Can we trust the cooking methods on the back of the bag?

We have an article on how to cook brown rice. Same goes for quinoa, for soba noodles, for lentils, and for beans—oh gosh, the beans!

But what's the point, when you can find the instructions on the back of the bag? Just as great recipes hide in plain sight in the grocery store, cooking techniques are listed on almost all bags of dry goods, and, in many cases, they're very carefully formulated—scientifically tested, even.

How to Cook Perfect Brown Rice by Marian Bull

How to Make Fluffy Quinoa by Sarah Jampel

How to Cook Dried Beans by Marian Bull

How to Cook Soba Noodles by Lindsay-Jean Hard

Do these back-of-the-bag techniques do right by us? The answer is yes. But is there ever a reason to cross-reference, to turn to the internet or a cookbook and choose a different method? Also yes.

Skip to the results of our test here or, first, let us explain...

When formulating back-of-package techniques, manufacturers and distributors of pantry staples have to take a lot into account that we at Food52 (and other publications) do not.

First, there's word count—the mere fact that a package can only contain a certain number of words because of spatial constraints (and thank goodness for that).

RELATED: Creative ways to cook rice

Then, there's the issue of ensuring that the directions are approachable to a huge group of consumers. They have to be written so that they're as universal as possible—understood and easy-to-execute to people from different regions of the country (and the world!), with different skill levels and different stocks of kitchen equipment.

Photo by Bobbi Lin

At Goya, for example, they must take into account that many of their beans, rices, and other pantry staples are cooked differently in various countries. Recipe editor and tester Carey Yorio Neuman told me that Mexican consumers, for example, are less likely to soak their black beans because they prefer the pure black color that gets washed out with a soak. "We think of Goya," which employs many people from different countries, "as our own focus group," Carey said: "There's a ton of different nationalities under one roof just within our Jersey City company. We call our own employees in to see how they do it in their country and then we make sure it is within the method tested in our facilities."

In addition to geographic variance, companies must also consider a huge range of cooking abilities—"we need to make sure that the language we use is approachable to any person no matter what their skill level is," Carey explained—and available equipment. The end goal is a technique that's written in the simplest terms and involves utensils and equipment most people have in their homes.

At Bob's Red Mill, that means composing their on-the-bag instructions by researching techniques across the board, then finding the straightest-shooting method that doesn't significantly compromise quality.

"If we can deduce the simplest method," said Food Innovation Chef Sarah House, "that is what we'll go with. After we nail that down, we'll try soaking overnight, forcing (rapid boil for a minute or two, then a soaking period), etc., and then prep instructions for special equipment like slow cookers and pressure cookers. Unless one of those methods make a significantly superior product, we go with the most simple and straightforward preparation."

Bob's then uses their website—where words are free! and space is plenty! la la la!—to elaborate on special circumstances that might not make it onto the bag: "If you have a bag of cranberry beans that have been sitting in your pantry for two years, the cooking time is likely going to increase because the beans have continued to dry out. In that instance, a longer cooking time and maybe even an overnight soak will be helpful. We try to include this information on our online recipes and blog."

Photo by James Ransom

But accounting for all variables—that is, making sure the technique will more or less work on different burners, in pots that conduct heat differently, if someone forgot to rinse the rice the required number of times—is impossible, and no recipe, not even the simplest one, is foolproof. "We try to be general, not quite as precise—there's always some measure of variance," said Fernando Desa, Executive Chef of Research and Development at Goya. Giving a wider range of cooking time—like 1 to 1 1/2 hours, for example—is one way to give a person cooking at home an opportunity to correct for mistakes, but you may also run the risk of mushy beans.

Keeping in mind the challenges and constraints companies face when writing the methodology to put on the packages, we decided to put their techniques to the test. We made two pots of each ingredient, one using the process outlined on the back of the bag it came in, the other using the (often more complicated and verbose) Food52 method.

Could these simple, bare-bones methods stand up to the methods we at Food52 have dug up from cookbooks and magazines?

Brown Rice

The methods:

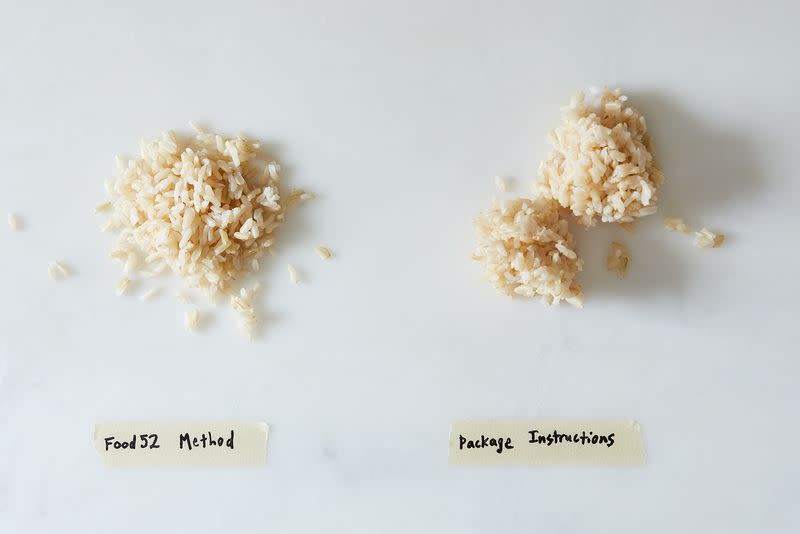

In the Food52 method, outlined here and credited to Saveur, 1 cup rice is rinsed under cold water until the water runs clear, about 30 seconds. It's then added to a pot of an excessive amount (12 cups!) of boiling water, along with 2 teaspoons of salt, stirred once, and cooked, uncovered, for 30 minutes. It's finally strained, added back to the pot, and covered for 10 minutes. Then the rice is fluffed.

