‘Abused our trust’: Inside the fraud that keeps hurting small towns in Missouri, Kansas

Over 16 years, Tracey Carman made herself a fixture of small town government in the eastern Missouri city of Center, population 528. As city clerk, she kept the books and took minutes at meetings. Her husband was the police chief.

Carman volunteered at elementary schools and was active in her church. She often watched her son play at the baseball field. The City Council trusted her.

A sprawling, yearslong fraud lurked beneath the surface.

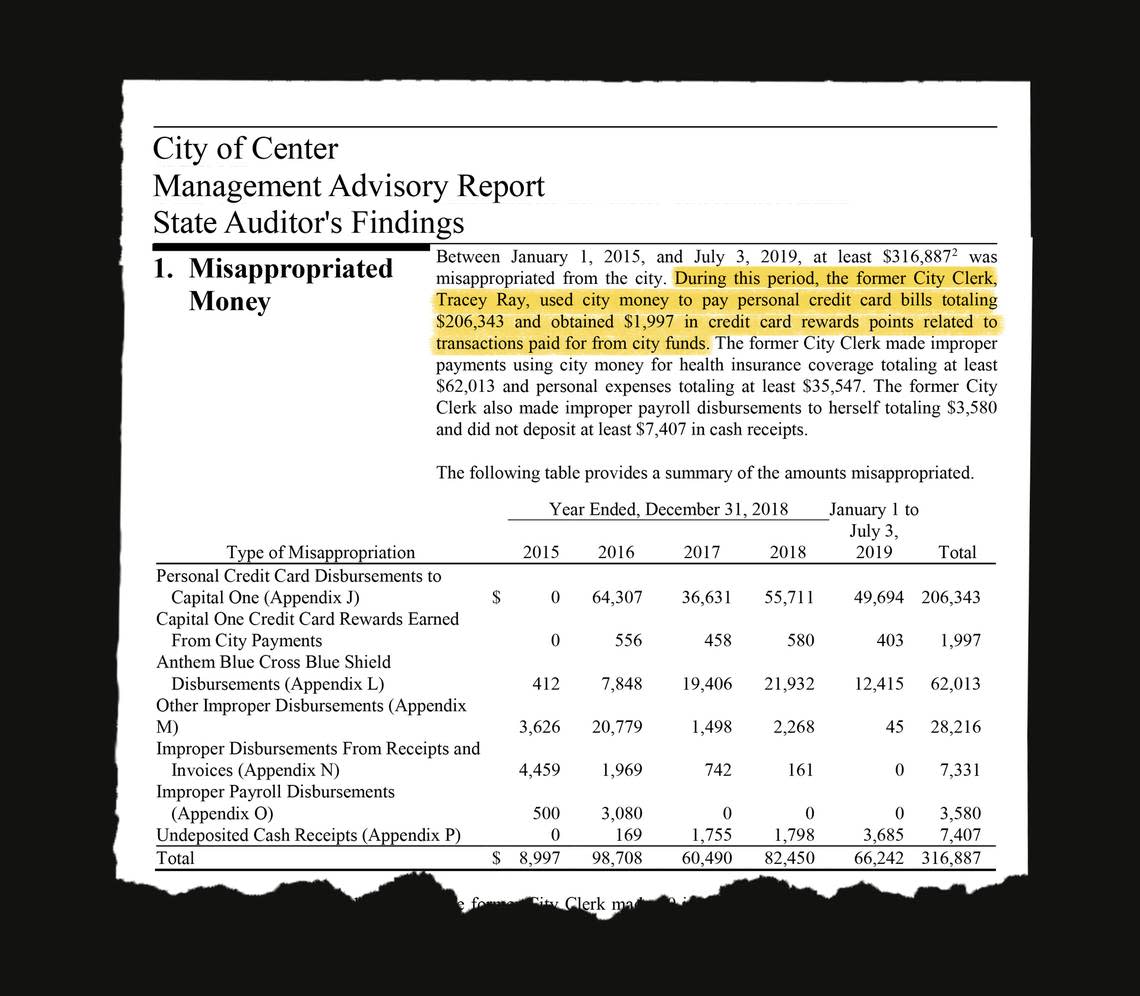

From 2015 to 2019, Carman stole at least $316,887 from Center. She stayed at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, the Harbor Shores on Lake Geneva in Wisconsin, and an Illinois bed and breakfast — all on the city’s dime. Over four years, she spent $2,645 at a hair salon and $9,621 on restaurants. Amazon and Walmart purchases alone totaled nearly $58,000.

Deception kept the money flowing. Carman, then called Tracey Ray, falsified financial reports and lists of bills prepared for City Council meetings.

But she also benefited from the extraordinary level of autonomy city leaders gave her. The mayor and council didn’t probe deeply into city finances or insist on simple methods of oversight.

The scheme collapsed quickly and violently. After learning in late June of 2019 that Center had failed to file required financial reports with the state, the mayor confronted Carman and she promised to address the situation when she returned from vacation on July 1.

Carman didn’t show up for work that day. On July 2, the Ralls County sheriff and a deputy attempted to arrest the clerk, who had a gun. They used a taser on her, and the sheriff’s office describes what happened next as a “shootout” that left both the sheriff and deputy injured.

Carman’s federal public defender said she fired a round into the ground and that the officers shot her multiple times, but she survived.

“Everyone knows everyone, everyone knows everyone’s children, parents, grandparents – it’s a very small farming community, you know. It devastated the town for a while,” said Cristy Browning, a Center alderwoman.

The hard part, Browning said, “was realizing that somebody you respect so much would do what she did.”

While Carman’s case stands out for its shocking details, Center is far from alone in suffering the consequences of financial fraud and mismanagement. A monthslong investigation by The Star shows how small towns and local governments repeatedly fall victim to fraud and how officials misuse public funds in incidents that tear apart communities and deprive them of precious resources.

The Star interviewed dozens of current and former local leaders, state officials, fraud risk experts and small town residents, in addition to reviewing hundreds of pages of court documents and several years of Missouri state audit reports. The investigation found that absent strong safeguards, localities are often a petri dish for fraud and other wrongdoing.

Missouri doesn’t impose extensive financial controls on small municipalities. While Kansas generally requires municipalities to follow basic accounting principles, neither state requires financial audits of small municipalities. Local government associations promote best practices and training, but too often officials stick to how they’ve always done things.

This story is the first in “Broken Government,” a new project from The Star to expose the ways in which government at all levels across Missouri and Kansas fails to work for residents and taxpayers – and hold officials and politicians accountable. Stories will appear semi-regularly in the coming weeks and months and examine everything from Sunshine Law violations in local governments to the problematic use of no-bid contracts and failures in statewide water policy.

Small towns can be especially susceptible to abuses of power, whether that involves financial crimes or the improper use of government authority — like the raid of a local newspaper in Marion, Kansas, by police this month that media law experts have called illegal and unconstitutional.

Investigating financial fraud and mismanagement in small local governments, The Star found that local leaders, either out of necessity or convenience, sometimes place broad financial authority in the hands of a single person and then fail to properly keep tabs on their actions. Basic budgeting and accounting rules are not always followed. Conflicts of interest strain public trust. Violations of open meetings rules keep residents in the dark.

Many municipalities are well run, but examples of the same weaknesses in financial oversight and security emerge over and over again, fostering the conditions for questionable expenses, improper payments and outright theft. It’s a pattern that plays out year after year in community after community.

“There’s no question that in many small communities there’s an overriding sense of well, this is the way we’ve always done it,” said former U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill, a Missouri Democrat who was state auditor from 1999 to 2007.

“And many times that doesn’t include basic controls you need on financial matters.”

In a small Missouri Bootheel town, the acting mayor didn’t deposit at least $66,000 in city receipts, hired her daughter as city clerk and between 2017 and 2019 ran the city without a board of aldermen. A northwest Missouri ambulance district director misappropriated tens of thousands of dollars, auditors say. A northeast Kansas clerk stole thousands in recent years from a town where her father was the mayor.

A small city northeast of Kansas City paid bonuses to employees in violation of the Missouri Constitution. A southwest Missouri city improperly spent $120,000 from a restricted trust fund and paid $17,000 to a business owned by a former mayor. A former local prosecutor in Kansas stole electronics and other equipment valued at $75,000.

More than $1,400 was stolen from the vault of a small town near Branson by someone with a master key. A former clerk in a northeast Missouri town falsified a customer ledger. A former clerk in a mid-Missouri city misappropriated at least $18,900 over half a dozen years, an audit found.

The examples go on.

“I think a lot of smaller governments are so focused on just keeping their operations going, making sure the constituents that they oversee have the services they need, are getting the programs they need, and aren’t really paying attention to this risk,” said Andi McNeal, vice president of education at the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

“That’s a real problem we hear about regularly.”

A 2022 report by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners found government accounts for 18% of occupational fraud cases, with local government making up 25% of those cases. The median loss to local governments in fraud cases was $125,000.

The same qualities that attract residents to small communities – a sense of trust that can come from knowing everyone in town – sometimes curdle into hushing up questions about concerning practices. Those who do speak up can face retaliation and risk getting pulled into feuds pitting residents against each other.

Criminal charge

To be sure, fraud doesn’t just occur in small towns. Last year a former Johnson County District Court accounting supervisor admitted in court she embezzled more than $1 million and created false documents to cover up the crime, for instance. Still, bigger governments and agencies often have more stringent financial security procedures in place.

Missouri enjoys a major check on fraud – a state auditor who often plays a pivotal role in exposing misconduct by issuing public reports. However, while the auditor has a relatively free hand to examine state agencies, Missouri law restricts the ability of the auditor to initiate audits of municipalities.

“We do have the ability to investigate fraud allegations, but our authority stops at an investigation. We can’t go in and do a full-scale audit,” said Missouri State Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick, a Republican.

Currently, municipalities must either invite in the auditor or enough residents must sign a petition. In places where fewer than 1,000 votes were cast in the last election for governor, signatures from 25% of registered voters are required.

Missouri lawmakers this spring weighed legislation that would make it easier for the state auditor to initiate audits of municipalities, and other local units of government. SB 222 would allow the auditor to start an audit after finding a credible report of improper governmental activity, but the proposal didn’t pass before the legislative session ended in May.

Kansas has no state auditor. In turn, episodes of fraud and misconduct in small local governments don’t always surface publicly unless criminal charges are filed – and problems short of criminality may be kept quiet. And in an era of shrinking local news coverage, discussion of problems during city council and governing board meetings may not always draw wider notice.

In Center, Carman blew through what few controls were in place. While the City Council did approve bills based on falsified information, a state audit found the city only required a single signature on checks.

Carman was also the only official making deposits, even though the city hired a part-time clerk in 2018.

“The City of Center is a small community and we are not able to employ a large number of persons, therefore the council and mayor are placed in a position to have to trust the city clerk to do her job professionally and honestly,” Browning and other council members would later write in a letter to a federal judge.

“Mrs. Ray certainly violated that trust, and without regard to the impact it would have on the citizens of the City of Center, abused our trust in a most egregious way.”

But the council could have perhaps uncovered the fraud earlier with more diligence, a state audit report suggested. The mayor and council members didn’t compare bank balances or transactions to a corresponding bank statement or invoice to ensure information was accurate, auditors said.

If board members had performed thorough reviews and required additional oversight, auditors said, they likely would have noted at least some improper payments and inaccurate reports.

Suspicions of misconduct were growing before Carman was caught. Browning, who was in office in 2019, said she ran for office on a platform of examining the city’s finances. Funds in the city’s sewer fund weren’t matching expected balances given the number of customers paying into it, she said.

Auditors would later find Carman had made improper payments of more than $12,000 from the fund and that at least $7,400 in receipts wasn’t deposited into it.

Weak procedure ‘sets you up for failure’

Small local governments routinely fail to adhere to a bedrock principle of financial control and accountability — segregation of duties.

It’s simply the idea that no single person handles all aspects of a financial transaction. More eyes on the books reduces the chances of impropriety.

“You don’t want someone who can basically take in the money … and then account for that money in the books and reconcile in the bank accounts,” said Ron Steinkamp, a St. Louis-based fraud prevention and detection expert. “That just sets you up for failure right there.”

Of the nearly 60 audit reports on municipalities posted by the Missouri State Auditor’s Office over the past five years, more than half found shortfalls with segregation of duties.

“If one person has full control over an entire process … you have the opportunity to not record receipts, so if it’s not recorded and it doesn’t get in the bank no one will ever know about it,” said Kelly Davis, the audit director for local government audits in the Missouri State Auditor’s Office.

Mary Ann Hess, president of the International Institute of Municipal Clerks and the clerk of Laurel, Mississippi, said in her city both she and the mayor sign checks, which the council approves. It’s a simple protective measure Center didn’t follow.

“Then of course everything is audited by outside auditors,” Hess said.

Most larger municipalities undergo regular audits, but many small towns in Missouri don’t. A regular financial audit can help catch misconduct more quickly or deter officials from wrongdoing in the first place.

