Amtrak train crash victim captures images before emotional collapse: ‘I was a wreck’

Ron Goulet remained composed for 10 hours after the train crash.

Then, in the dark of the June 27th night, away from the calamity, and alone at the Columbia hotel that Amtrak had secured, the 64-year-old Goulet began to cry, and cry some more.

“Blubbering,” Goulet said months later. “Blubbering — the trauma of the whole thing just finally came over me. I was operating in some other frame of mind, or adrenaline. Then it all came over me what I had been through.”

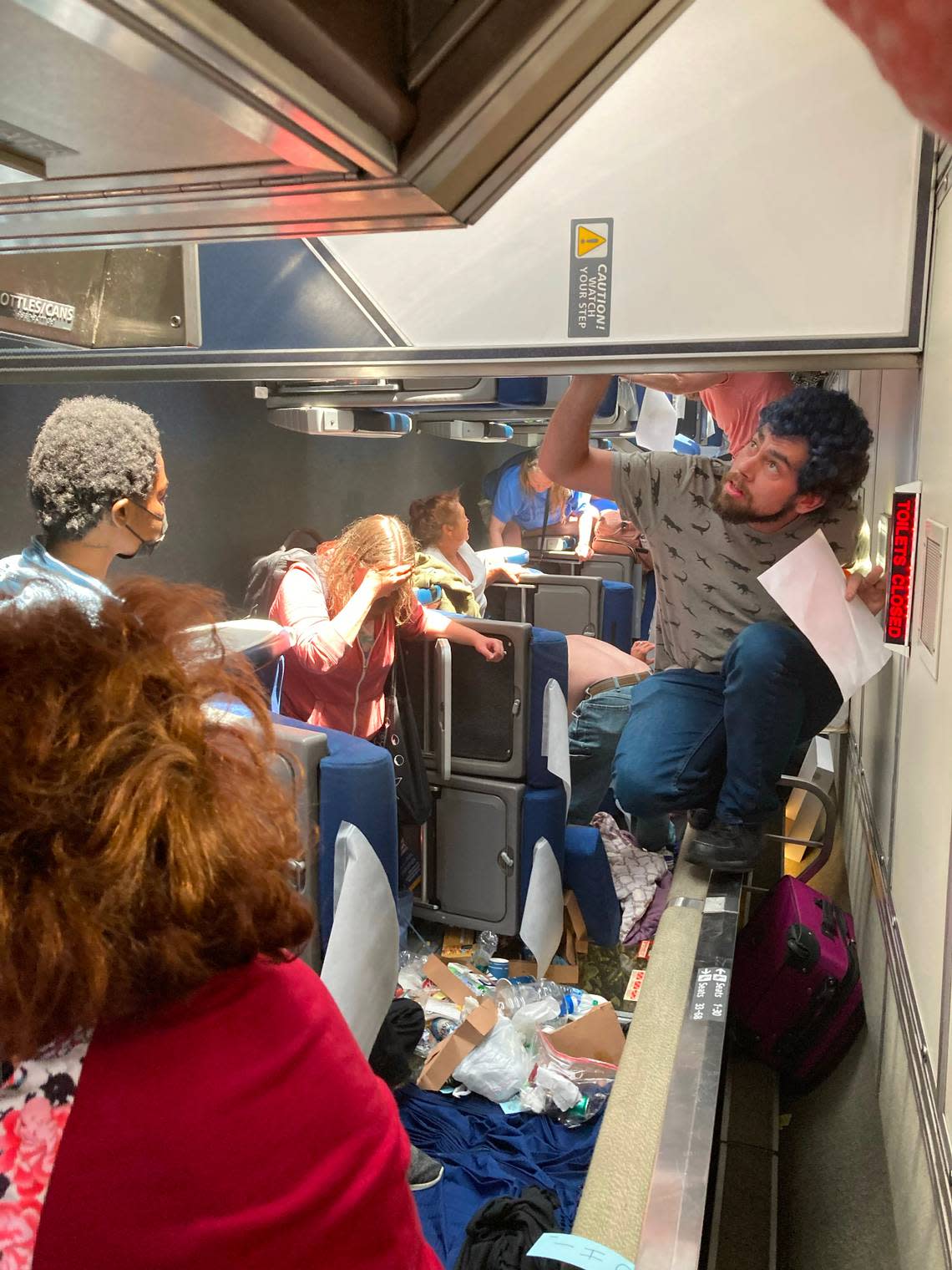

Flashes of those moments were captured on this cell phone — images from inside the train that, sent to and posted by a friend, appeared on news sites, zipped across the world even as the bodies of the four killed in the wreck were being removed.

“I cried pretty much anytime I talked about anything emotional for about the next three weeks,” Goulet said.

Having boarded Sunday morning where he lives in Flagstaff, Arizona, Goulet was already more than 24 hours into his trip when, at 12:42 p.m., the Southwest Chief — with its two diesel locomotives and eight cars wheeling at some 89 miles per hour — smashed into a dump truck that failed to get through a rural crossing just outside Mendon, Missouri.

For Goulet, it was supposed to be a lovely trip to see family, with a stop in Chicago, then another train to his boyhood home outside Toledo, Ohio, to visit his siblings and his 84-year-old mother, who had a heart scare last winter. His life had also changed drastically in the last eight years, when he decided to set aside 23 years of self-employment doing photography, graphic design and visual communications to go for steady work and benefits working the night shift on the manufacturing line for W.L. Gore, which makes GORE-TEX fabric and such.

Because he worked the late shift, he had grown accustomed to staying up all night, which is what he did before boarding in Flagstaff. He packed a pastrami sandwich, snacks and booked a $173 one-way coach seat on the upper level of a two-decker car.

