How Alabama’s victory in the 1926 Rose Bowl paved the way for Southern football dominance

There was a time when the nation regarded football in Alabama — in all of the South, really — as unworthy of notice, much less respect. Eastern legacy colleges, monstrous Midwest institutions, growing Pacific coast universities had mastered this new sport of football, the unholy offspring of soccer, rugby and a street fight. The South? The South was too busy trying to climb out of a post-Civil War hole to focus on anything as frivolous as football. The condescending verdict on the South: like war, industry, race relations and education, football was just one more province where the South fell short.

Then came the 1926 Rose Bowl, and nothing about college football in the South — or anywhere else in the country — would ever be the same again.

Every college football game carries symbolic and narrative weight, and some even rise to the level of epics. Think, say, the old Notre Dame-Miami “Catholics vs. Convicts” battle — the players aren’t just representing their schools, they’re easy stand-ins for an entire worldview.

But few college football games have borne the weight of an entire region the way the 1926 Rose Bowl did. The Civil War still lived on in the memory of older Southerners, and the stories of the war — undoubtedly embellished and sanitized to present a very specific image of Southern history — were part of the region’s everyday vernacular and self-image. Beyond that, though, the South labored under the weight of its own irrelevance and disrespect — some self-inflicted, some perpetuated by the rest of the nation — and any chance to claw back a little self-esteem was a welcome one.

Pregame: The boys from ‘Tusca-loser’

The NCAA recognizes college football champions dating back to 1869. Most Southern schools began playing in the late 1890s — Alabama’s program started in 1892 — and by the 1920s, college football had grown popular enough that the idea of conferences was taking hold.

With the active support of university president Mike Denny — for whom Bryant-Denny Stadium is in part named — Alabama’s football program strengthened in the early 1920s. By the 1925 season, head coach Wallace Wade led the Tide to a 9-0 regular-season record.

Back then, the Rose Bowl was the only postseason game; not only were there no playoffs, there were no alternative or second-tier bowls. It was Rose or bust. The game pitted regular-season champions from both coasts, and in 1925, the champion of the Pacific Coast Conference — the predecessor to the Pac-12 — was Washington. The “Purple Tornado,” a nickname Washington really ought to bring back, posted nine undefeated seasons in a row from 1908 to 1916.

The Tide’s undefeated record didn’t impress the sportswriters and coaches of the day. (Sound familiar?) But after yet another college-football-is-too-professional controversy led Dartmouth, Michigan, Colgate and Princeton to decline invitations to the postseason game, No. 4-ranked Alabama should have been the next up.

Even then, the Rose Bowl committee fought the idea. “I’ve never heard of Alabama as a football team,” one committee member scoffed, “and I can’t take a chance on mixing a lemon with a rose.” The desperate committee finally got over its biases and invited Alabama four weeks before the game.

"In those days, Alabama, or the Southern teams, weren't noted for great football potential," Alabama halfback and future Western movie star Johnny Mack Brown said in 1969. "But it seems like they thought perhaps we were lazy, full of hookworms or something of that sort.”

Few outside the South gave Alabama even a prayer of a chance. Washington had dominated its opposition all season, shutting out six of its 10 opponents, allowing no more than 14 points in any game, and winning its first three games by a total of 223-0.

Outside commentators, meanwhile, gleefully piled on the Tide. Famed humorist Will Rogers, presaging message boards by decades, dismissed the Tide’s hometown as “Tusca-loser.” One sportswriter picked Washington to win by 51 points. Another said the Huskies would “blow the Crimson Tide back across the continent as a pale pink stream.”

All the while, Alabama booster Champ Pickens was engineering a telegram campaign imploring the Tide to fight for the honor of their region. Community leaders back in Tuscaloosa came right out and said that the honor of the Confederacy now fell to the Crimson Tide, and it was up to them to avenge the losses of the Civil War.

