Here's what you can expect now that the FCC has killed net neutrality

The Federal Communications Commission voted 3-2 Thursday to scrap all of its existing net-neutrality rules.

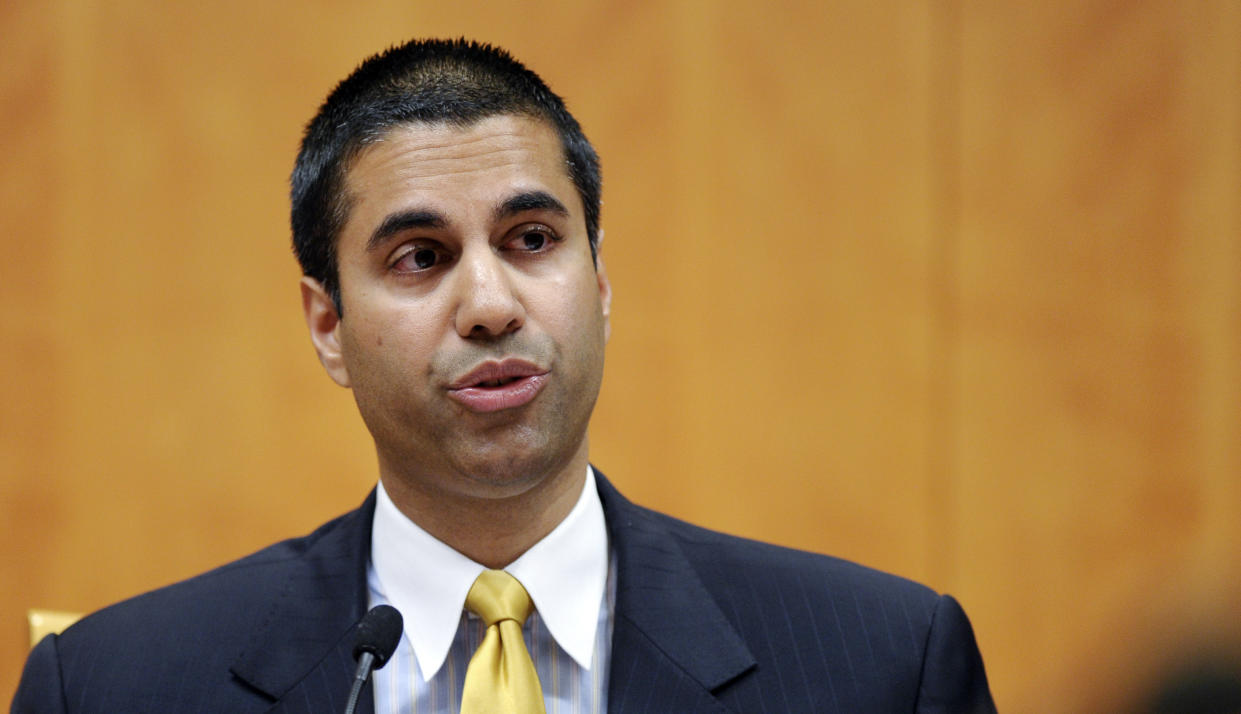

FCC chairman Ajit Pai has never wavered from his deep distaste for the rules adopted in 2015 that ban internet providers from blocking or slowing legal sites and forbid them from charging sites for priority delivery of their data.

His two Republican colleagues Mike O’Rielly and Brendan Carr agree with him, leaving Democratic commissioners Mignon Clyburn and Jessica Rosenworcel on the losing end.

So if you don’t like Pai’s plan, it’s too late to expect comments to the FCC to stop this. The chairman is so confident in his cause that he used his speech at the FCC Chairman’s dinner in Washington last Thursday to joke that, yes, he really was a Manchurian candidate for his former employer Verizon (VZ). (Verizon’s media division, Oath, includes Yahoo Finance.)

But what happens next may not go according to Pai’s script. Or yours.

