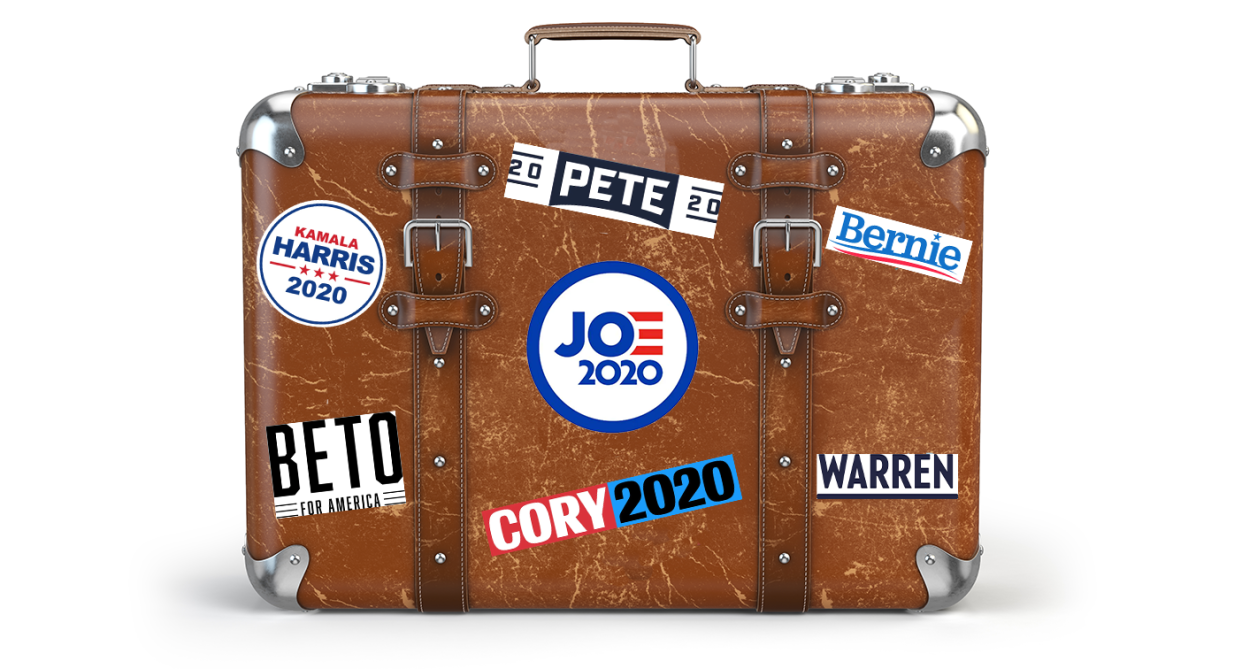

The biggest baggage weighing down the top 7 presidential hopefuls in the Democratic field

Just as in past cycles, each of the presidential hopefuls in the 2020 Democratic field enters the race with political baggage in tow. How a given candidate deals with it will help determine the party’s eventual nominee as well as whether he or she will prevail in the general election.

During the 2008 campaign, for instance, Democratic Sen. Barack Obama successfully spun his relative inexperience and relationship with controversial pastor Jeremiah Wright to his advantage. Eight years later, however, former Florida Republican Gov. Jeb Bush couldn’t convince Republicans that his family ties were a positive attribute in his own quest to become president.

This year’s crop of candidates has its own list of potential vulnerabilities, and the eventual nominee will face an incumbent president who has proven himself adept at exploiting weaknesses. Here’s a look at the liabilities hiding in plain sight for the seven highest-polling contenders for the Democratic nomination. The order of the list was determined using RealClearPolitics’s average of recent polls.

The former vice president has been in politics long enough that his past votes and statements on issues such as busing and sexual harassment have opened him up to criticism from more liberal opponents in the 2020 field. Perhaps no single issue has come back to haunt him as much as his support of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 — a bill that provided funds for 100,000 police officers and $9.7 billion toward prisons.

