Alice Munro, Master of Short Story, Dies at 92

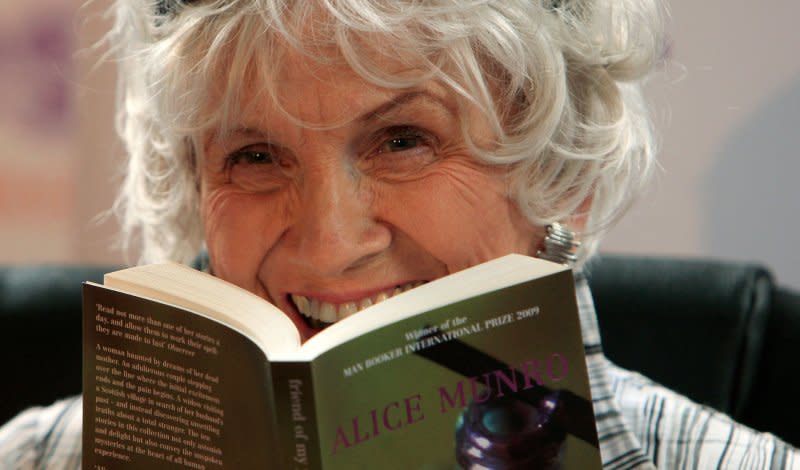

Author Alice Munro at home in Clinton, Ontario, Canada, 1994. Credit - Peter Sibbald—Redux

Alice Munro, the Nobel Prize-winning Canadian author who perfected the art of the contemporary short story, died on Monday, May 13, Penguin Random House Canada has confirmed. She was 92 years old.

In 14 short story collections, including The Beggar Maid; Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage; and Dear Life, the author captured the familiar quandaries and complications of everyday life. Children leave home and return to find it changed. Family units unravel when they are hit with unexpected and tremendous loss. Lovers become partners, then parents, then people they don’t quite recognize. Munro depicted these narratives with masterful levels of wit, humor, and care, and in doing so, challenged the tenets of fiction writing to showcase the power of the short story.

"Thank you, Alice Munro, for one glittering jewel of a story after another. Thank you for the many days and nights I spent lost in your work," Jane Smiley wrote in a tribute to the author in the Guardian in 2013. "Thank you for your unembarrassed woman's perspective on the lives of girls and women, but also the lives of boys and men. Thank you for your cruelty as well as your kindness, because the one plus the other is the essence of truthfulness."

Munro’s first book of short stories, Dance of the Happy Shades, was published in 1968 and received Canada’s Governor General Award for Literary Merit that year. In the decades that followed, Munro went on to win two additional Governor General Awards for Literary Merit. Her work was celebrated through a number of prizes, including a 1997 PEN/Malamud Award and a 2005 Medal of Honor for Literature from the U.S. National Arts Club. In 2009, she was awarded the Man Booker International Prize for her lifetime body of work. Four years later, Munro became the second Canadian author to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“There's a kind of tension that if I'm getting a story right I can feel right away, and I don't feel that when I try to write a novel,” Munro told the New York Times in 1986. “I kind of want a moment that's explosive, and I want everything gathered into that.''

Life in Canada

Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw on July 10, 1931 in Wingham, Ontario to Anne Clarke (née Chamney), a schoolteacher, and Robert Eric Laidlaw, a farmer. Munro’s father built their family home, a red-brick farmhouse flanked by trees on a country road, where he raised foxes and mink.

Much of Munro’s work is anchored in the towns of Western Ontario, giving readers glimpses into the author’s upbringing and family life. In the introduction to her 1996 collection, Selected Stories, Munro described why she loved to set her narratives in the areas of her youth: “I am intoxicated by this landscape, by the almost flat fields, the swamps, the hardwood bush, by the continental climate with its extravagant winters.”

Munro fell in love with reading as a young girl, and started writing poetry after she discovered Alfred Tennyson’s work. One of her favorite books was Wuthering Heights. By the time she was 14, Munro aspired to become a writer. “But back then you didn’t go around announcing something like that,” she told the New York Times in 2013.

When she wasn’t reading, Munro’s adolescence was spent tending to chores around the house as her father struggled with his business and her mother grappled with the symptoms of early onset Parkinson’s disease. She explores this time at the end of her last collection, Dear Life, through four narratives that she writes are “autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact.” In the revealing pieces, she reflects on growing up as her parents suffered financially and physically. “The strange thing is that I don’t remember that time as unhappy,” Munro wrote in the titular story in Dear Life. “There wasn’t a particularly depressing mood around the house. Maybe it was not understood then that my mother wouldn’t get any better, only worse.”

As a high school student, Munro’s passion for literature catapulted her to academic success. In 1949, she became her high school class valedictorian and she received a scholarship to study at the University of Western Ontario as a result of her achievements in English. But when the money from her scholarship ran out in 1951, Munro could no longer afford to stay enrolled. Instead of returning home, she married her first husband, James Munro, a history student from an upper-class family, whom she met at college.

