Tuesday’s results, it could give Biden the springboard he needs to challenge Sanders for the nomination.

Where do Buttigieg and Klobuchar voters turn?

The conventional wisdom says they will turn to Biden; both dropouts endorsed him and overlapped with him in tone and ideology.

But second-choice math isn’t always so simple. The most recent Quinnipiac poll showed Klobuchar and Warren as the top second choices for Buttigieg supporters at 26 percent, followed by Biden at 19 percent. A new Morning Consult poll projected that Buttigieg’s voters would divide roughly evenly among Sanders, Biden, Warren and Bloomberg. As for Klobuchar, 21 percent of her supporters named Buttigieg as their second choice — which just adds to the confusion — followed by Warren and Biden at 17 percent.

It’s unclear, then, where the orphaned supporters of Buttigieg and Klobuchar will end up. But party rules suggest that Biden and perhaps even Warren are likely to benefit more than Sanders. To win delegates, candidates need to clear 15 percent statewide and across individual congressional districts. The pre-South Carolina polling suggested that Biden and Warren could miss that cutoff in some places; Sanders, in contrast, was generally polling above 15 percent everywhere. That means each extra vote Biden or Warren gets from a former Buttigieg or Klobuchar backer could help make the difference between some delegates and no delegates. But Sanders stands only to pad his margins.

WTF is Warren up to?

The Massachusetts senator is a bit of a mystery at this point. She hasn’t won any delegates since Iowa, and she actually finished behind Buttigieg in South Carolina. On the stump Saturday in Houston, Warren admitted that she would be “the first to say the first four states have not gone exactly as I hoped,” and her campaign manager Roger Lau is openly predicting that “no candidate will likely have a path to the majority of delegates needed to win an outright claim to the Democratic nomination.”

“Milwaukee is the final play,” he wrote Sunday on Medium, referring to the site of July’s Democratic National Convention. It is there, Lau added, that Warren will “ultimately prevail.”

It is true, as the Warren campaign likes to point out, that she got a big fundraising bump after two standout debate performances in late February. It’s true that she has 1,000 staffers across 31 states. It’s true that unlike Klobuchar and Buttigieg, she has been polling above the 15 percent delegate threshold in states such as California, Massachusetts, Colorado and Maine. She will likely win some delegates Tuesday.

“[Warren] enters Super Tuesday with lots of groundwork laid, two fantastic debate performances during early voting in upcoming states and an overall position of strength,” Maria Langholz, press secretary for the Warren-aligned Progressive Campaign Change Committee, told Politico.

But then what? Does Warren really plan to continue campaigning in primaries and caucuses for another three months while waiting for either Sanders or Biden to implode and for the Democratic Party to respond by awarding her the nomination in Milwaukee, even though she will likely have fewer votes and delegates than either of them?

Or is she competing for something else: influence, the vice presidency, the chance to play kingmaker at a contested convention by sending her delegates one way or the other?

“A convention working its will means that people have the delegates that are pledged to them and they keep those delegates until you come to the convention,” Warren said at the Nevada debate.

“Pledged” delegates are expected — although not legally required — to support their candidate on the first ballot, and if the convention goes to a second vote they are free to follow their consciences. Still, Warren might well come to Milwaukee with a contingent of loyalists who will follow her lead.

If that’s her plan, Super Tuesday will largely determine how many delegates Warren has — and whether she can continue doing whatever it is she’s doing.

When will Bloomberg drop out?

Buttigieg is out. Klobuchar is out. That makes the former New York City mayor the last moderate standing who isn’t Joe Biden. With an enormous fortune at his disposal, Bloomberg spent more than $500 million on ads — plus additional untold sums on staff and organization — to lift his poll numbers into the double digits nationally and across the Super Tuesday states, while his rivals were quaintly campaigning in Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina, where Bloomberg did not compete.

All reports suggest that Bloomberg plans to stay in through Tuesday and see what kind of return he gets on that massive investment. (“I’m in it to win it,” he said Monday in Virginia.) But Bloomberg’s candidacy was always premised on a Biden collapse, and now that Biden is making a comeback, there will be significant pressure on him to step aside if the former VP outperforms him on Tuesday. It remains to be seen whether Bloomberg will succumb to such pressure; he certainly has the resources to resist it and continue siphoning moderate votes from Biden.

But if he does give in and drop out, expect Biden HQ to rejoice. Bloomberg entered the race in part to stop Sanders, and he has committed to spending whatever it takes to defeat Trump and support Democratic candidates. In a protracted battle with Sanders, Biden could benefit from Bloomberg’s largesse.

Read more from Yahoo News: