Adidas, Ye, and the death of DEI: A cautionary tale for corporate America

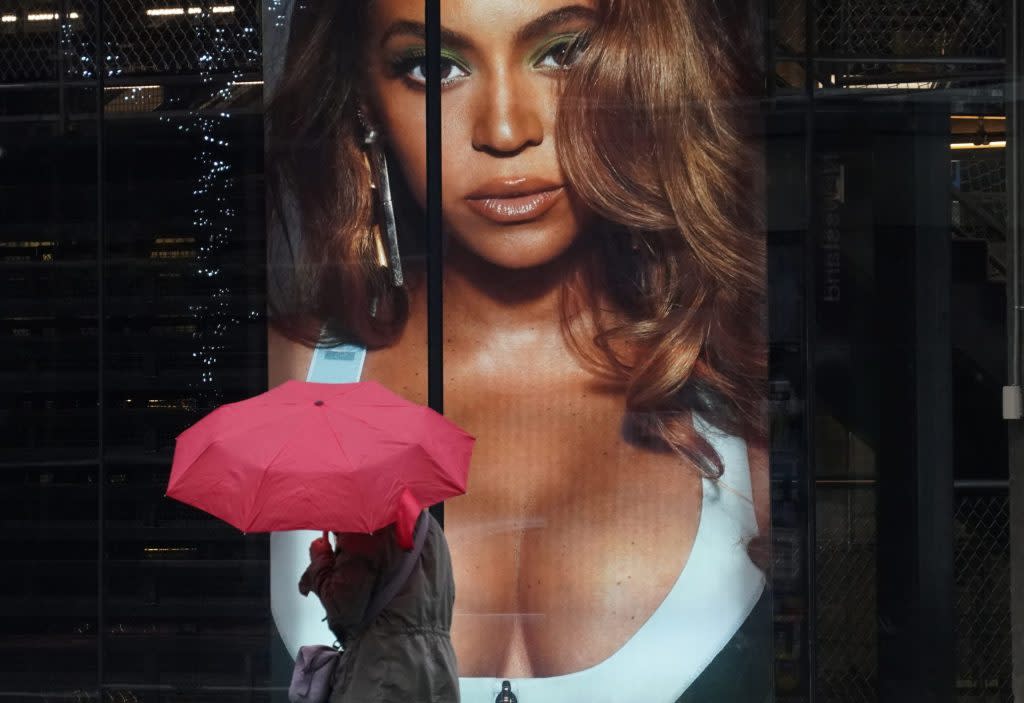

Watching the home-video clips of Beyoncé as a child, interspersed with glimpses of young girls of color stretching to hit the high notes in the pop star’s “All Night,” it’s hard not to feel chills. The Adidas “Impossible Is Nothing” ad campaign (the title a quote from legendary boxer Muhammad Ali) delivers an irresistibly inspiring message, showing the world how a determined and talented Black girl from Houston reinvented herself as a global icon.

Adidas is known for projecting this progressive, scrappy optimism in its marketing campaigns, with Black success stories often driving the narrative, and Black athletes, models, artists, and celebrities carrying the message. But former and current employees at the German company say that despite this public narrative of Black empowerment, Black professionals within the corporation are rarely able to penetrate the top strata of leadership—or to feel comfortable when they do.

They describe a cascade of slights and microaggressions at the 74-year-old athletic-wear giant that have marginalized their perspectives. As one former Adidas executive who is Black put it: “Internally, there was a cap on how far you could go.”

Adidas is far from the only company that has been criticized for leadership ranks dominated by white men. But the brand’s showcasing of Black culture and bodies in its marketing—including most notably its ill-fated alliance with rapper, producer, and designer Ye (formerly known as Kanye West)—has often shoved its corporate diversity struggles into the spotlight.

Lately, former and current Black leaders at the company tell Fortune, things have gotten worse: Since the beginning of 2023, 10 Black and brown executives at the VP level and above—many hired in the U.S. in 2020 and 2021 during the reckoning in corporate America following the murder of George Floyd—have been pushed out or quit, Fortune has learned. At least eight other Black executives in key roles in the U.S. have also departed since 2020.

A spokesperson for the company didn’t dispute these numbers but said “the rate of departures among Black executives was either lower or comparable to that of other groups.” Adidas declined to disclose, however, how many roles at the VP level and above are held by Black executives or other underrepresented groups and would not share any other data about executive departures.

Sources say the loss of so many high-level people of color—which included seven in the U.S.—has been significant, and a visible blow to diversity efforts at the company. To put this in context: Sources tell Fortune that Adidas’s leadership ranks include an estimated 275 leaders at the VP level and above, with approximately 55 roles in the U.S. among them (numbers that roughly align with public data available on LinkedIn). Of those, there were nine Black vice presidents or above at Adidas North America before the departures—so the seven Black executives at that level who have left since early 2023 made a significant dent. Sources also point to the withering of a diversity-focused committee formed in 2020, whose members have largely left the company.

Among the sources Fortune spoke to for this article were 12 former and current Adidas managers and executives who requested anonymity, fearing that revealing their identity would jeopardize their jobs and future employment opportunities. (For Black executives, several people said, talking to the press about racism in the workplace presents a conundrum: The same anti-Black biases and stereotypes that they hope to erode by shining light on their experiences also prevent them from speaking on the record, for fear of being labeled as angry or bitter.)

The Adidas spokeswoman pointed to improvement in the company’s overall diversity numbers, and said the company remains dedicated to meeting its diversity goals. Regarding how former and current employees who spoke to Fortune depict the company’s culture, she wrote in an email: “We vehemently disagree with these views as they do not accurately reflect the reality of our company or the sentiments of our current employees.”

Indeed, there can be no one definitive narrative of a company’s culture, especially that of a $43 billion multinational brand: Every employee’s experience is their own. Still, the picture of being a Black executive at Adidas that emerges from these interviews raises important questions about who is empowered to lead at the company, and why. And it can serve as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of taking a superficial approach that pays lip service to diversity—without doing the work.

The Adidas-Yeezy meltdown’s unseen effect

It’s impossible to talk about diversity at Adidas without considering its biggest success of the past decade—which turned into its most spectacular public relations disaster. The story of the Yeezy line, and Adidas’s falling out with its cocreator, Ye, that’s familiar to most, happened in 2022: the messy, embarrassing, financially devastating breakup of the German shoe giant and the American superstar after he took to social media to say he was about to go “death con 3 on JEWISH PEOPLE.” (Presumably, he meant Defcon 3, the military term suggesting readiness for a full assault.)

Less well known is a backstory that Black Adidas employees haven’t been able to forget: They say they lodged complaints about Ye’s anti-Black statements years earlier, but they were ignored—and that his public anti-Semitic comments were taken far more seriously than the anti-Black comments he made in the press. (The company also reportedly ignored a slew of Ye’s comments made in private that offended various groups, including Jewish employees.)

The first significant crack in Adidas’s relationship with Ye appeared in May of 2018. That’s when the celebrity was interviewed on the Hollywood news site TMZ and suggested that America’s history of slavery could be blamed on enslaved people. “When you hear about slavery for 400 years. For 400 years? That sounds like a choice,” he told the stunned TMZ anchors.

The incident was a red flag for Adidas employees working on Ye’s Yeezy sneaker line, a team that was mostly Black and brown within a corporate arm that was predominantly white. The team requested a meeting with top leadership to discuss Ye’s offensive remark and other problematic behavior. Across Adidas, Black employees spoke with their managers, who ran their concerns up the chain.

Bimma Williams, a former marketer for the Yeezy line, later described the Yeezy team meeting—in which he said he went “toe to toe” with leadership about Ye’s comments—on a Complex podcast. “My question was, How can you expect me to show up to work and give all that I give to this team,” he recalled, “if we don’t feel like the values that we carry are represented here—and you’re not saying anything about it?

“I have to know you care about what it is that I am as a human in order for me to feel like I care about hitting these numbers,” he continued. “My experience started to deteriorate from there, because I just couldn’t really get an understanding from the brand, what the brand stands for.” (Williams did not respond to a request for further comment.)

2018 was a precarious moment in Ye’s partnership with the brand: Adidas was building hype for the three-year-old Yeezy line with small, sporadic releases—or “drops” in the parlance of sneakerheads—a strategy to juice demand. And behind the scenes, the company was betting big on the collab, ramping up production of Yeezy’s distinctive, genre-busting sneakers. Being tied to the artist gave Adidas a fighting chance in its long-fought battle for market share against Nike’s Jordan brand, the label that had dominated sneakerhead culture and defined cool for Black and Latino customers since Michael Jordan chose Nike over Adidas to launch his market-changing shoe line in the 1980s.

In response to internal calls to “do something” about Ye, then-CEO Kasper Rørsted, a white European, “silenced us,” said one ex-employee, who is Black and asked to remain anonymous because she still works in the field. Some Black Adidas workers wanted the company to cut ties with Ye, she explained, while others asked that the company at least denounce Ye’s slavery comments publicly. Rørsted responded to these requests with vague promises to speak with the celebrity about the issue, then reminded workers how much the company was making from the Yeezy deal, said the former worker. The suggestion, the employee said, was that the company would “crumble in on itself” if it dropped Ye. “There was never a direct response,” she said. And there were no repercussions.

Following the TMZ interview, Adidas’s leadership team discussed options for responding, the Wall Street Journal later reported, but ultimately chose to forge ahead with the partnership. Rørsted declined to comment for this story, but in 2018, he appeared on Bloomberg TV and said, “There clearly are some comments we can’t support.” But when asked if there had been internal conversations at Adidas about dropping Ye, the CEO responded, simply, “No.” “Kanye has helped us have a great comeback in the U.S.,” Rørsted told CNBC after the TMZ debacle.

When the Yeezy collaboration collapsed four years later, following Ye’s “death con” tweet, a Black senior executive recalls a white executive saying: “It’s really getting bad now because the Jews are upset, and in America, Jews have all the power. So we have to deal with this.” That was the day that particular executive decided to leave, they told Fortune: “Something inside of me died.”

Ye, who has spoken openly about his mental health issues, eventually apologized for the “death con 3” rant and has said he regretted his earlier outburst about slavery. But the uproar he caused with his anti-Semitism in 2022 made continuing his contract a nonstarter for the German firm—even though the collaboration delivered an estimated 40% of the company’s profits at that point. (Ye did not respond to multiple requests for comment via his Yeezy fashion line or other avenues. Adidas declined to comment on the split, saying that the company had terminated the Yeezy partnership and it had “nothing to add” to previous statements.)

Adidas was not the only company to part ways with Ye during the volatile period following his anti-Semitic tweets. Fashion retailer the Gap and Balenciaga both ended their relationships with the musician in late 2022. But for Adidas, the breakup with Ye and his sneaker brand was a public relations and financial disaster that left the company with 1.2 billion euros ($1.3 billion) worth of unsold inventory in various stages of development. In 2022, Yeezy shoes were on track to bring in $1.7 billion and instead fell half a billion short of that.

Arguably, this could all have been avoided if Adidas’s leaders had only listened to the Black employees who raised the alarm in 2018. So why didn’t they? The fact that Yeezy was already a promising moneymaker is part of the answer. But former executives at the company say the brand’s limp reaction to the concerns of the Yeezy team in 2018 was indicative of larger problems.

“I do think the bottom line was a factor,” one former top executive who is Black told Fortune, referring to the company’s decision to not drop Ye after his slavery-was-a-choice comment. “I also think it was a factor that it was a majority Black and brown team, and he was a Black man.” When Ye behaved badly, this person said, the implied message from white leadership was, “Okay, Black people, that’s your guy.” Complaints about Ye from Adidas’s Black employees were dismissable, in other words.

In the aftermath of the Yeezy breakup, it emerged that the sneaker maker had tolerated bizarre and offensive behavior from Ye for years. From early on, the star had asked employees to watch porn as a creativity-boosting exercise, the New York Times reported. He had reportedly forced one woman of color on the design team to sit on the floor during a meeting because she “didn’t deserve a seat at the table,” according to Rolling Stone. He drew swastikas on sneakers and was prone to fits of rage. Members of the Yeezy team experienced verbal abuse, burnout, and low morale, and many quit their jobs.

When Adidas eventually canceled Ye’s partnership over his public comments about Jews (reportedly a decision top management ultimately reached in a two-minute phone call), “that was a difficult conversation internally,” said a former employee, who is Black.

“Black employees at that moment couldn’t understand why Adidas turned their back [on them] years prior when Ye made the controversial remarks about Black people and slavery.”

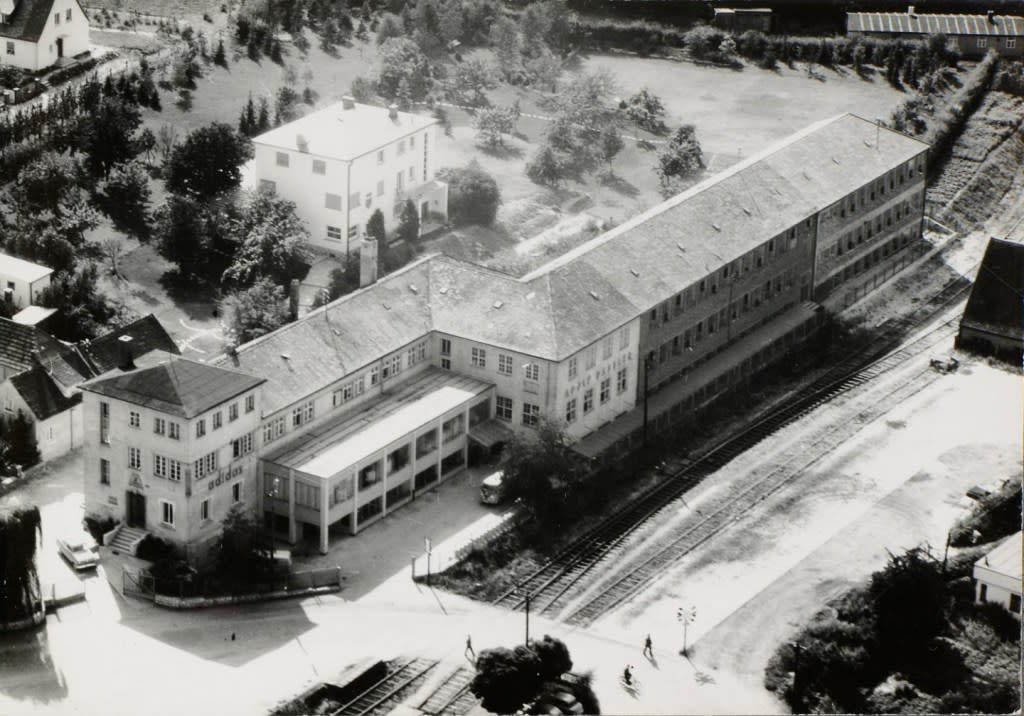

Roots in rural Bavaria

Black former Adidas employees who spoke to Fortune about the disconnect between the brand’s marketing image and its internal lack of diversity invariably returned to two topics: corporate culture and Herzogenaurach, Germany, the rural town in Bavaria where the company is headquartered. Adidas’s culture is rather bureaucratic and top-down, employees say. Major decisions about faraway markets are made in Herzogenaurach, hardly a world—or even a European—cultural capital.

The town, which data from the government show is largely German and white, is known as the birthplace of brothers Adolf “Adi” and Rudolf “Rudi” Dassler, whose sibling rivalry split the family shoe company and gave the world the competing athletic apparel giants Adidas and Puma. But past employees say that the town’s tainted lore—like many German business leaders of the 1930s, both brothers joined the Nazi party—adds to the HQ’s “weird” vibe. Expats who are not white and European can find it a particularly lonely place to visit or live. One former Adidas executive said working in “Herzo” as a Black person made them feel like “a giraffe on roller skates.”

Another former senior executive wondered, “If you want the best of the best talent from a global perspective, why would you ask them to move to a farm?”

A former category director, who is Black, recalled one particularly telling incident during a trip to Adidas’s head office last spring. Her mission was to wow its global product leaders, who were all white, with a presentation about her unit’s planned clothing line, she said. The former director recalls navigating the campus with a group of her mostly Black and brown colleagues the day she arrived.

