On Capitol Hill, Republicans resist new voting protections

WASHINGTON — Even as Democrats seek to make it easier for people to vote, Republicans have uniformly resisted such measures, seeing them as a threat to their political dominance. The countervailing forces were evident on Tuesday during a House Committee on the Judiciary hearing titled “History and Enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

That law, which struck down racist barriers to voting across the South, put states where segregation had been practiced under strict federal oversight. But as the legacy of segregation has receded, resistance to that oversight has grown. That resistance was significantly bolstered in 2013, by the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder. That ruling removed the crucial “pre-clearance” requirement of the Voting Rights Act, which forced states to check with Washington before making changes to how they conducted elections.

Since then, 23 states have enacted measures — whether related to the locations of polling sites or to the presentation of identification in order to cast a vote — that have made it more difficult for people of color and the poor to participate in the democratic process, according to a 2018 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

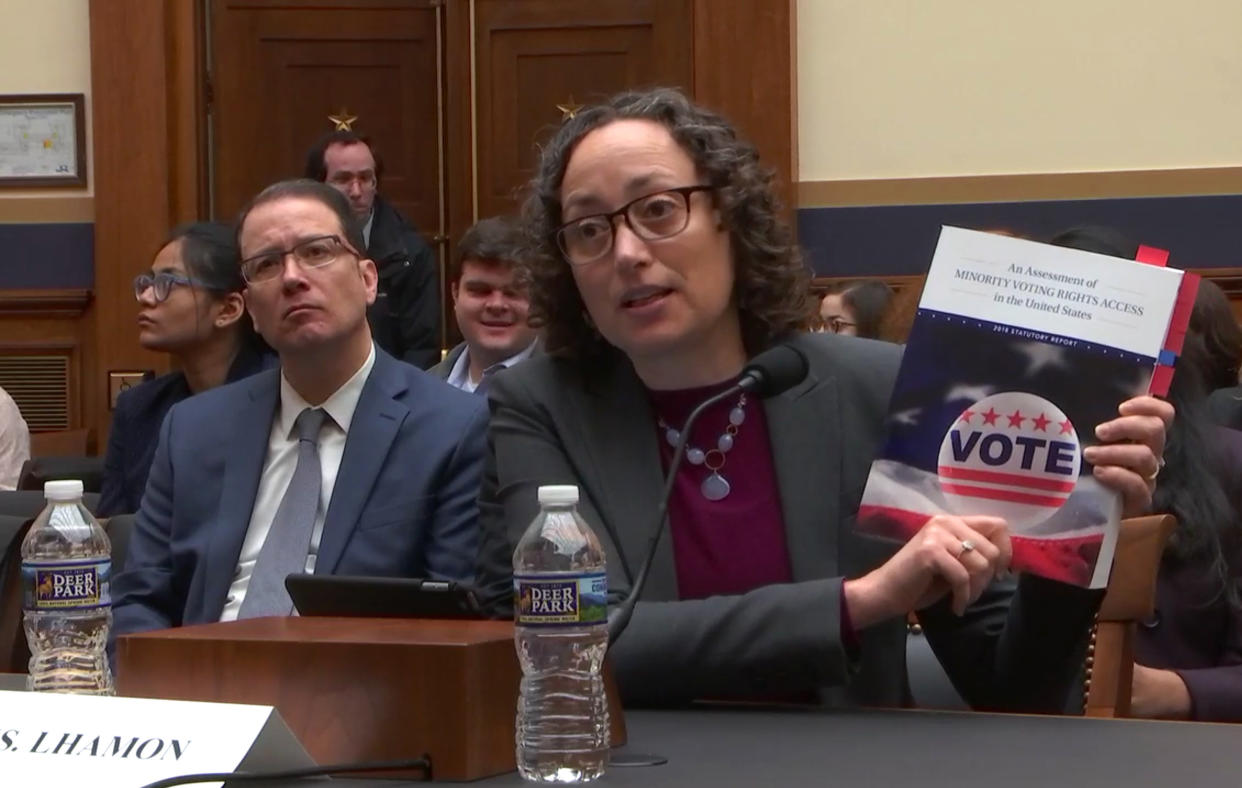

Speaking at Tuesday’s hearing, the commission’s chair, Catherine Lhamon, argued that voting rights were being eroded nationwide. “Race discrimination in voting is pernicious,” she warned, “and endures today.” She noted, also, that such discrimination can manifest in an “astonishing variety of ways.” During the 2018 election, for example, North Dakota enacted a requirement for voters to have a residential address, thus potentially disenfranchising Native Americans who live on reservations without house addresses.