James Munro was supportive of his wife’s ambitions as a writer. In 2006, Munro spoke to the Virginia Quarterly Review about starting out at a time when she did not know of many women who wanted to write professionally, and noted she was lucky to be married to a man who supported her career. “I was so fortunate that way,” she said. “Because I don’t know anybody else who would have wanted the wife to do something that took away from her ‘normal’ role—or might have been seen as competition.”

Finding the short story form

Alice and James Munro moved to Vancouver in 1951. Between 1953 and 1966, the couple had four daughters: Sheila, Catherine, Jenny and Andrea, although Catherine died shortly after she was born. While her husband went to work, Munro found pockets of time to write while caring for their children, which meant writing in short spurts during nap times and at odd hours of the day.

This, she explained to the Atlantic in 2001, contributed to her use of the short story form—she simply did not have the time to dedicate to writing a novel. “I couldn’t look ahead and say, this is going to take me a year, because I thought every moment something might happen that would take all time away from me.”

Though she likely didn’t know it then, those years Munro spent as a housewife and young mother would become guiding forces in her fiction. She would spin stories rooted in domestic drama, from daughters who didn’t understand their mothers to partners pulled apart due to their different upbringings. Munro also experienced her share of romantic strife—she and James Munro divorced in 1972. Four years later, she married geographer Gerald Fremlin, and it was then that her career finally started to take off.

Munro was 37 when her first short story collection was published in 1968. Dance of the Happy Shades won the most prestigious literary prize in Canada, the Governor’s General Award, and was a defining first step in building her reputation as an accomplished writer. She then published Lives of Girls and Women in 1971 and Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You in 1974.

In the late 1970s, Munro gained even wider acclaim through the publication of her stories in the New Yorker. In 1977, she published “Royal Beatings,” which centered on the complicated relationship between a young girl and her step-mother. A year later, the same story appeared in Munro’s collection Who Do You Think You Are? (published outside of Canada as The Beggar Maid), which followed the two women over several decades in 10 interconnected stories. The book received the 1978 Governor’s General Award and was nominated for the Booker Prize in 1980.

As more of Munro’s stories were published in the New Yorker, her prominence as a writer grew. She crafted narratives on realistic female characters and their relationships with growing up, growing old, and the losses that accompany entering different stages of life. These themes are often the backbones of lengthy novels, but Munro was able to render her characters’ struggles in aching specificity in just a single story.

In the 1980s, Munro began debuting stories and books with greater frequency. Her stories appeared in the pages of the Paris Review, the Atlantic Monthly, and more. As the years passed, Munro continued writing books of short stories to critical acclaim. Each built on the momentum of the last, culminating in Munro’s last five collections in the 2000s that comprise what could be considered her best work.

In novelist Jonathan Franzen’s New York Times review of Munro’s 2004 collection, Runaway, he wrote that Munro kept writing the same story, with the same fundamental elements of love, loss, and dislocation, but was able to reveal more about the human condition with each one. “Reading Munro puts me in that state of quiet reflection in which I think about my own life: about the decisions I’ve made, the things I’ve done and haven’t done, the kind of person I am, the prospect of death.”

Her lasting legacy

In 2013, Munro won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Typically, the prize is awarded to novelists, but Munro’s win further elevated the power of the short story form. The award capped off her massive contribution to how authors think about the architecture of a story, and she was quick to acknowledge the importance of the win for the genre she nearly perfected. She told Nobel Media after accepting her prize that she hoped it would help raise the status of the short story for all authors—advancing the form beyond what many writers work on before they launch their careers as novelists.

Her devotion to the short story structure has influenced some of the most celebrated contemporary fiction writers. Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri told the New Yorker that Munro’s work felt revolutionary for her: “She taught me that a short story can do anything. She turned the form on its head. She inspired me to probe deeper, to knock down walls.”

Kristin Cochrane, CEO of Penguin Random House Canada, which has long published Munro’s work under its McClelland & Stewart imprint, responded to news of her death in a statement: “Alice Munro is a national treasure—a writer of enormous depth, empathy, and humanity whose work is read, admired, and cherished by readers throughout Canada and around the world,” she said. “Alice’s writing inspired countless writers too, and her work leaves an indelible mark on our literary landscape.”

After winning the Nobel Prize, Munro continued living a quiet life in Canada. She had announced her retirement from writing a few months before winning the Nobel Prize—and remained true to her word. Dear Life, published in 2012, was her last collection. When discussing her retirement with the National Post in June of 2013, editor Mark Medley remarked that her fans would be disappointed. Munro responded in her typical, forthright fashion: “Well, tell them to go read the old ones over again. There’s lots of them.”

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com.