“Alabama’s glory is in your hands,” Alabama Gov. William W. Brandon told the team, as recounted in the book “The Sporting World of the Modern South.” “May each member of your team turn his face to the sun-kissed hills of Alabama and fight like hell as did your sires in bygone days.”

“By the time they get [to Pasadena], they’re not just the University of Alabama football team,” Alabama historian and Auburn professor emeritus Wayne Flynt said in “Roses of Crimson,” a 1997 Alabama public television documentary about the 1926 Rose Bowl. “They are the South’s football team, and they are sort of reliving the sectionalism of 100 years of competition between North and South.”

"Southern football is not recognized or respected,” Wade said in his pregame speech. “Boys, here's your chance to change that forever.”

The Game: A furious comeback

The first half seemed to codify the nation’s early impressions of both teams. Washington leaped out to a 12-0 lead and had little trouble containing Alabama on both sides of the ball.

At halftime, Wade walked into the locker room, looked at his battered players, and uttered one simple line: “And they told me that boys from the South would fight.” That was all he said, and all he needed to say.

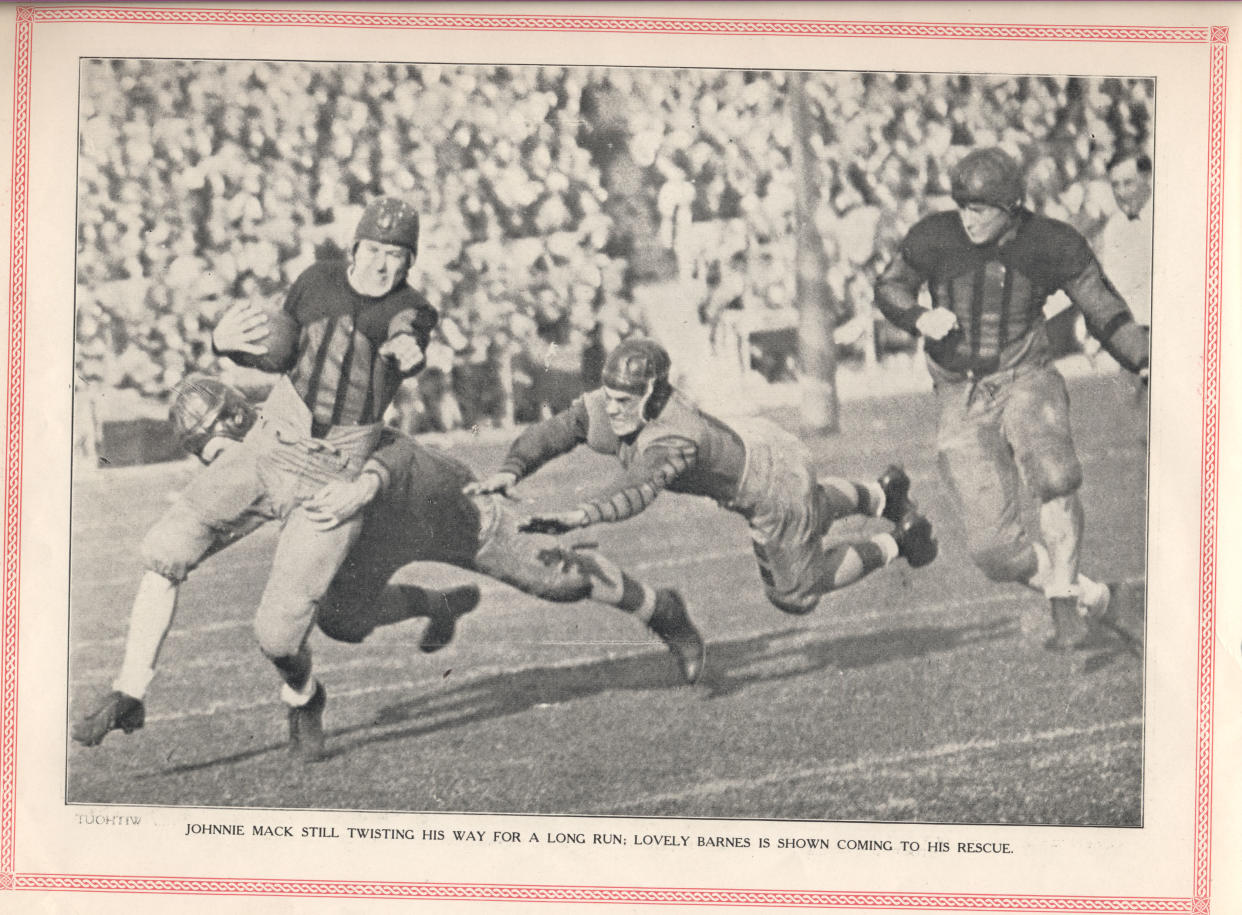

The Tide roared out of the locker room and immediately scored to close the gap to 12-7. On their next possession, Johnny Mack Brown reeled in a 59-yard touchdown and, soon afterward, another 30-yard touchdown reception. The total: three touchdowns in seven minutes of game clock and a 20-12 lead.

“The third period will go down as the greatest chapter Alabama has ever written in the Book of Football,” Birmingham News reporter Zipp Newman wrote in his account of the game. “A beaten team came back via the road of determination and cold grid tactics. Alabama threw the Huskies into hysterics. They were helpless to stop the outburst of the Tide that hurled giants like splinters into the air.” (Sportswriting was very different in 1926.)

A late Washington touchdown wasn’t enough to close the gap, and Alabama claimed its first national championship. Washington head coach Enoch Bradshaw was so incensed he left the field without shaking Wade’s hand.

"It was as if Southerners had proven something that the South had been trying to prove ever since the Civil War — that we were as good as anybody else," Flynt said. "Given a level playing field, and the same number of players on the field, that we could go out there and beat anybody, even the best that the country could possibly produce."

Important caveat to this entire story: Both teams — just like every major college team in the country — were all-white. Integration was years, in some cases decades, in the future. Alabama football famously didn’t embrace integration until after an integrated Southern Cal team stomped Bryant’s all-white Crimson Tide team in 1970. (There’s more than a little suspicion that Bryant helped engineer that meeting to impress upon Tide fans the necessity of integration; if they refused to acknowledge the morality of it, at least they could understand the competitive advantage.)

Alabama’s 1926 train trip back across the country became one long celebration. At a stop in New Orleans, a thousand locals met the train at the station to praise the Tide. Red and white flags accompanied Alabama all the way back to Tuscaloosa, and Alabama’s governor praised the team at a massive celebration there. The South had a win at long last, and Alabama had a line (“Remember the Rose Bowl!”) for its fight song.

The Aftermath: A new era of Southern football

It would be a stretch to say that the 1926 Rose Bowl was responsible for the rise of Southern football; the social, cultural and economic shifts that turned the South into a 1960s behemoth and a 2000s juggernaut took time to develop. But that Rose Bowl upended perceptions of Southern football. No longer could the Harvards, Michigans and Princetons of the college football world assume that the South couldn’t compete at their level. Alabama, for instance, would play in five more Rose Bowls over the next 20 years, winning three, losing one and tying one.

Not only that, the Rose Bowl gave the South reason to believe that it could compete on a national level. It would be decades before the South would produce more than the occasional national champion (Alabama, Georgia Tech, TCU, Texas A&M), but once Auburn won the title in 1957 and Bear Bryant took over Alabama in 1958, Southern schools began claiming at least shares of the national title every few years. By the 1990s, as the rise of Florida State, Miami, Tennessee and Florida gave way to Alabama, Auburn, LSU and Georgia, the South’s college football preeminence was both complete and unquestioned.

Alabama faces Michigan on New Year’s Day in the Rose Bowl, and if Washington can get past Texas, the national championship could be a rematch of 1926. That game would be watched by millions more people than the first meeting, but it can’t possibly have the same impact as that long-ago game in Pasadena.