Will Aaron Sorkin’s First Musical Be a Hit? Why Broadway Director Bartlett Sher Thinks ‘Camelot’ Will Shine

It’s the second day of tech rehearsals for the new adaptation of Lerner and Loewe’s “Camelot,” the 1960 musical based on the Arthurian legend — this time rewritten by Aaron Sorkin — at the Vivian Beaumont in Lincoln Center. All around the theater are long tables shrouded in black cloth where tech people are writing on notepads, flipping switches and speaking quietly into headsets, their eyes never leaving the 4,000-squarefoot stage suspended above the orchestra pit like a massive UFO. Actors in medieval costumes are talking in small groups, choreographers are nervously pacing, a producer is heatedly whispering, and Bartlett Sher, 64, the director, is standing in an aisle near the back, watching silently, like a captain on the prow of his ship.

There are problems getting from one scene to the next: Can Phillipa Soo, playing King Arthur’s new wife, Guenevere, get out of her tight leather pants and ruffled shirt and into her formfitting blue velvet dress in under 37 seconds? How can the knights shed their heavy, floor-length cloaks quickly if they can’t undo the clasps? Should the lights be up when actors bring in the tables, chairs and rug that signify the king’s study, or is that revealing too much sausage-making? And the metal wall that slides down fast from the ceiling into the middle of all this — what if a knight or a lady-in-waiting loses a toe?

More from Variety

Aaron Sorkin Suffered Stroke Last Fall: I Thought 'I Was Never Going to Be Able to Write Again'

'The Ghost of Richard Harris' Docu Solidifies the Mystique of Famed Actor Before He Was Dumbledore

'Pictures From Home' Review: Nathan Lane Leads Well-Acted but Dull Broadway Play

No matter, they’ll try the transition again. The stage manager calls for the scene to start, and everyone takes their places. Merlin, Arthur’s mentor, is dead, and Arthur, devastated, wonders how he’ll be able to create a new order in Camelot — in which everyone has a voice and laws are just — without the man on whom he relies for guidance. On his knees, the young king says goodbye to his teacher, as a curly-headed pianist in a button-down shirt plays a mournful tune and a flock of knights becomes a chorus of baritone sorrow. Then Arthur rises, steps to center stage, and in pure Sorkin fashion, says, “What the hell do I do now?!”

Suddenly the hall is filled with loud, buoyant music. Guenevere rushes off, stage left; the knights exit, stage right; and, after a moment, men in black armor rush in with props. The conductor, standing in the otherwise empty pit, waves her arms, and the choreographers conspicuously snap their fingers to speed things up. All the while, Sher, in the same black sweatshirt and baggy black pants he’ll wear every time I meet up with him, watches, expressionless.

When the scene is done, he comes back to where I’m sitting and says, in a whisper, “That was a disaster.” He pushes a long lock of silver hair behind his ear and smiles, because in Bart Sher’s world, a disaster just might be the most fun thing ever.

After 18 months of COVID-related closures, Broadway has begun to come back to its prepandemic self. A revival of “Sweeney Todd” with Josh Groban, a reimagining of “Parade” with Ben Platt, and the Jessica Chastain-led “A Doll’s House” have all played to packed houses — and Lea Michele has made “Funny Girl” soar again. But if the hard-won rebound is to continue, there needs to be a few more hits for avid theatergoers and tourists.

With “Camelot,” Lincoln Center is resurrecting one of the stage’s best-known shows. And in Sher and Sorkin, they are turning to two of the most successful artists in modern theater, a duo who joined forces in 2018 to turn “To Kill a Mockingbird” into the highest-grossing American play in Broadway history. Not only that, but Sher — regarded as one of the finest American stage directors working today — has been Lincoln Center’s most consistent hit-maker, with revivals of “South Pacific” and “My Fair Lady” running for 1,000 and 509 performances, respectively. But has Sher, who has found ways to dust off creaky musicals and make them relevant to contemporary audiences, met his match in “Camelot”? After all, the initial production’s optimistic look at how ethical leaders harness power to forge better worlds seems hopelessly naive in this divided political environment. Or maybe not — maybe “Camelot” is just what we need.

In 1971, in Sher’s hometown of San Francisco, there was a funeral for a policeman in the neighborhood where he lived, and the door of the church where the service was being held was blown off by the radical group the Weathermen. Sher, the fifth child in a string of seven, was 12 at the time and heard the explosion from his sixth-grade classroom. “It was cool,” he says today, sitting in his small, windowless office at Lincoln Center, where he has been the resident director for the past 14 years. Knowing how that might sound, he quickly adds that no one was killed, or even hurt. But in “the gray space,” as Sher calls it, between him and me — the place where deeper meanings are silently conveyed — I can see why he called a domestic terrorist attack in his childhood neighborhood “cool”: Because San Francisco in 1971, alive with the electric energy of cultural transformation, was blowing open young Bart Sher’s mind.

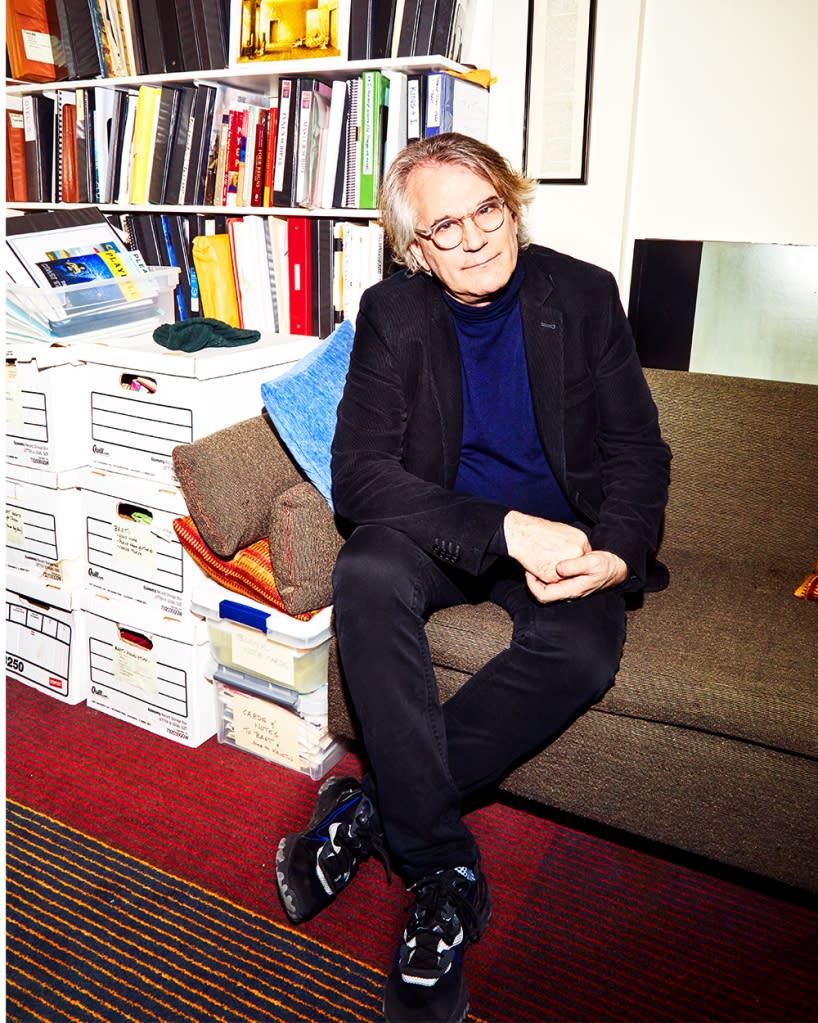

Sher’s office is a mess: Books are stacked every which way on mismatched shelves, and black-and-white photos from stages around the world are stuck on the walls in flimsy black frames. To find something on Sher’s desk requires an archaeological excavation, though when he wants to show you a book — one of the bibles written by Tadeusz Kantor or Giorgio Strehler, the European avant-garde directors who, along with Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka and French director Ariane Mnouchkine, have influenced him most — Sher knows exactly under which pile it’s hiding.