While the legislation led to a decrease in overall crime, advocates of criminal justice reform have criticized provisions of the law that contributed to a drastic increase in the U.S. prison population. In a 2007 presidential debate, then-candidate Biden bragged about his involvement in the bill’s passage, calling it the “Biden crime bill.”

Critics of the legislation have also pointed to provisions that incentivized states to pass tougher sentencing requirements in exchange for federal dollars. Few states, however, actually took advantage of those incentives.

Biden has steadfastly rejected the view that the law led to mass incarceration. He has also defended the legislation by pointing to the Violence Against Women Act and assault weapons ban, two provisions popular with liberals that were included in the bill.

In a speech this year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, however, Biden apologized for some tough-on-crime policies from the 1980s and ’90s. “I haven’t always been right,” he said, without naming specific legislation. “I know we haven’t always gotten things right, but I’ve always tried.”

Warren has claimed Native American ancestry since at least 1986, when she wrote “American Indian” on an application for entry to the State Bar of Texas. While an investigation by the Boston Globe concluded that her purported ethnicity did not aid her legal career, critics have alleged that she sought to use a claim of Native American blood for just that reason. President Trump often derides Warren for her claims to Cherokee ancestry, calling her “Pocahontas.”

By the way, @realDonaldTrump: Remember saying on 7/5 that you’d give $1M to a charity of my choice if my DNA showed Native American ancestry? I remember – and here's the verdict. Please send the check to the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center: https://t.co/I6YQ9hf7Tv pic.twitter.com/J4gBamaeeo

— Elizabeth Warren (@ewarren) October 15, 2018

In October 2018, as Warren was mulling a presidential run, the Massachusetts senator released the results of a DNA test to the Globe in an attempt to silence Trump and other Republicans. As a public relations move, taking the test backfired, provoking ire from Native Americans. Chuck Hoskin Jr., secretary of state of the Cherokee Nation, said at the time that Warren dishonored “legitimate tribal governments and their citizens.”

Since then, Warren has apologized to the Cherokee Nation, noting that she grew up believing that she was descended from Native Americans.

“I grew up believing with my brothers, this is our family’s story. And it’s all consistent from that point in time,” Warren told reporters in February. “But as I said, it’s important to note I’m not a tribal citizen, and I should have been more mindful.”

Warren was raised in Oklahoma, where the Cherokee Nation is based, and her family has long claimed roots in the Delaware and Cherokee tribes. While Warren has run a strong campaign in the months following the DNA test, the issue continues to linger as a possible liability. In a May interview on “The Breakfast Club” radio show, co-host Charlamagne Tha God caught Warren off-guard by comparing her to former NAACP chapter president Rachel Dolezal. “You’re kind of like the original Rachel Dolezal, a little bit. Rachel Dolezal was a white woman pretending to be black,” Charlamagne said.

Long before he rose to national prominence in the 2016 presidential election, the independent senator from Vermont had been outspoken about his support for socialist principles. While Sanders proudly describes himself as a democratic socialist, a 2019 Gallup poll found that 51 percent of Americans believe some form of socialism would be a bad thing for the country. Forty-three percent said it would be good.

Sanders’s past praise of socialist leaders gives opponents a wealth of material to use to criticize his judgment. When he was mayor of Burlington, Vt., in 1985, Sanders defended Cuban leader Fidel Castro in an interview with a local TV station, noting that while Castro wasn’t perfect, “he educated their kids, gave their kids health care, totally transformed the society."

Sanders also often praised Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista movement in Nicaragua. He traveled to the country in 1985 to meet Ortega at a time when the Reagan administration was covertly funding a guerrilla war against the Sandinistas.

Sanders has been criticized for choosing to visit the Soviet Union in 1988 for his 10-day honeymoon with wife Jane — a trip he cites as essential to helping form his ideas on foreign policy.

