Adapt or Die: Motorsports' Knife-Edge Push to Go Electric

IndyCar was born at the 1911 Indianapolis 500, and for more than a century, the series has been a crucible for innovation. Early aerodynamics, ferociously turbocharged Offenhauser engines, mid-mounted V-8s in spidery little fuel-filled cigars—IndyCar has a long history as a dangerous laboratory, and the planned 2024 introduction of a supercapacitor-based hybrid powertrain seems a reasonable next step in that long tradition. But it was very nearly a fatal stumble.

This story originally appeared in Volume 20 of Road & Track.

The series had been using a 2.2-liter twin-turbo V-6 engine formula since 2012, an eternity in racing circles. At the 2018 Indy 500, IndyCar announced an updated set of regulations that would bring a new 2.4-liter twin-turbo V-6 for 2021. The press release that announced the move carried no mention of hybridization, and, as expected, the new formula with its extra 200 cc of capacity was panned for a lack of imagination and relevance. No new engine suppliers signed on to join stalwarts Chevrolet and Honda. A do-over was needed, and quick.

Worse, according to the story in the IndyCar paddock, Honda made it known that without some degree of electrification finding its way into the series, in short order, it would be unable to justify the corporate marketing and promotions spend for its ongoing participation. Honda’s days in the series could be numbered.

The 2019 Indy 500 brought a new announcement: IndyCar would be going hybrid. But a year had been lost while coming to that necessary realization. The debut for the new power units was pushed back to 2022. Then the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the launch of the new hybrid powertrain to 2023.

Important names like Hyundai, Porsche, and Toyota met with the series and expressed interest in its turn toward hybridization, but talks stalled in every instance. Although the nature of the energy-recovery-system (ERS) side of the equation was still a mystery, Chevy and Honda went ahead and built brand-new 2.4-liter engines in preparation.

After receiving a wide array of proposals, IndyCar chose Mahle, the renowned piston maker and e-mobility vendor, to produce its spec ERS units. Yet the project was plagued with issues from the outset. As the end of 2022 approached, it became clear the series would not be going hybrid in 2023, or anytime soon. Here, the series’s engine partners made a radical call.