Financial audits, often performed by certified public accountants, are not the same as the investigations conducted by the Missouri State Auditor’s Office. State auditors are empowered to examine the entirety of a city or agency’s operations, while CPAs focus on financial matters.

In Kansas, local units of government with gross receipts or bonds of more than $500,000 must undergo an annual financial audit by law, and those with between $275,000 and $500,000 in receipts or bonds must be examined annually by an accountant using “agreed-upon procedures,” state law says. In Missouri, the state constitution requires municipalities to prepare annual budgets, annual financial reports “and be audited.”

Richard Sheets, director of the Missouri Municipal League, interprets the constitution to require annual audits but he acknowledged many small towns don’t have one every year.

“We encourage them to have an annual audit,” Sheets said. “It may be costly, but it’s cheaper in the long run.”

Missouri law requires cities that operate sewer systems to have annual audits performed on sewer-related accounts and funds. Center didn’t obtain those required audits, however.

“St. Joe is audited all the time on some of those things. We have an independent auditor come in to run that audit,” state Rep. Bill Falkner, a St. Joseph Republican, said.

“Now in some of the smaller municipalities they don’t have the financial funds available to do it on a yearly basis,” he said. “But I think it could be done every three years or something along that line.”

Former state Rep. Don Rone, a Portageville Republican, said all cities should be required to have an annual financial audit. He called it a “simple fix.”

“They’re gonna come back to you and say, ‘Oh, my God, that’s gonna cost so much money to have an audit.’ But … I would say that would be the easiest way for the state to fix it,” Rone said.

Poor oversight allows problems to fester

Davis, the local government audit director in Missouri, acknowledges ideal practices and procedures aren’t always possible. Some municipalities are so small and have so few employees that it’s not practical — or even possible — to divide financial duties among workers.

But in those cases, she and other experts say it’s incumbent upon local leaders to pay extra attention to finances. Sheets said that’s when the mayor and board of aldermen “really has to step up and have that oversight.”