He looked forward to the calm.

“With the airlines being so screwy, it’s the relaxing way to travel,” he said. “I didn’t want to deal with airports and flight cancellations and all that.”

But minutes before the Mendon impact, Goulet was already feeling agitated. The train, running three hours late, was also packed. Tons of people had gotten on in Kansas City. Amtrak made an announcement that the train would be overfilled. Every seat was taken.

Then, looking outside from his window seat, he saw the dump truck approaching, on a course to intersect the train.

“I didn’t know what kind of crossing there was, or anything,” Goulet said. “I could see we were coming up to a gravel road. There was an enormous amount of dust in the air.

“You couldn’t see what it was. … I distinctly remember thinking, ‘Well, I hope they stop.’”

Seconds later, the train lurched. Goulet could feel the impact through his seat.

“It was a thud,” he said. “I just remember feeling or realizing, ‘We hit something.’”

What happened in the next few seconds, Goulet said, felt like forever.

He was airborne.

“Like a dive, over the seat in front of me,” Goulet said.

He was already on the right side of the train as the train derailed and fell his way.

The right wall became the floor. The floor became the left wall. Bags and passengers crashed on top of him.

Sounds. Smells. Screaming. Crying. Blood. Goulet recalled none of that.

“At that point, I think I was so in my mind, my own situation, realizing, ‘OK, you’re OK,’” he said. He fell face flat; the people on top of him were scrambling to right themselves.

Physically, he didn’t feel injured, and wasn’t.

“I do remember realizing that it had stopped,” he said. “The entire event. ‘That’s over and this is the worst it was going to be.’ … Once everyone realized what happened, the scramble began. It was a lot more calm than I thought.”

In the end, Goulet would be among the last to leave the car.

A couple that had been across the aisle, but one row back, lay injured on the floor. The man had a massive bump on his head and was disoriented. The woman was in pain, having trouble breathing, maybe broken ribs and an arm.

Goulet didn’t know their names at that point.

They were Jim and Joann Coleman, she a seamstress and owner of Sew It Seems in Rockford, Illinois. When the Colemans boarded the train, Goulet had immediately noticed them and was annoyed because Joann Coleman was taking calls, doing business on her cell phone, too loud for his taste, and in speaker mode.

“I remember being very irritated,” he said.

But he stayed with the couple as others exited the windows that now pointed toward the sky.

“He was slow, he was woozy,” Goulet said of Jim Coleman.

Joann was in obvious pain. Neither could climb and would need to wait on first responders.

People, meanwhile, were walking atop the train, calling down, asking about anyone injured.

“Someone called down into the car, ‘What have you got!?’” Goulet recalled. “I referred to the lady (Joann Coleman) as ‘an elderly lady.’ She had a fit in a joking way. ‘Oh, so I’m elderly?!’

“She took two business calls even while she was injured, I swear.”

The Colemans, reached by phone in Illinois, said they were advised not to talk about their experience or injuries, at the advice of their attorney. But Joann Coleman confirmed Goulet’s telling of the story.

“I couldn’t climb out of the roof like everybody else,” she said. “I couldn’t do it. And so what else could I do?” She answered business calls.

Goulet stayed with the couple for 45 minutes or more, he said, until the medics came, snapping photos of people climbing out of the train.

He eventually followed. Only then, seeing the train laid out on its side in a crop field, did the enormity of the accident hit him.

“What I tell people is that it was like the end of some disaster movie, the final scene,” he said.

Helicopters hung overhead. Emergency vehicles, medics with backboards, seemed everywhere. He also thought back on images he’d seen of other derailments.

“I had no idea to what extent there were deaths or injuries,” he said. “I realized, you see these accidents sometimes where the train cars are all in a jumbled mess, like Tinker Toys. We were lucky this train kind of just fell on its side. We were going 87 miles per hour.”

He took pictures. “The old photojournalist kicked in,” he said. He sent them to a friend with media contacts. “I said get these out. … I remember not having a clue as to where we were.”

He spotted a sheriff’s deputy bearing a Chariton County patch on his shoulder.

“I don’t know Chariton County from Las Vegas,” he said. At a staging area, he climbed onto a school bus filled with passengers headed to a high school in Mendon.

“All these people looked like they had been through a war,” Goulet said.

At the high school, passengers were triaged — the back of their wrists marked in green, which is what Goulet got, if they felt they were OK. Red meant they would be seen at a hospital. As news of the accident broke, passengers’ cell phones lit up with friends, family and a flood of media requests for interviews.

Goulet spoke to CNN and CBS. He estimates he got more than 100 requests, including one to be on with CNN’s Don Lemon at 10:30 p.m. By then he had been transported to a Holiday Inn in Columbia.

That’s where the emotions overwhelmed him.

“Sometime in the middle of the evening, it all just came over me,” he said. “I’m done with this. I’m done. I don’t want to talk about it anymore. I never did get on (Don Lemon). I told them no.

“In the middle of that evening I was a wreck. I was a wreck talking to family on the telephone, figuring out where I should go, how I could get home. I was a wreck for a couple of days.”

The next morning, his brother drove from Columbus, Ohio, and picked Goulet up. With his luggage yet to be released, he bought new clothes at a Walmart, and went to Ohio to be with family.

He got his luggage four days later, and was reimbursed for every penny he spent on clothing, snacks, travel, including for the money his brother spent on gas driving from Ohio. Goulet knows that numerous passengers have entered into lawsuits against Amtrak and the railroad, which he understands and was still contemplating for himself.

He also knows that, at some point, he will get back on a train again.

“I’m not really terrified of the idea,” he said. But he’s not in a rush. Another trip to Ohio is in the offing.

“The plan,” he said, “is to fly.”