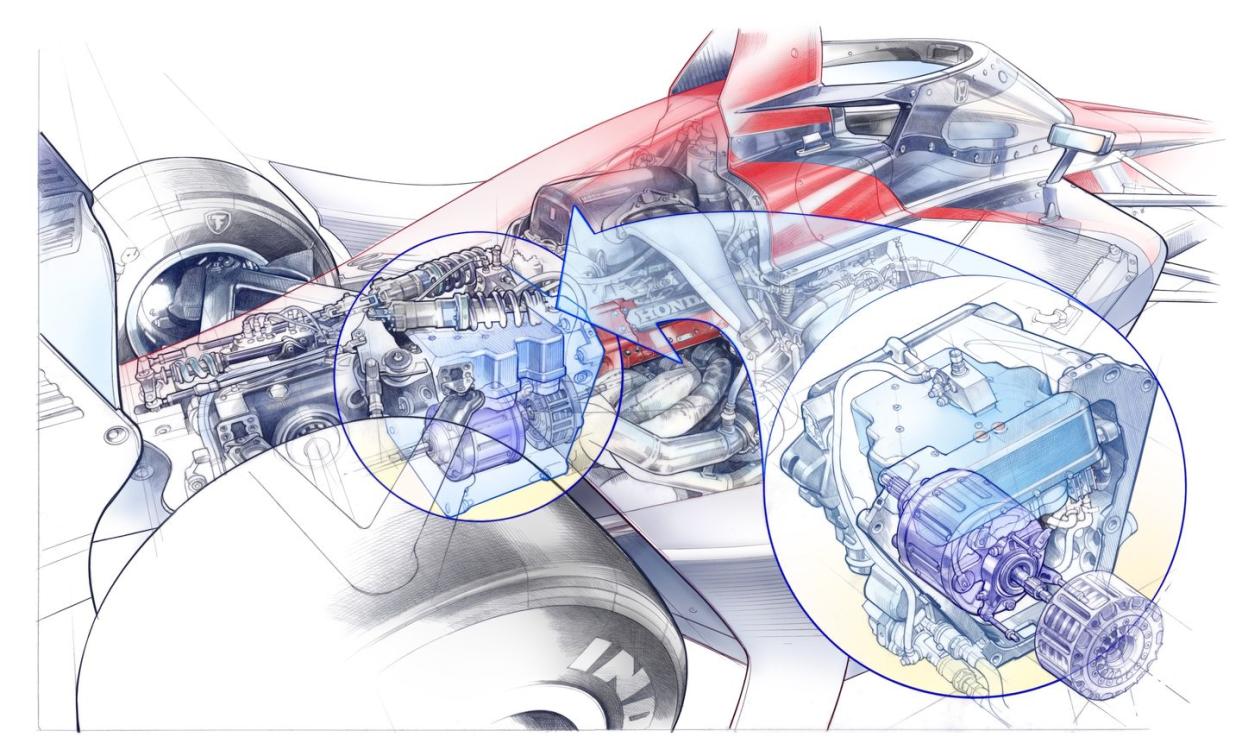

Scrambling to prevent IndyCar from failing in its hybridization mission and losing one of its only two manufacturers, Chevy and Honda offered to abandon their 2.4-liter engine programs, commit those sizable budgets to creating a joint-venture ERS design, and share the costs of mass-producing the units for IndyCar.

In a surprising turn, warring opponents called a truce to save IndyCar. Together, they’re creating the very ERS units—Chevrolet is leading the motor-generator project, and Honda is overseeing the supercapacitor side—that they’ll attach to those aging 2.2-liter engines, which turn 13 years old in 2024. Once development is done, the cease-fire is off, and Honda and Chevrolet will use these new electrified powerplants to molly-whop each other for the rest of the decade.

We’ve sung our devotionals to fuel and compression and spark since the days of brick-and-board tracks. Our tribe was defined by internal combustion, and we knew its soul by the sounds fired through headers and exhaust pipes. They ticked. Purred. Raged.

This was the covenant for the first 100 or so years of motor racing. But time moves on. What’s a racing engine in 2023? There’s no longer a single, simple answer.

As the auto industry progressively trades gas pumps for charging stations, most corners of the motorsport world have adapted. That’s a good thing. The fact that most racing series cannot agree on a single choice of powerplant shouldn’t be perceived as a problem; it’s a gift with an open-ended future.

“Not so long ago, we weren’t sure what we’d be racing with. But right now, it’s super exciting because racing is being used for what racing is really good at, which is agile development, fast development, making things smaller, lighter, more powerful, through different solutions,” says Honda Performance Development president David Salters.