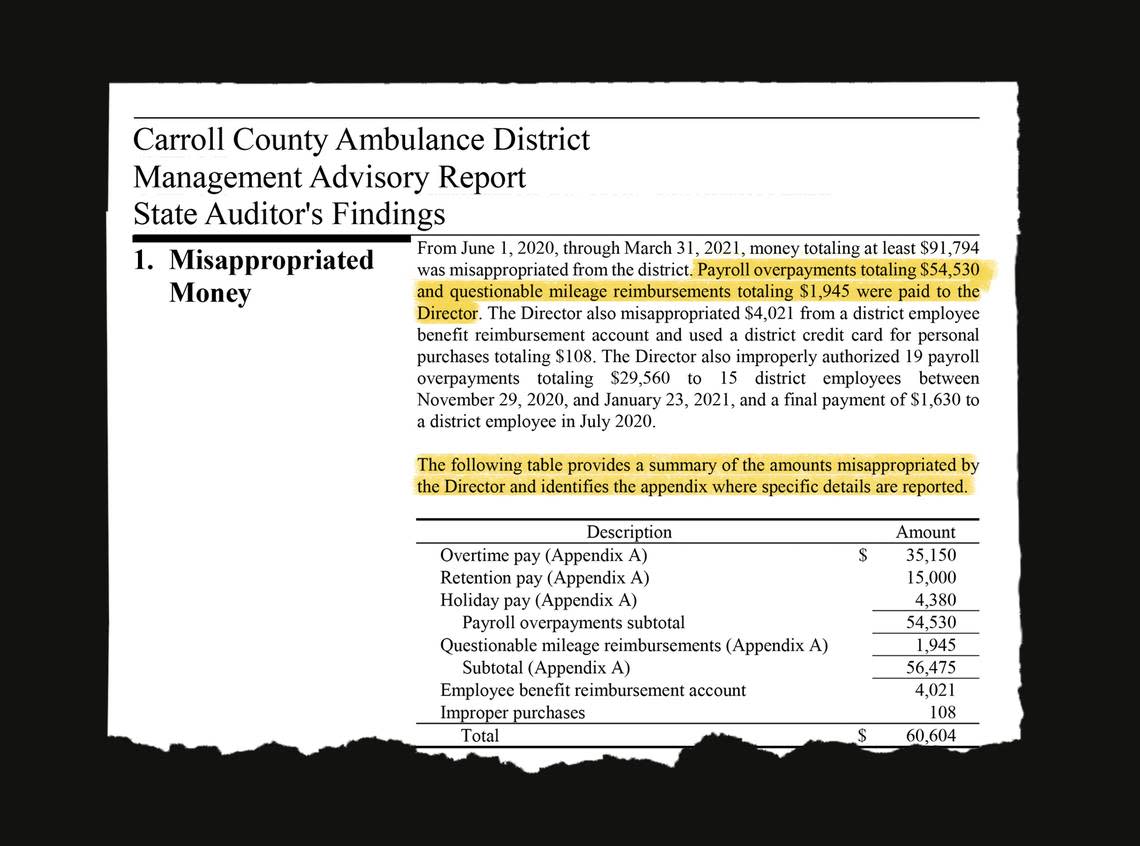

The Carroll County, Missouri, Ambulance District demonstrates the dangers of not following that advice.

The district’s three ambulances and roughly 20 employees service the county, a largely rural area with a population of about 8,400 northeast of Kansas City. Amid the pandemic in 2020, the district’s relationship with county leaders and the local hospital collapsed.

The district refused to provide permission to the Carroll County Memorial Hospital to use the hospital’s own ambulance – permission required by state law. Hospital officials said they were denied the use of the extra ambulance even as the district itself sometimes refused to transfer hospital patients to other facilities.

The district, then led by Administrator Mario DeFelice, applied for $212,000 in federal COVID relief. The county commission wanted the district to receive only $60,000, however, and with the condition that it would pay back any improperly used funding and would allow the hospital to use its ambulance.

“We chose not to fund the ambulance district because of our concerns with the way the district was being run,” Carroll County Presiding Commissioner Stan Falke said in a recent interview.

The strings attached angered DeFelice, who told commissioners in an email that they “should be ashamed of yourself” for withholding the funding.

“We were not friends with the ambulance district director after that. He sent some emails that I won’t even repeat to you what was in them,” Falke said.

As frustrations mounted, DeFelice was terminated in March 2021 and the ambulance district board contacted the Missouri State Auditor’s Office that same month with concerns about the district’s finances.

Behind the scenes, DeFelice had misappropriated tens of thousands of dollars, according to a state audit report released last fall. Between June 2020 and March 2021, the director was overpaid $54,530, misappropriated more than $4,000 from a district employee reimbursement account and improperly authorized $29,560 in overpayments to 15 district employees.

When auditors investigated later, they found that the ambulance district board had never had a written employment contract with DeFelice, and board members said he had refused to sign one. The board didn’t review time records or approve payroll transactions or reports. If they had, board members may have caught some overpayments.

Those kinds of problems aren’t unique. Fitzpatrick called the manipulation of payroll records a “big issue.”

“When you have someone who is being paid hourly, it’s very easy for timesheets to be manipulated and for people to be paid more than they’re supposed to be paid – especially when you have one or two people involved in the payroll process,” Fitzpatrick said.

DeFelice hasn’t been criminally charged. He has previously listed an Olathe address in court documents. When The Star called a phone number for DeFelice, a person who answered hung up after a reporter identified himself and said he wanted to speak with DeFelice about the audit of the ambulance district.

“Report whatever you want to and I will deal with it at a later time,” DeFelice told auditors.

Carroll County Ambulance District board president Karen Miller declined to comment.

Over the past two years, the district’s practices have been overhauled. The board hired Joe Campbell, a paramedic from nearby Sweet Springs, as the new director and now uses multiple levels of oversight for payroll.

Once a month, a board liaison meets with employees without Campbell present so any concerns can be raised with the board directly.

“Any government agency, tax-based agency, government transparency is key,” Campbell said. “That is where it’s at. If you are open and willing to give the information that the citizens or public or news media wants, then that helps tremendously with their trust that you’re operating appropriately.”

Conflicts of interest cause trouble

Conflicts of interest can severely undercut public trust, however.

In Belvue, a city of about 180 in Pottawatomie County, Kansas, Kimberly Fitzgerald worked as the clerk while her father, Leroy Brunkow, was the mayor.

A new mayor, Noah Stutzman, was elected in 2019. A year later, Stutzman and another councilman met with a Pottawatomie County sheriff’s detective, where they laid out a suspected fraud and theft from the city by Fitzgerald spanning a decade, according to an affidavit of probable cause released to The Star by the state district court.