Though he’s clearly brilliant, well-read and confident in his abilities as a director, Sher’s also a mensch. If he has a big ego, it’s pretty well hidden. Sorkin says, “He’s a great director. And if it needed to, his talent would excuse any bad behavior. But he’s also a very nice guy.”

I meet Sher three times over the course of two weeks, for instance, and twice I’m late (let’s blame the New York subways). The second time, I come into the restaurant mortified — how could I have again kept this busy, important man waiting at a table by himself? I can’t stop apologizing. Finally, he moves to the edge of the booth where I can see all of him, and he says, “Do I look angry?” He sits calmly looking at me with no rancor at all on his face. And that’s that. We go on with our interview, in which he is, as usual, a really fun college professor leading the world’s best seminar.

He seems genuinely happy when I tell him that my mother took me to the theater when I was child, and he says, “Well, you don’t have to lie down on railroad tracks to know what it feels like to be hit by a train. …” I look at him quizzically and laugh, and he says, “… in terms of why theater matters,” and smiles. Then he goes on: “It’s an extraordinary exercise for you to explore conflicts, external realities, places you haven’t gone that open up in front you without trauma — without damage to you. It can be the deepest tragedy, the most incredible comedy, the most beautiful musical, the most powerful opera; all of these have this deep resonance inside of us. And so for kids to go see these things — for your mom to be so smart as to bring you to that — is to open up the world to you.”

Sher’s own first big theatrical experience, he says, happened when he was 11: It was a Grateful Dead concert at the Winterland in San Francisco. He’d seen good theater at his Catholic grammar school — he’d even enjoyed putting the colored cellophane over the lights in preparation for a Virgin Mary Christmas play — but there was something about the transcendent experience of the Dead’s endless jams, and the audience members willingness to open their minds and go with it, that never left him.

“Camelot” is one of eight plays that Sher has in production right now. There’s also “Pictures From Home,” starring Nathan Lane, on Broadway; three shows in regional theaters across the United States; and three in England, including “My Fair Lady,” in which Eliza Doolittle leaves Professor Higgins at the end, and the Sorkin-penned “To Kill a Mockingbird,” where Atticus Finch is not the great white savior he is in the 1962 film, but a more divided man — a ’30s liberal who also believes in segregation. Sher directs operas, too, and one of them, Gaetano Donizetti’s “L’Elisir d’Amore,” will be coming back to the Met this season.

He sees himself as an interpretive artist (“like a conductor,” he says), rather than a creative artist (“like a composer”), and he exhaustively researches the history of every play he works on — and the political and cultural context in which it was written — until he feels he understands what the author intended. He’s not imposing his ideas on a play or preaching to his audience. He’s creating a work of art that he feels reflects the playwright’s vision.

The original “Camelot” is entwined with the Kennedy era, because the late president loved the show, and, according to Jackie, used to sing songs from it like “If I Ever I Would Leave You.” A week after Kennedy’s assassination, Jackie told a reporter that the possibility of a Camelot here in America was over, dashed with the president’s murder. To this day, people of that generation sometimes weep when they hear the soundtrack.

Back in his office, though, Sher says, “Great plays come around when you need them.” So it makes sense that, in 2018, with democracy fraying at the edges, André Bishop, Lincoln Center’s artistic director, suggested to Sher that they put on a concert version of “Camelot” for the gala that year. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s mother loved the original show, and so Miranda agreed to play Arthur for that one night. Later, Miranda suggested that Sher revive the play, this time with a better book — one by Sorkin, a master scribe when it comes to the romance of American politics.