In the package method, 1/2 cup rice goes into a pot with 1 cup of cold water and 1 1/2 teaspoons butter. Once the water boils, the rice is covered, the heat is lowered, and the grains simmer for 50 minutes. They're left alone for 10 minutes, then fluffed and salted.

The most independent grains there are versus a couple of clumps. Photo by Linda Xiao

The results:

The Food52/Saveur method produced grains that leaned towards al dente: separate, distinct, less gummy. The rice cooked according to the package was slightly mushier (as you can see: it clumped together when scooped from the pot). Kenzi Wilbur said "honestly, I would eat both" even though the Food52 method "does more justice to the rice's integrity, as odd as that might sound."

Black Beans

The methods:

The most major difference between the Food52 Method—originally from Cook's Illustrated and explained here—and the package method is the "salt brine."

In the Food52 method, a half-pound of black beans is mixed with 1 1/2 tablespoons of salt and covered with water. After 10 to 12 hours, the beans are drained, but not rinsed. They receive an additional teaspoon of salt, are covered with water by several inches. The water is brought to a boil, then reduced to a gentle simmer, and the beans cook, uncovered, for 45 minutes to 1 hour. They cool in their cooking liquid.

The back-of-bag method also calls for soaking the beans, but without the addition of salt. The beans are simmered (again, no salt) for longer: 1 to 1 1/2 hours. No instructions on cooling, so we decided to drain the beans right away.

Shiny and intact versus a little gritty and mushy. Photo by Linda Xiao

The results:

The Food52 beans won-out in appearance—shiny, pure black (perhaps because they weren't rinsed?), totally intact. And they were more flavorful, too. The package beans were mushier, grittier, and with a nothing-taste. That said, I'm sure they'd still be good mixed into rice (with a good sprinkling of salt!) or mashed up and re-fried. But I might not eat them in a salad.

Quinoa

Photo by James Ransom

The methods:

The Food52 Method, from this post is complicated: Soak quinoa for 5 minutes, rinse it, then toast it for 10 to 15 minutes. Then, for every 1 cup quinoa, add 1 1/4 cups water and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer, cover pot, and cook for 15 minutes. Drain the quinoa, return to the pan, lay a clean dish towel close to the surface, replace the lid on the pot, and allow to sit for 15 minutes.

The back-of-bag instructions skip the soaking, rinsing, and toasting. The quinoa is cooked, covered, but every 1 cup of dry quinoa gets 2 cups of liquid (as opposed to 1 1/4). The quinoa stands for 15 minutes, once being fluffed, in a covered pot for 15 minutes. No dish towel moisture-absorber.

All the fluff versus a bit of mush. Photo by Linda Xiao

The results:

You can see from the photograph that the Food52 method produced fluffier quinoa, delivering on its promise. The individual seeds remained intact and the flavor was earthy and nutty, more of quinoa (due to the toasting) than of salt. The quinoa cooked from the package directions was soggier, leaning toward mush, and the most pronounced flavor was the salt used to season it.

Soba

Be aggressive, be be aggressive! Photos by James Ransom

The methods:

In both methods, soba is added to boiling water (in the Food52 method, between 5 to 8 minutes; the package instructions give 8 minutes as the only time marker). The biggest difference, however, comes after the soba has cooked. In the F52 method, explained here, the soba is drained and dumped into a bowl of cold water (not an ice bath) and then rubbed, fairly aggressively. In the package method, the noodles are simply drained and rinsed with cold water.

The results:

Identical twin blobs. Photo by Linda Xiao

The Food52 noodles were firmer and less gummy. The package ones were softer and a little slimier, but our tester Olivia Bloom (also our Shop Editor and Executive Assistant) said the package-made noodles won out in terms of nuttiness and flavor, though the difference was "barely perceptible").

When Olivia tested the noodles with sesame oil and rice vinegar, the Food52 noodles held up better to the dressing due to their firmness.

In general, the Food52 methods are wordier and more complicated, and they require more thought, more equipment, more kitchen timers. But they also produced more Platonic pots of beans, rice, quinoa, and soba. If you're making one of these ingredients to eat on its own or as the foundation of a dish, it really might be worth taking the extra time (and the extra research) to draw out its flavor and cater to its textures as part of the cooking method.

The straightest-shooting, little-knowledge-needed directions on the package are bare bones, simple, and streamlined, without room to provide the detail or precision to produce the most perfect food of all time.

The whole quinoa set-up. Photo by James Ransom

But most of the differences were barely perceptible. And when differences were noticeable, it's not as if the grains or beans or noodles couldn't be very easily doctored (with dressings and cheeses and vegetables) or just eaten as-is, with the acceptance that not every bowl of quinoa has to be the absolute fluffiest.

And, as Sarah from Bob's Red Mill pointed out, these instructions—available to anyone who buys the package (or not), also make cooking more accessible: "When five people cook their beans a different way and some people can be very adamant about it, it can be overwhelming. When you're not experienced in the kitchen, it can be a deterrent. I like that we're making it approachable."

When do you make an ingredient according to package instructions and when do you go rogue? Tell us in the comments!