After the Nov. 5, 2020, meeting, Detective Eric Green opened an investigation and found overpayments to Fitzgerald, as well as payments of more than $61,000 to a trucking company owned by Fitzgerald and her husband, despite the city having no known contracts with the company. The total known loss to Belvue was $191,125.18, Green wrote in the affidavit.

City checks bore the signatures of both Fitzgerald and Brunkow. Multiple signatures on checks is supposed to help cut the risk of fraud, but in an interview with Green, Fitzgerald said her father did not always sign the checks.

“I am his daughter so he trusted,” Fitzgerald said, according to Green’s affidavit.

Kansas law requires at least two signatures on checks, according to Nathan Eberline, director of the League of Kansas Municipalities, who added that some municipalities require three signatures.

Fitzgerald pleaded guilty to a state theft charge later that year. She didn’t respond to a request for comment. Court records do not show criminal charges filed against Brunkow or Fitzgerald’s husband.

Stutzman said in an interview that the theft was a financial blow to the city, delaying some maintenance work around town. Stutzman said officials tightened up their practices and the city switched to a local bank, which he said is more likely to know depositors and customers.

“It’s never good practice to have the mayor’s daughter or anybody who’s writing the check keeping the books. That just doesn’t work,” Stutzman said.

The acting mayor of Holland, a town of about 200 in far southeast Missouri, hired and paid her daughter $800 to serve as city clerk for three months in 2021 in violation of the Missouri Constitution, according to auditors.

Jessica Roach was acting mayor from at least December 2017 through April 2021 and had previously been city clerk. State auditors said it was unclear when Roach became the acting mayor – there was no minutes or other record of her taking the position, but as of December 2017 she was the only signature on city checks.

Roach didn’t appoint aldermen to fill vacant board positions or call a special election to fill the board, allowing her to run the city unilaterally as an unelected official for more than a year. During that time, auditors say, Roach didn’t deposit city receipts totaling at least $66,480. A review of Roach’s personal bank accounts noted large cash deposits totaling more than $66,000, according to an audit report.

“Because it is anticipated that criminal charges will be filed, no comment will be made at this time,” Terry McVey, an attorney representing Roach, told The Star.

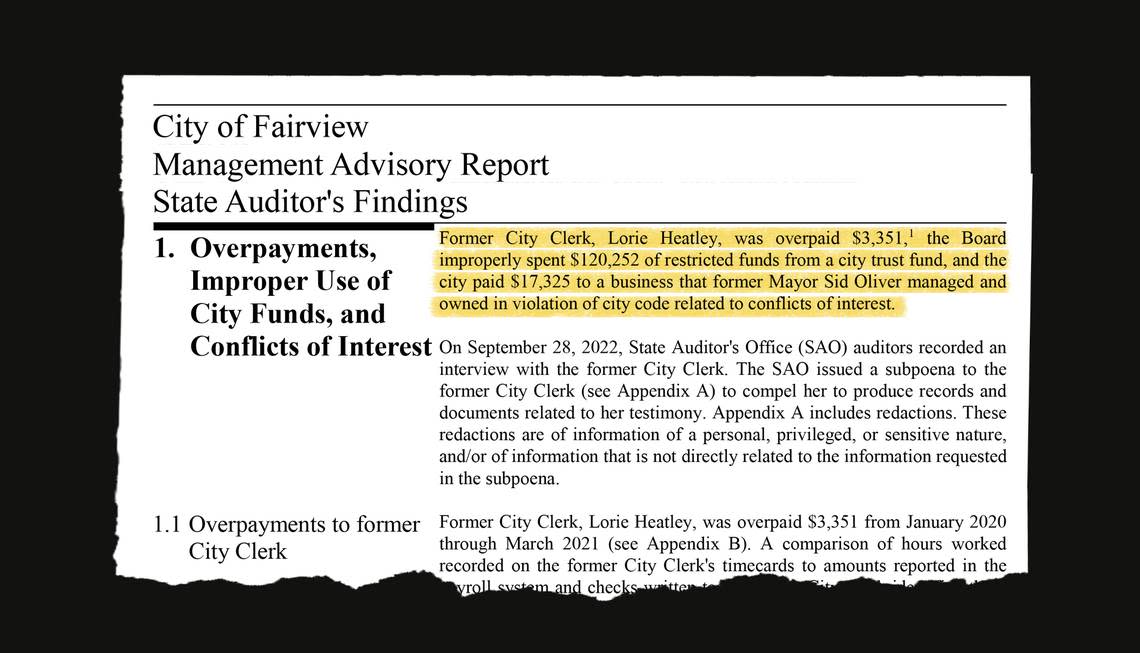

In Fairview, Missouri, an audit revealed that officials violated the city’s own conflict of interest code when they paid a total of $17,325 in 2019 and 2020 to a business owned by Sid Oliver, who at the time was the mayor of the southwest Missouri town of about 400.