Sorkin studied musical theater at Syracuse, but had never written a musical. Yet the project made sense to him. “You know,” he says, “here’s a show that lends itself to the idea that we should reach for the stars, even if we fail. That suits me.” He adds, “I didn’t want it to be a museum piece. I didn’t want it to be an exercise in nostalgia. I wanted it to be about now. I wanted this King Arthur to grow up to be Martin Sheen in ‘The West Wing.’”

Sorkin’s “Camelot” is shorter, and almost all the dialogue is new. The first one was filled with sorcery and magic, and the updated version has none. Arthur, a commoner who becomes king after being the only man able to pull a sword from a stone, dreams of evolving his lawless kingdom into a kind of utopia, by creating a council of men — the Knights of the Round Table — and a system of government where everyone is equal under the law, and those laws are enacted fairly.

In Sorkin’s version, Guenevere enters the picture as the brilliant daughter of the king of France, not just a pretty girl, and so in all ways she’s equal to, if not smarter and more majestic than, Arthur, who, while lovely, is still a boy. So though Arthur and Guenevere are partners in this plan for a wonderful new age in Camelot, it’s not surprising that she falls for a very experienced and confident knight, Lancelot, and he for her, despite the fact that he’s devoted to Arthur and Arthur to him.

Guenevere and Lancelot don’t even kiss in this new version, understanding how disastrous that would be, until one night when Arthur’s illegitimate son, who lusts for the throne, manipulates the situation so that the two are thrown together and make love while Arthur is away. They are caught, tried and sentenced to death.

It’s a tragic story about our longing for what’s good and our tendency toward darkness. And it’s actually heartbreaking, at the end of the play, when you realize that the dream of democracy — and a marriage with so much potential — could fail because of very human frailties all around. “When we see Aaron’s play,” Sher says, “we wonder whether we’ve lost our own Camelot. Where are we as a country? Is there something that’s perhaps broken and falling apart? Can we get that back? That’s the very deepest subtextual level at which I’m trying to answer the question, ‘Why “Camelot”?’ And when we betray our own values and do something because of our own personal desires and impulses versus who we are — that makes for good theater.”

“What if you fail?” I ask Sher over dinner. We’re having meatballs and polenta, which he’s had many times before, but he’s devouring them. “Oh, come on,” he says. “It’s so fun, if you aren’t putting on yourself the pressure of success. I’m there to explore. Of course we want it to succeed, but that’s not the issue — it’s not the issue for my vision to be realized. The issue for me is to lead everybody toward something.”

I don’t quite understand how a man this worldly — so steeped in global experimental theater — ends up directing big American musicals like “Camelot.”

“I think as artists who are Americans,” he says, “we have a responsibility to explore our own history, and to bring everything we know of our craft to the work that speaks to our people. And I think the American canon — and the American experience of who we are on every level — must be reinvestigated. The history of who we are is changing radically, in the same way that it was changing for Rodgers and Hammerstein or Thornton Wilder or Tennessee Williams or August Wilson. We’re trying to evaluate who we were and who we are.” He gingerly takes a bite of salad and adds, “That’s what I like to do, make connections between things.”

Back at the tech rehearsal, three knights are silently moving down the stage in the direction of the seats, their black cloaks dragging on the ground behind them. I say to Sher, who’s standing in the row in front of me, that it looks Shakespearean.

He says, “I’m trying to make this feel like a history play. Because, you know, it’s Arthur. And because Aaron’s language is elevated and powerful. So I’m trying to lift it to a kind of real place.”

“As opposed to what?” I ask, and Sher leans toward me, makes fluttery jazz hands up around his ears, and whispers, “Theater-y.”

Best of Variety

'House of the Dragon': Every Character and What You Need to Know About the 'Game of Thrones' Prequel

25 Groundbreaking Female Directors: From Alice Guy to Chloé Zhao

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.