His critics maintain that his affinity with socialist leaders and policies puts him outside the American mainstream and makes him unelectable. During his State of the Union address in February, Trump said he would make socialism a key talking point regardless of which Democrat wins the party’s nomination for president.

“We are alarmed by the calls to adopt socialism in our country,” Trump said, adding, “Tonight we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.”

In a June speech at George Washington University, Sanders compared his focus on “economic freedom” with the New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and entitlement programs like Social Security that Americans have come to view positively. Sanders said the New Deal was socialist and that FDR faced intense criticism from conservatives over his expansion of government programs.

“We must recognize that in the 21st century, in the wealthiest country in the history of the world, economic rights are human rights. That is what I mean by democratic socialism,” he said.

Sanders rejects the idea that the government should own the means of production, which is a central tenet of socialism. Instead, he focuses his version of democratic socialism on issues like universal health care and income inequality.

From the start of her presidential campaign, the senator has been forced to respond to criticisms from the left wing of the Democratic Party that portray her as “a cop.” This attack, which posits that she was a less progressive prosecutor than she claims, stems from her record in two prominent law enforcement positions: San Francisco district attorney and California attorney general.

Harris’s detractors point to her support for a policy that allowed prosecutors to press charges against the parents of truant students. While district attorney, Harris herself did not send parents to jail, but some jurisdictions charged parents for truancy, as they enforced the policy after she went on to become attorney general. Harris has also been criticized for her initial reluctance to mandate a standard for police body-camera programs.

Knowing that her record could prove a liability in a primary for a party perceived to have moved to the left during Trump’s time in office, Harris crafted a campaign whose double-entendre attempts to unify her prosecutorial experience with populist politics: “Kamala Harris for the People.”

In a June 8 speech in South Carolina, a state important to the Democratic primary race because of its high proportion of black voters, Harris directly addressed those critical of her criminal justice record.

“There have been those who have questioned my motivations, my beliefs and what I have done,” Harris said at the state’s NAACP Freedom Fund dinner in Columbia. “But my mother used to say, you don’t let people tell you who you are. You tell them who you are.”

To that end, Harris has sought to reframe the years she spent as a prosecutor. As district attorney, for instance, she notes that she challenged California’s three-strikes law, which allowed up to a life sentence for a third felony conviction. In recent weeks she has doubled down on her strategy, portraying her background as having prepared her to take on Trump in the general election.

“I prosecuted the big banks when they preyed on homeowners. I prosecuted the pharmaceutical companies when they preyed on seniors,” Harris said while campaigning in Iowa on July 3. “I have prosecuted transnational criminal organizations when they preyed on women and children. I know predators, and we have a predator living in the White House.”

After a police officer in South Bend, Ind., shot and killed a black man in June, Buttigieg, the city’s mayor, was forced to leave the campaign trail to address rising tensions in the city. Some residents have accused the 37-year-old of not putting enough effort into reforming the city’s police department and diversifying its police force. In 2018, South Bend spent $1.5 million on police body cameras, but the officer involved in the shooting didn’t have his on.

Already facing dismal polling numbers with black voters before the shooting, Buttigieg was asked at the first Democratic primary debate in June about his failure to diversify the South Bend police force during his two terms as mayor. He had an honest response.

“I couldn’t get it done. My community is in anguish … and I’m not allowed to take sides until the investigation comes back. The officer didn’t have his body camera on. It’s a mess. We are hurting,” Buttigieg said.

The investigation into the officer-involved shooting is still ongoing. In response to the shooting, Buttigieg directed his police chief to mandate that all on-duty officers in the city turn on body cameras whenever interacting with civilians.

With the incident drawing attention to Buttigieg’s troubles attracting support from African-Americans, the presidential candidate has begun campaigning on a promise to address “systemic racism” in the country if elected.