Oliver’s business, R-Shop, performed general maintenance for the city. But Oliver also signed 17 of the 51 checks issued to R-Shop while he was the mayor. Bids weren’t solicited and the city didn’t have a written contract with R-Shop. Oliver, a longtime political leader in Fairview, had previously pleaded guilty in 2009 to a misdemeanor ethics violation.

The Star called a phone number for Oliver listed in court documents, but the line was no longer operative.

Financial controls by city officials at the time were poor. The clerk and treasurer signed their own payroll checks, for instance, and the clerk also occasionally signed payroll checks of the meter reader, who was her grandson. The city also didn’t monitor credit card limits and had 24 checking accounts, which auditors called excessive.

The city also improperly spent $120,252 from the trust fund of John Q. Hammons, the billionaire Springfield real estate developer who died in 2013, auditors found.

Hammons was born in Fairview and the trust provided $500,000 to establish an endowment to run a local community center. But city leaders used a portion of the money to purchase buildings around town in violation of an agreement with the trust.

Barbara Stapleton, a former Fairview alderwoman who submitted a petition that forced state auditors to investigate, said that when she and her husband, Raymond, moved to town in 2018 they were immediately approached by residents urging them to run for office.

“These people are terrified, that’s why they came to us. We were new blood,” Stapleton, 74, said.

Raymond and Barbara Stapleton both spent time serving on the board of aldermen – and both fought efforts by other board members to remove them.

A court overturned an impeachment of Raymond and at an August 2022 meeting, the mayor and two aldermen attempted to remove Barbara and appoint three others, including Oliver. A Newton County judge later reversed the board takeover.

Barbara Stapleton said the couple has endured a fire bomb in their yard, as well as a torn-up fence and having the gates to their pasture removed.

Incident reports from the Newton County Sheriff’s Office indicate several calls by the Stapletons to law enforcement in 2022 and early 2023. During one call in September 2022 about a damaged fence, Barbara Stapleton told a sheriff’s sergeant she “has had numerous problems with citizens,” according to the officer’s written narrative.

“They couldn’t intimidate us. Our kids don’t live here,” Stapleton told The Star. “They had nothing on us so there was no way they could intimidate us because we knew that what we did was right.”

Center moves on

After Center’s city clerk was shot in 2019 by the county sheriff, the council voted to fire her and request a state audit. Her husband resigned from the police force and they soon divorced.

Federal prosecutors charged the former clerk, Tracey Carman, with wire fraud and theft from a federal program (her ex-husband wasn’t criminally charged). State prosecutors also charged her in the shooting. She pleaded guilty in both cases, and is serving a 10-year sentence at the Chillicothe Correctional Center.

The Star wrote to Carman, who replied in mid-July that she was considering participating in this story. A reporter sent written questions, but Carman didn’t respond.

“Tracey Carman describes this period as a time when she did not feel like herself, however, she knew what she was doing. Taking the money in a way became easy for her,” Kevin Curran, her federal public defender, wrote in a sentencing memo.

“She still has trouble understanding and explaining to herself why, in her forties, she took and followed such a destructive path.”

Center hasn’t implemented every recommendation made by auditors, but it now requires either the mayor or an alderman to sign each check in addition to the clerk, according to a 2021 follow-up report from state auditors. Copies of computer-generated check registers are provided to board members at monthly meetings, along with bank statements and fund balances. The city now uses one bank account for all funds and the clerk performs monthly reconciliations of the account.

“It’s a whole lot different than it was before,” Browning, the Center alderwoman, said. “We’re really on our toes about where taxpayer money goes.”

In July, Center posted the job of city clerk. Pay starts at $20 an hour. The posting lists several requirements – recordkeeping, clerical support to the mayor and aldermen, proficiency in Microsoft Word and Excel.

“Must be a dependable person due to a small work force,” it says.

The Star’s Kacen Bayless and Maia Bond contributed reporting