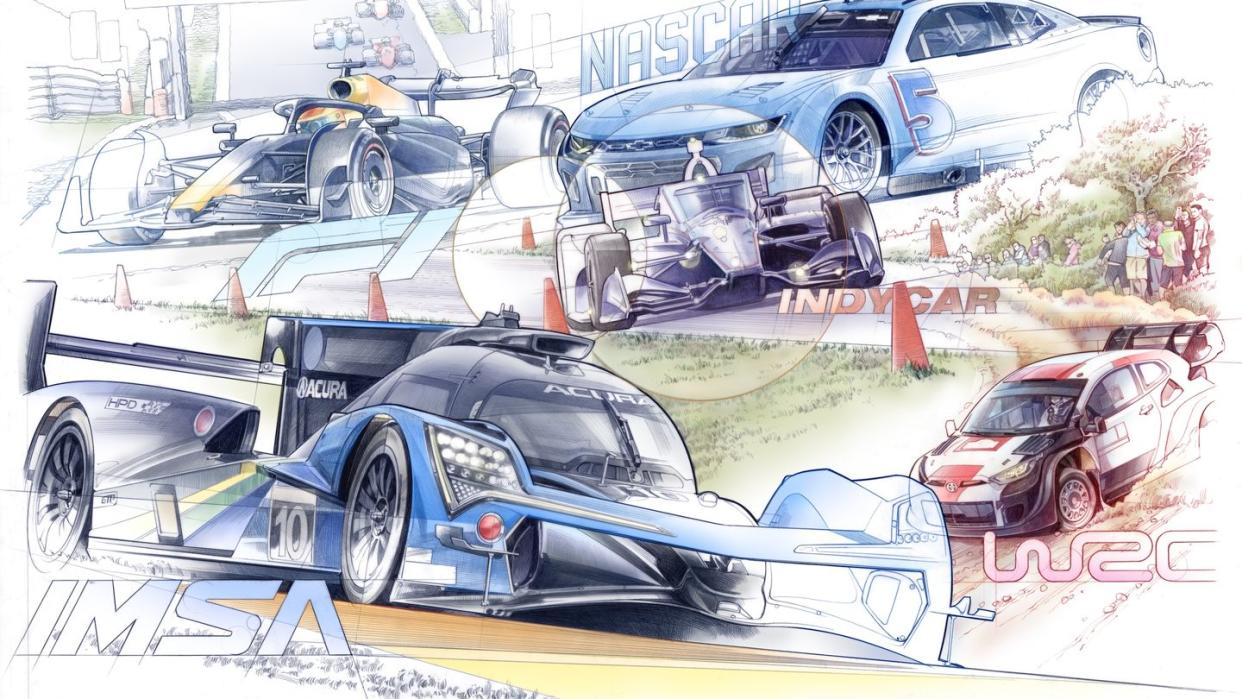

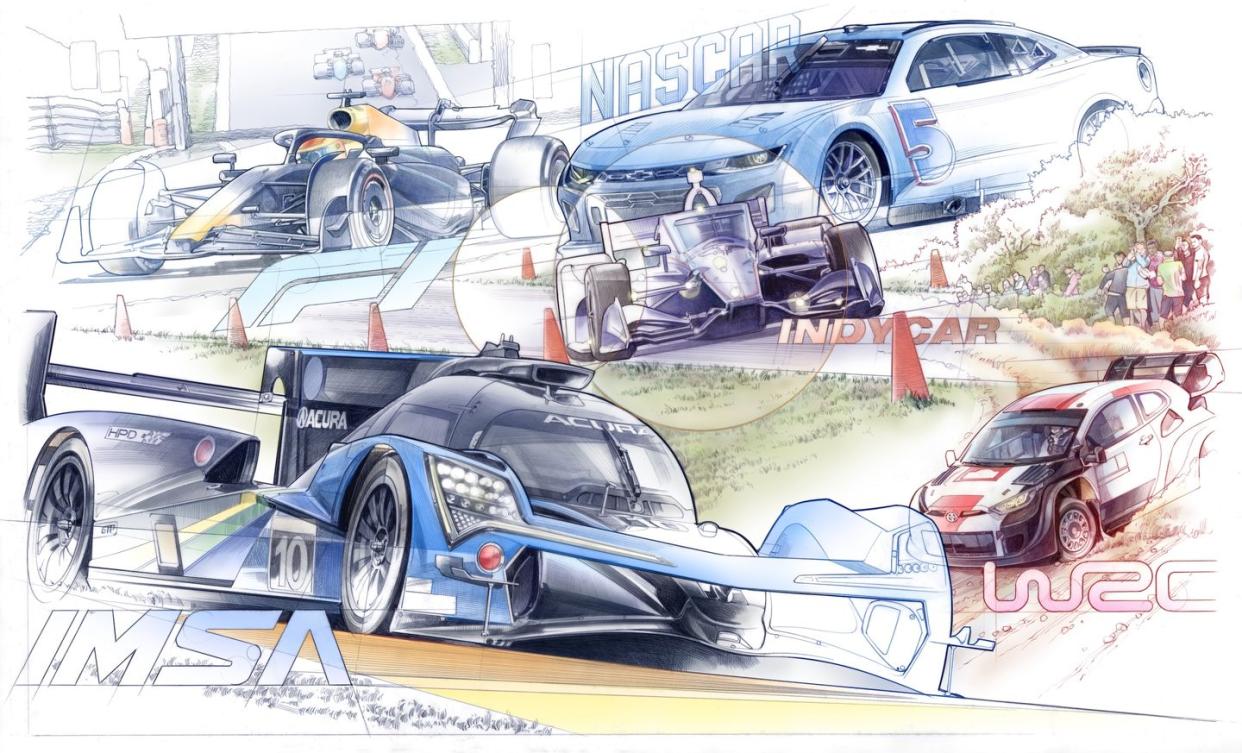

In their efforts to remain relevant, global and domestic racing series have taken wildly different paths with powertrain choices. Lift the bodywork, and in the majority of the cases, there’s still some form of internal-combustion engine (ICE) at play as the base. It’s in the embrace or rejection of electrification where contemporary identity is found.

At the Jurassic end of the engine evolutionary chart, NASCAR and the NHRA serve as pro racing’s last great holdouts, barnstorming ovals and drag strips with primal, mountain-size V-8s. Toyota competes in both series but also in other racing championships where more cutting-edge technology is the standard. It’s using this transitional period in the sport to appeal to all audiences.

“There are social pressures and market pressures on every form of motorsport to reduce carbon in some form or fashion,” says Toyota Racing Development president David Wilson. “And every form of sport is actively looking at that challenge and trying to find the right path for them. Inherently, I think one of the biggest things that we need to continue to solve for is the fan.

"We’re in this time of change, and change is often a scary thing. But something has changed for the better because there’s a lot of interest manifesting itself here.

“Because, yes, we’re all about relevancy. Yes, it’s important to Toyota as an OEM to participate in this solution. But we cannot lose sight of the fact that we are first and foremost in the entertainment industry. And if we don’t fill the grandstands, if we don’t have eyeballs on the television, then we don’t exist.”

America’s most popular racing series was built on relatable and readily available cars and engines. For those who fear the engine is headed toward the graveyard, don’t fret, because there are no plans for stock-car racing’s V-8-powered identity to change anytime soon.