Lhamon called the rollback of voter protections “bleak.”

That conviction is increasingly shared by Democrats. In her response to President Trump’s 2019 State of the Union address, former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams outlined a progressive agenda, but then warned that “none of these ambitions are possible without the bedrock guarantee of our right to vote.” She went on to say that “voter suppression is real. From making it harder to register and stay on the rolls to moving and closing polling places to rejecting lawful ballots, we can no longer ignore these threats to democracy.”

Some Democrats maintain that her Republican rival, Georgia secretary of state Brian Kemp, won the election by making it more difficult for as many as 53,000 people — many of them people of color — to vote.

Democrats in the House recently passed the For the People Act of 2019, which among other measures would make Election Day a federal holiday and implement automatic voter registration. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has characterized the legislation as a Democratic power grab; it stands no chance in a chamber he controls.

The Voting Rights Act remains the bedrock of modern civil rights legislation (along, of course, with the Civil Rights Act itself), and Democrats are eager to restore it to its previous stature. Speaking earlier this month on CBS’s “Face the Nation,” Sen. Doug Jones, D-Ala., said he wanted to “put some teeth back in the Voting Rights Act.” He alluded to a Senate bill, the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019, which would restore some of the authority taken away by the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision.

“We need to be expanding the voter rolls,” Jones urged. Critics like McConnell believe that any such expansion would exclusively benefit Democrats.

During the House hearing on Tuesday, Democrats cast the issue in moral and historical terms, as opposed to purely legislative ones. Steve Cohen, D-Tenn., chairman of the Judiciary’s Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties subcommittee, opened the hearing with a paean to Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., an ally of Martin Luther King Jr. and one of the surviving heroes of the civil rights movement.

“It would be a crime if this Congress did not pass another Voting Rights Act,” Cohen said. “It’s not enough to go to Selma with John Lewis,” he added, referencing the King-led march that began in that Alabama town in 1965. Lewis, then 25, was viciously beaten by state troopers at the beginning of the march, whose destination was the state capital, Montgomery.

“You need to vote with John Lewis,” Cohen urged in his opening remarks. “And you need to respect his opinion, his work — his life’s work — and pass the Voting Rights Act.” Such a law would reinstate and update protections of the original 1965 legislation, which have been eroded over the years, and not only in the Deep South states for which that law was originally intended.

While Republicans paid some lip service to overcoming the legacy of racism, they depicted the issue as resolved, and so far in the past that there was little left to do on the issue. Instead, they tried to focus on President Trump’s claims of electoral fraud, even though such instances are statistically irrelevant.

Trump has continued to make groundless claims of voter fraud during the 2016 presidential election, claiming that millions voted illegally for Hillary Clinton. No widespread fraudulent activity has ever been uncovered.

The hearing took a bizarre turn near the end when Rep. Louie Gohmert, R-Texas, who arrived just as the proceedings were about to end, asked for his turn to question the witnesses. Gohmert began by calling the Voting Rights Act — as it was reauthorized in 2006 — “unconstitutional,” an opinion he said he formed after speaking with “deans from some very liberal law schools.”

Gohmert then took to discussing the 2016 Democratic National Convention, where he said there were “huge barriers, fences” that he was able to see in photographs of the convention floor. He said he noticed that in 2008, “no one was allowed in the convention without proper identification.”

He then asked one of the witnesses if she was aware of any lawsuits pertaining to the DNC requirements, or perhaps to the security measures he appears to have seen. The witness, an expert in voting rights, said that she had not.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Women divided by race over key issues, but with areas of overlap

Maverick Republican William Weld looks to run against Trump's 'malignant narcissism'

The Army's killer drones: How a secretive special ops unit decimated ISIS

The Soviets wanted to infiltrate the Reagan camp. So, the CIA recruited a businessman to bait them.