Dragging duffel bags and rolling racks of clothing, they approached the Adidas mothership, a modern and striking glass and concrete building held aloft by steel pillars. “Everybody was just staring at us,” she said. Then, at a corporate fete following her successful presentation, a white peer from Germany approached her: “Oh man,” he said. “I saw you guys walking across campus, and I thought you were rappers that Adidas hired for our meeting!”

That comment solidified her resolve to leave after several years at the company, she said. It also told her that little had changed since she attended a sales meeting in Los Angeles a few years before. There, she said, images of Black athletes and models flashed on huge screens, and uncensored rap music filled the room. “The N-word was on rotation,” she recalled, yet in a crowd of 700 employees, she counted only 20 who were Black.

Promises to change

Former Adidas workers say the retailer’s DEI efforts largely felt like window dressing before and after the post–George Floyd cataclysm in corporate America in 2020. Already, the New York Times had reported that in 2018, fewer than 5% of the 1,700 employees at Adidas’s North American headquarters in Portland, Ore., identified as Black. Globally, about 1% of the company’s vice presidents were Black, according to sources who spoke with the Times. The company’s “reckoning” over diversity, equity, and inclusion at Adidas in 2020 was particularly bitter.

That summer, employees protested with remote walkouts and adamant social media posts. Following internal investigations, the global head of HR lost her job for reportedly calling diversity efforts “noise.” A longtime executive board member was investigated after it was revealed he’d referred to a Black regional leader as a “contribution to diversity” at a meeting of 200 managers. (After a lengthy inquiry into that incident and others, the board member resigned last year.)

In 2020, following the weeks-long, often public, confrontation between Black employees and the company’s top leadership team, Adidas made several pledges to repair ties and rebuild its diversity efforts. In response to the work and research of a group of 12 high-level Black employees who had created a coalition advocating for DEI across Adidas, the company promised that Black and Latino people would fill at least 30% of all new job openings in the U.S. and earmarked $120 million for scholarships to support Black students over five years.

The promises fell short of the asks made by the coalition—which became a working group known as United Against Racism and came to include several white executive sponsors—but it was a start.

Today, however, ex-employees say that little has improved at Adidas over the past four years, and, if anything, there has been a “rewinding” of DEI progress under Bjørn Gulden, who became CEO in 2023. Soon after his appointment, Gulden commented to senior staff that DEI was a waste of time and that employees should get back to caring about profits, according to a former executive who said they were in the room. Gulden declined to comment for this article, but an Adidas spokesperson denied that Gulden made these statements and said they do not reflect his attitude.

Broadly, the discussion of corporate diversity efforts in 2024 is quite different from that of 2020: Following the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision prohibiting the use of race-based affirmative action in college decisions, an emboldened conservative anti-DEI movement is operating at full tilt in the U.S., and many companies have scaled down or walked back their DEI commitments. A string of high-profile chief diversity officers have also left their posts or seen their functions rolled into other jobs.

At Adidas, seven of the 12 original Black executives who had organized in 2020 have left the company, and all five of the white executives who initially joined United Against Racism are gone. Just this month, the company announced that two additional high-level roles in the U.S. were being reorganized, and the Black executives holding those jobs would leave.

A current employee who is Black said the news left many feeling “shook.” “These were real genuine people that we looked up to and have connected with on the side,” says this person. “And just to see that they were quote-unquote leaving or being let go was a huge, huge red flag in the direction of the organization.” Even so, this employee said that they were still hopeful Adidas could get back on track “in terms of creating a place that values diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

In corporate statements, Adidas said that its commitment to DEI hasn’t wavered. An Adidas spokesperson said the company remains dedicated to filling 30% of corporate roles with Black and Latino candidates and devotes “significant resources” to building “meaningful connections with candidates from these underrepresented communities,” while following best practices for inclusive hiring and retention.

Adidas pledged in 2020 that by 2025, Black and Latinx employees would represent 20% to 23% of corporate roles, of which 12% would be leadership jobs, defined as roles at the director level and above. At the time, employees from those racial groups held 12% and 7% of these roles, respectively. At the end of 2023, it had made good progress toward those goals: Black and Latinx employees represented 18% of corporate roles and 10% of leadership positions. The company declined, however, to disclose how many senior leadership roles exist in the U.S., nor would it share retention rates.