“NASCAR has talked to the fans and asked, ‘What is it that you love about the sport?’” Wilson says. “And one of the basic conclusions is the visceral nature of motorsport. It’s the sound, it’s the smell, it’s the vibration you feel through your bones. And without that, we’re going to lose something. So we don’t feel that, for NASCAR, battery-electric is going to be the right solution. On Sunday afternoon, we’re going to hear noise.”

Further along the evolutionary chart is a dense cluster of hybridization led by Formula 1, IMSA’s Grand Touring Prototypes, the World Endurance Championship’s Hypercars, and the World Rally Championship’s top category. There are some commonalities here, as the quartet combines stout turbocharged or naturally aspirated ICE solutions with battery-based ERS contributing varying punches of electric horsepower on demand. However, there’s no through line to be found with their hybrid-packaging conclusions.

Cylinder counts vary from four to six to eight. Displacements range from 1.6 to 5.5 liters. Electric-motor contributions start as low as 67 hp for the GTP cars and rise to a stonking 268 hp for Toyota’s GR010 Le Mans racer. But Toyota’s system weighs as much as an NFL linebacker. F1’s featherweight hybrid units present a counterargument, generating 160 hp or so from tiny battery packs that could fit into a briefcase.

“The hybrid stuff is here; the all-electric stuff is coming along,” says Salters, the Briton who came to lead Honda’s American racing arm after years of involvement with the Ferrari and Mercedes F1 engine programs. “A lot of development has happened on inverters to make them hideously efficient, almost 99 percent so. And we have electric motors that are also stupidly good. Racing is developing some new and amazing stuff, and all of this is bubbling up through to us and back to our manufacturers.”

F1 opened its door to hybridization in 2009, but it was only partially adopted by the field before falling out of favor. It eventually returned as a compulsory component of the turbo V-6 formula established for 2014, and it remains a centerpiece of the series’s promotional messaging.