The vote to kill net neutrality will first lead to protracted litigation. Should Pai’s plan survive that, internet providers will be free to block sites as long as they say they’ll do that. ISPs say they won’t (and there’s zero long-term business logic for them doing so), but this regulatory rollback will also enable them to engage in less-obvious mischief that the government may not be able to punish until years later.

It’s lawsuit time

Over the last decade of net-neutrality politics, only one group has consistently done well: telecom lawyers.

The FCC’s 2015 vote to put internet providers back under the same “telecommunications services” regulatory framework as phone companies appeared to have ended that legal trench warfare. The “Title II” rules that Pai calls “1930s-style” gave the FCC clear authority to create net-neutrality protections. Prior to that, attempts to craft weaker net-neutrality rules lost in court when judges found no solid legal foundation.

But Pai’s U-turn now invites challenges from advocates of the current rules. They can point to a law called the Administrative Procedure Act, which says an agency like the FCC can’t be arbitrary or capricious — meaning that the FCC of 2017 will have to explain why it disagrees so completely with the FCC of 2015.

“I think you’ll see public interest groups, trade associations and small and mid-sized tech companies filing the petitions for review,” predicted Gigi Sohn, who served as counselor for Pai’s predecessor Tom Wheeler.

Congress could also vote to stop this. But while polls show people hate this repeal — 83% opposed it in a new University of Maryland survey that took care to present Pai’s logic — Republican members have yet to show serious opposition.

Don’t expect any paid-prioritization deals anytime soon

But even if the FCC swiftly wins any court challenge, internet providers probably won’t block your favorite sites or demand they pay for fast-lane service. Why? Because the business model for that behavior seems doubtful.

“The major providers out there are smart enough to know not to get between their customers and their TV,” T-Mobile (TMUS) chief operating officer Mike Sievert said during a conference call after that carrier announced its plans to launch an online video service in 2018. “We’re not worried that we’re going to face throttling or prioritization issues.”

A critic of the current net-neutrality rules agreed, saying nobody needs priority delivery badly enough to pay for it.

“It’s going to take quite a while,”economist Hal Singer said. “You need a market for this stuff” — as in, an application that could work dramatically better with paid prioritization, such as live virtual reality. He rates the odds of such a deal happening in the next year at zero.

You could, however, see those abound once 5G wireless comes around in another two or three years. As analyst Peter Rysavy wrote in an April, 5G’s near-real-time responsiveness allows for use cases in which the developers of critical apps like autonomous-vehicle software would want to pay for priority handling.

Other kinds of mischief will be harder to see

Under Pai’s proposal, internet providers would be free to block, slow or surcharge sites as long as they said so upfront. If one went beyond that disclosure, the Federal Trade Commission could take action against the deceptive conduct — or against cases in which an internet provider abused its power to suppress a competing service.

But Pai would not make ISPs disclose these details in any standard format; the nutrition-label-style proposal of his predecessor Tom Wheeler is gone. An ISP wouldn’t even have to post the disclosure at its own site, instead letting the FCC publish it.

The FTC, meanwhile, could only take action after a violation had occurred. And its actions can take time: Its settlement with Vizio over allegations that it snooped on TV customers’ viewing habits landed three years after that alleged conduct began. The case the FTC opened against AT&T (T) for throttling the connections of wireless subscribers on its old unlimited plan starting in 2011 remains mired in litigation — which could wind up gutting the FTC’s oversight.

All this has led one tech investor who seemed less concerned about a net-neutrality rollback when it didn’t involve zeroing out the rules to worry about the lack of clarity startups might now face.

“My biggest worry if the FCC scraps all of the rules is that we enter an extended period of uncertainty,” said Proof co-founder John Backus. “We want to be able to understand the risk we are taking on, and weigh it against the possible upside. So the uncertainty here is a penalty to bandwidth-hungry startups.”

More from Rob:

You should still use the iPhone X’s Face ID even though hackers say they beat it

Barry Diller says big media will be ‘serfs on the land’ of tech giants

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.