Retention is the key problem, said one current employee: “Any progress that we make is temporary progress,” they said, adding that the company pays more attention to hiring enough people to “say that we’re making a difference” but rarely talks about keeping Black and Latinx employees in leadership roles. “I think that’s the loophole in this whole thing,” they said.

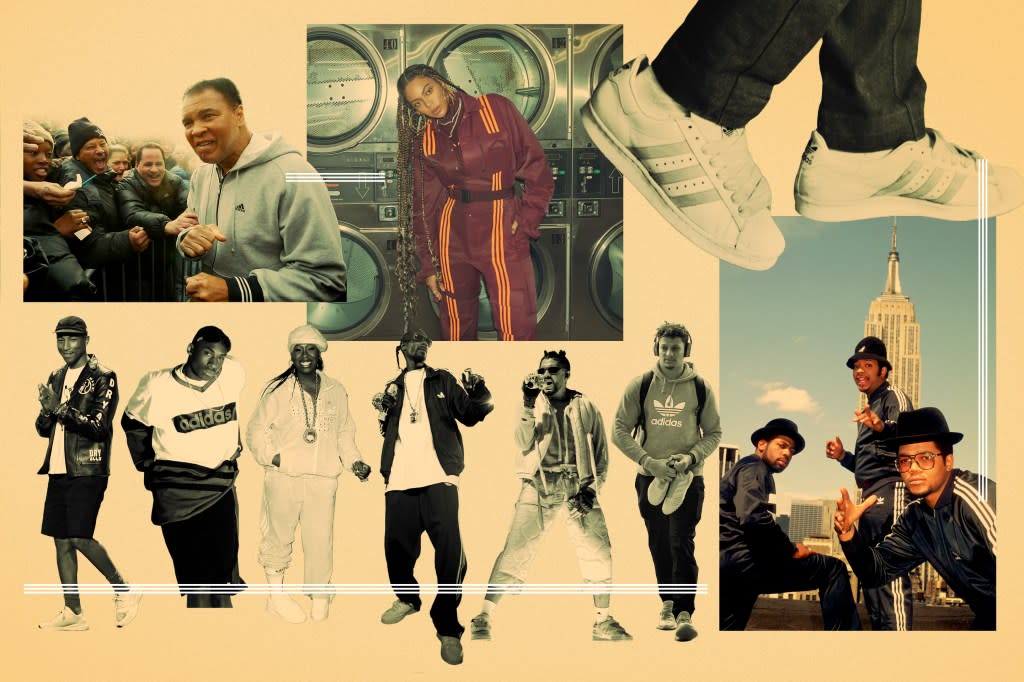

Black celebrities gave Adidas its cool factor

The 74-year-old German firm has a complex relationship with American Black culture. While Black athletes such as the boxers Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier wore Adidas in the 1970s, it was the rise of the hip-hop era in the late 1980s that truly catapulted the brand into the realm of cultural significance. The enduring track “My Adidas” by rap trio Run-DMC marked a turning point, helping Adidas’s three stripes and trefoil logo become symbols of Black culture and streetwear fashion.

The brand’s celebrity collaborations and endorsements include people of various races, but Black creators and athletes are prominently featured. The rappers Missy Elliott and Snoop Dogg each created lines with Adidas in the aughts and 2010s, respectively. More recently, Adidas collaborated with Beyoncé and her Ivy Park label, musician Pharrell and Humanrace, fashion designer Jerry Lorenzo and Fear of God, and, of course, Ye. (Representatives for Beyoncé, Pharrell, and Lorenzo didn’t respond to requests for comment.) Adidas also sponsors many athletes, including James Harden, Derrick Rose, and Patrick Mahomes.

The disconnect between this marketing approach and the internal demographics of the company was striking to Black employees, several told Fortune. “If you look at all the ads, it’s brown bodies everywhere—muscular, wet, looking powerful and strong,” said one former executive who is Black.

Another ex-executive, who is also Black and was one of the original members of the coalition, said he pushed Adidas to avoid photographing mostly Black male athletes and models with bare chests, a practice he saw as implying white ownership over Black bodies. The coalition also persuaded the company to stop using “urban” as a euphemism for “Black.” (Adidas told Fortune that this account was “inaccurate” but declined to elaborate.)

A former director-level employee who worked with one of Adidas’s Black celebrity partners said they saw a cravenly transactional approach. “So we’re going to make a billion dollars off of this person,” the employee said of the company’s attitude, as she perceived it. “But when it comes to getting to know them, and what drives them, and what inspires them, that they could care less about.”

An internal movement withers

The inferno that the Black Lives Matter resurgence sparked in 2020 has since dwindled. “I don’t think Adidas understands African American culture. And I think they’re fearful of it because of what happened in 2020,” a former senior executive said. Corporate promises to reflect on Adidas’s history and systemic racism were quickly forgotten, said another: Rather than dig in to understand Black consumers and the disconnect internally, the company pointed to the work of United Against Racism to create a veneer of accountability.

Meanwhile, many of those who joined the coalition have since left the company. Indignities accumulated, and by 2021, some Black employees had begun to observe a backlash to the measures put in place after the summer of 2020. When Adidas mandated companywide diversity and sensitivity training, it sparked pushback from some white managers who saw it as a useless distraction, according to several past senior employees.

Lauren Body, a former global category director at Adidas who was part of the coalition, remembers herself being skeptical of diversity training at the time and worried it would be performative. Body, who is Black, said purposeful educational seminars are useful, but that they’re often “surface level.” Inclusion lessons, she said, fail to root out insidious habits such as overlooking employees of color for stretch assignments and promotions. “We can tick a box that said we read the module. Great. But what else is the company doing?” she asks. “Leaders around the brand have taken the training, but what have they learned?”

United Against Racism no longer exists as a group of employees, but its former members can claim some wins. The company created a team that oversees its engagement with Black and Latino populations, and other groups, and its investments in entrepreneurs of color. Two basketball executives in the coalition also played a role in persuading Adidas to move its basketball division to Los Angeles from Portland, which is among the whitest of big American cities. Several former employees who spoke to Fortune also noted that, even before the George Floyd protests, the company had partnered with Pharrell and Pensole Design Academy to launch a shoe design school for young women of color. And through its "Honoring Black Excellence" philanthropic program, the company has given $1.7 million to nonprofits supporting Black athletes and communities.

Still, by 2021, Black employees remained frustrated—and an exodus began. Some felt that being among the 2020 dissenters put a target on their backs, marking them as “difficult people,” said one white former executive who was a member of the coalition. (An Adidas spokesperson said “Our company does not label employees based on their participation in initiatives like the 2020 coalition. We value diversity of opinions and encourage open dialogue.”) Others said that even once a Black executive was promoted to a higher title, their perspective was not trusted. The sense was, “Shut up and be happy you’re in the room,” one former Black executive recalls.

Adidas hired some people of color as key leaders. Few lasted long. Vicky Free, a former BET executive who became the first female global head of marketing and first Black woman in that role at Adidas, stayed for two years. Amanda Rajkumar, the former global head of human resources and the first woman of color on Adidas’s executive board, quit in 2023, after starting in 2021. The executive board is now entirely white, while two women of color, including the African American former Olympic track and field star Jackie Joyner-Kersee, sit on the company’s supervisory board. Rupert Campbell, the U.K.-born former head of North America and the first Black manager to hold the role, gave his notice to Adidas late last year. He spent less than two years in Portland after a 2022 transfer from Russia.

The executives hired to replace Campbell and Rajkumar are both white. A white European man is also in charge of global marketing, a former employee explains, though he doesn’t hold Free’s previous title. (Asked about this, Adidas explained to Fortune, “Our selection process focuses on appointing the most qualified candidates based on their qualifications and experience.")

According to a past employee, many leaders of color were “micro-aggressed out the door” by their superiors and board members—an assessment shared by other former workers. Gulden moved a recently created head of diversity role from the global head office to Portland and added an HR remit to the position, diluting the role’s focus on DEI. He said diversity wasn’t an issue in Europe, according to a former executive. (The company denied that Gulden made this statement, writing that it does not “reflect his attitude or the reality of the company.”) One senior executive who is Black recalls being asked by a board member, “Why do Black men like to shoot people?”

Even in the current climate of DEI backlash, the common-sense business case for diversity remains strong—with younger workers listing it as a priority and research showing that diverse teams make measurably smarter decisions that lead to higher profits and revenue. The loss of diverse talent, and the perception of Adidas as a DEI laggard, could be a significant liability for Adidas. David Swartz, a Morningstar analyst, pointed out that sporting goods companies like Adidas and Nike often face financial and reputational disasters due to decisions made by top leaders, who largely remain white men. Nike, for example, was embroiled in a PR crisis for firing women athletes when they became pregnant. “You wonder, is that because the executives are white men and they're looking at all this, as ‘We want these people to drive sales of shoes and clothing,’ rather than considering ‘What does this do to our image with our customers?’” Swartz asks, highlighting the potential risks for Adidas.

“It's not ‘Kumbaya, let's all hold hands,” said one Adidas alum about the need for sporting goods companies to diversify their workforces. “This is a business imperative, and you will suffer if you don’t understand the values of your consumer, and the moment that we're in.”

Coiya Wilson, a former project manager in brand marketing at Adidas, said companies should also recognize the basic moral case for honoring the communities whose cultures they tap into.

“If you're talking about Black people, and we're your target,” said Wilson, who was one of two Black women in the United Against Racism coalition, “then the people internally should represent the people you’re targeting externally.”

The after-effects of a breakup

Black employees still feel betrayed by how Adidas responded to their alarm at Ye’s anti-Black racism, former workers say. And the fallout from the company’s relationship with the musician continues to play out uncomfortably and under the harsh gaze of public scrutiny.

A group of investors who bought Adidas shares between 2018 and early 2023 has filed a class-action lawsuit claiming that Adidas misled shareholders by not disclosing the risks connected to Ye’s behavior. The company knew as far back as 2018 that employees were rattled by Ye’s slavery remarks and other behavioral issues, the investors say. In a company statement to Fortune, Adidas said “We outright reject these unfounded claims and will take all necessary measures to vigorously defend ourselves against them.”

Though a tough pill to swallow, in retrospect, Adidas’s continuation of its relationship with Ye holds some financial logic: Even after the rapper’s 2018 TMZ outburst, Yeezy sales at Adidas climbed to over $1 billion the following year. (Ye received a 15% cut of all sales.) The half billion dollars in lost sales the year of the breakup sounds devastating, except when compared with the $6 billion in total revenue that has been attributed to Yeezy sales in press accounts (some citing analyst estimates) since the partnership began. Even since it collapsed, Adidas has made hundreds of millions selling Yeezys that were already in the pipeline, though it said it’s donating a portion of the proceeds to anti-hate groups. Ye is also still earning a share of sales.

Gulden, a designated turnaround CEO poached from Puma, has made progress shoring up the company’s share price, which is up 30% over the past year, though still depressed compared to 2021 when Yeezy sales and other market forces lifted it to record highs. As for diversity and inclusion, the new administration has made some public missteps.

Recently, while Adidas was still reeling from losing its contract with the German National soccer team to Nike, which will take over as the team’s sponsor from 2027, a scandal broke: The font used on that team’s jersey made the number 44 look remarkably like the “SS” logo for Schutzstaffel, a former Nazi paramilitary group. The company had to ban fans from personalizing official league jerseys with that number. (Adidas noted in an email that the design of the numbers is managed by the German Football Association, independently of Adidas.)

Some employees have worried that Gulden might explore a renewed partnership with Ye: Last September, the CEO set off alarm bells within Adidas when he said on a sports podcast that he didn’t think Ye meant what he said about Jews. A public and internal backlash forced the CEO to walk back the comment.

Then, in mid-February, Ye posted an Instagram photo of himself sitting next to Gulden at a Los Angeles airport. At first, the musician said in a caption that he had “bumped into” Gulden after the Super Bowl and floated a Yeezy distribution deal with him. (Gulden publicly denied any plans for resuming the partnership.)

Ye then changed the caption to “Make Adidas Great Again”—before ultimately deleting everything.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com