F1 has surged in popularity with the general public, thanks in part to Netflix’s Drive to Survive docuseries. Newfound efforts to rein in nine-figure annual budgets through a new cost-cap initiative are trying to level the playing field between teams. The world’s most popular racing series is in the midst of a moonshot as it struggles to accommodate the wave of teams and manufacturers that want to enter its championship. Drive to Survive reveals the human side of F1. Behind the scenes, embracing electrification has helped the sport stay relevant.

IMSA is undergoing the same spike in attendance and attractiveness to global automakers. After switching its leading class from pure ICE to a new hybrid formula that debuted in January, the category doubled in size as the GTP class launched with major factory programs from Acura, BMW, Cadillac, and Porsche. Lamborghini is joining in 2024, and Aston Martin is sending Valkyrie GTPs in 2025, which brings the tally to six.

Brands including Toyota, Ferrari, Glickenhaus, and Alpine have cast their lot with IMSA’s counterparts at the FIA World Endurance Championship. The auto industry’s response to cost-conscious hybridization in motor racing, across open-wheel and sports-car competition, has been anything but tepid—and fans are delighted.

“Look no further than Formula 1, where, for 2026, six manufacturers have signed on the dotted line, including Honda, and there may be one more. When’s the last time that happened? And then look at IMSA and WEC,” says Salters, whose HPD firm is also responsible for Acura’s ARX-06 hybrid GTP machine. “It’s like nine big OEMs, and then two or three boutique manufacturers. When’s the last time that happened? That’s a lot of interest, isn’t it? We’re in this time of change, and change is often a scary thing. But something has changed for the better because there’s a lot of interest manifesting itself here.”

For General Motors, the mating of its 5.5-liter V-8 to Bosch’s spec ERS unit has produced new thrills. Separate from the hybrid’s ability to extend stints in the race, the performative act of launching Cadillac’s V-Series.R GTP model in silence and igniting the engine a few seconds later—like an artillery shell being fired—is resonating with Cadillac road-car customers who otherwise might have adverse reactions to hybrids.

“What’s really exciting for us at Cadillac is this combination of our Cadillac V-8 engine, which has very distinct tonality, combined with the hybrid system,” says Jim Campbell, GM’s VP of performance and motorsports. “And what we’re hearing a lot from fans about it is, during the pit cycle, when we leave the pits, we’re going on electric—instantaneous torque and fuel savings—while we’re accelerating out of the pits. And then at a certain point, we fire the V-8 engine. And that combination is capturing people’s attention. They’re asking about it. They’re interested in it.”

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW Hearst Owned

At the leading edge of racing’s evolutionary chart, we have the zero-emission, open-wheel Formula E series and Extreme E, its off-road sibling. Both rely solely on battery-fed electric motors for propulsion.

The ICE-free counterparts also live in a niche segment of the sport where four-wheeled virtue signaling is the norm. Despite widespread predictions that it wouldn’t survive, and its limited appeal to hardcore racing fans, Formula E has defied the odds. It’s preparing to open its 10th season with seven marquee brands in tow.

As we move toward the end of the decade, racing series ignore electrification at their own peril. NASCAR is the outlier, still filled with jousting dinosaurs that rage and bellow. But NASCAR also understands that spectacle is key to racing—what draws fans to street and road courses, ovals, rallies, and 1000-foot dashes. For racing to survive, rapturous sounds and violent speeds cannot be fully surrendered.

“One thing that does worry me is that not everything is sweetness and light,” Salters says. “This stuff has got to be entertaining. It is entertainment. We’ve got to develop this technology, but we’ve got to use it to put on a good show. This is the best technology in the world we’re developing, but there are still elephants in the room.

“If no one knows what that technology is, or the racing is boring, that isn’t going to be so good. That’s the lovely thing about IndyCar. The racing is stunning. We all have to make sure that becoming a hybrid series does not damage that. We must, actually, find a way to make it better.”

You Might Also Like