Last week he released his “Douglass Plan,” an 18-page list of proposals to help black Americans. Named after abolitionist Frederick Douglass, some of the plan’s proposals focus on criminal justice reform — reducing incarceration rates by half — while others aim to create health equity programs and award a quarter of government contracts to minority business owners.

America rebuilt Europe after WWII with the Marshall Plan. Now we need that same level of investment right here at home with the Douglass Plan. If we do not tackle systemic racism and racial inequality, it will unravel the entire American project. pic.twitter.com/XViUw5YUnu

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) July 12, 2019

The former U.S. representative from Texas rose to star status among Democrats during his unsuccessful campaign to unseat Sen. Ted Cruz. He served three terms in the House, representing a district along the U.S.-Mexico border that includes El Paso, his hometown. During his time as a congressman, O’Rourke was the primary sponsor for only three bills that were enacted, according to GovTrack.

While he supports progressive proposals like the Green New Deal and Medicare expansion, O’Rourke hasn’t released many original policies of his own. His signature proposal so far has been a new voting rights act to make voting easier and reduce corporate influence in politics.

This has led many pundits, like the Washington Post’s Kathleen Parker, to conclude he is “not ready for prime time.” Even many of O’Rourke’s supporters in Texas wonder whether the White House is calling. A June Quinnipiac University poll of 400 Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters found that 60 percent would prefer he run in Texas against Sen. John Cornyn, the Republican incumbent.

“Well, I’m grateful that ultimately it’s up to voters and they’ll have a chance to meet with me, question me, listen to me. And I’ll have a chance to listen to them,” O’Rourke said in an interview with “CBS This Morning” back in March. Since then his polling numbers have gone nowhere fast.

O’Rourke did raise $6.1 million in the first 24 hours of his campaign — the highest amount ever taken in by a presidential candidate in a single day. He similarly broke fundraising records in his 2018 run against Cruz. O’Rourke hasn’t released his second-quarter fundraising numbers, which could be an indication of exactly how many voters are listening.

In early July, O’Rourke himself said he hadn’t seen the totals yet. “I’m going to find them soon,” he told reporters while campaigning in Iowa.

Booker, the junior senator from New Jersey, has focused his campaign on criminal justice reform, Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. He’s also pledged not to take money from political action committees or lobbyists, a common refrain among 2020 Democrats. But before he made that last promise, Booker had, during his tenure in the Senate, already received hundreds of thousands in donations from corporations.

In fact, Wall Street gave more money to Booker in 2014 — totaling $2,223,220 — than any other member of Congress. Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell came in second for Wall Street donations that year. In 2017, after progressives criticized him for opposing a bill sponsored by Sanders that would lower drug prices, Booker said he put “a pause” on donations from the pharmaceutical industry.

When he announced his presidential ambitions, Booker adopted a much harsher tone when talking about pharmaceutical companies. He appeared with Sanders at a press conference in January where he assailed corporate greed. He has also suggested he would, if elected president, take away companies’ intellectual property rights if they raise prices to an excessive level.

“This is one of the reasons why, well before I was running for president, I said I would not take contributions from pharma companies, not take contributions from corporate PACs or pharma executives, because they are part of this problem,” Booker said during the Democratic primary debate on June 26.

Trump’s presidential campaign contended that Booker’s stance was hypocritical given the past donations the senator had received from big pharma.

FACT: Cory Booker has accepted over $400,000 from the pharmaceutical industry during his political career. pic.twitter.com/1HUfFVBGVU

— Trump War Room (@TrumpWarRoom) June 27, 2019

While Booker’s performance during the debate resulted in a boost in campaign donations, his campaign announced it was returning a $2,800 contribution from Eagle Pharmaceutical executive vice president and chief compliance officer Michael Cordera, ABC News reported.

In the first quarter, Booker raised over $5 million, well behind many of his rivals. He has yet to disclose his second-quarter fundraising totals, and the reporting deadline is July 15.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: