Meet the 98-year-old Shawnee woman who’s one of the last WWII veterans in Kansas City | Opinion

During the Blitz in her hometown of Norwich, England, young Sally Hatch slept every night in the underground air raid shelter in her family’s garden. “I didn’t particularly like that,” and one night refused to go — until, that is, she was allowed to stay up in her bedroom for a few hours, and got to see that the alternative to joining the others was much more harrowing. Down in the shelter, her mother kept her six children singing, to distract them at least a little from the German bombs falling nearby. “I don’t recall panicking,” Sally told me. “It was part of living by that time.”

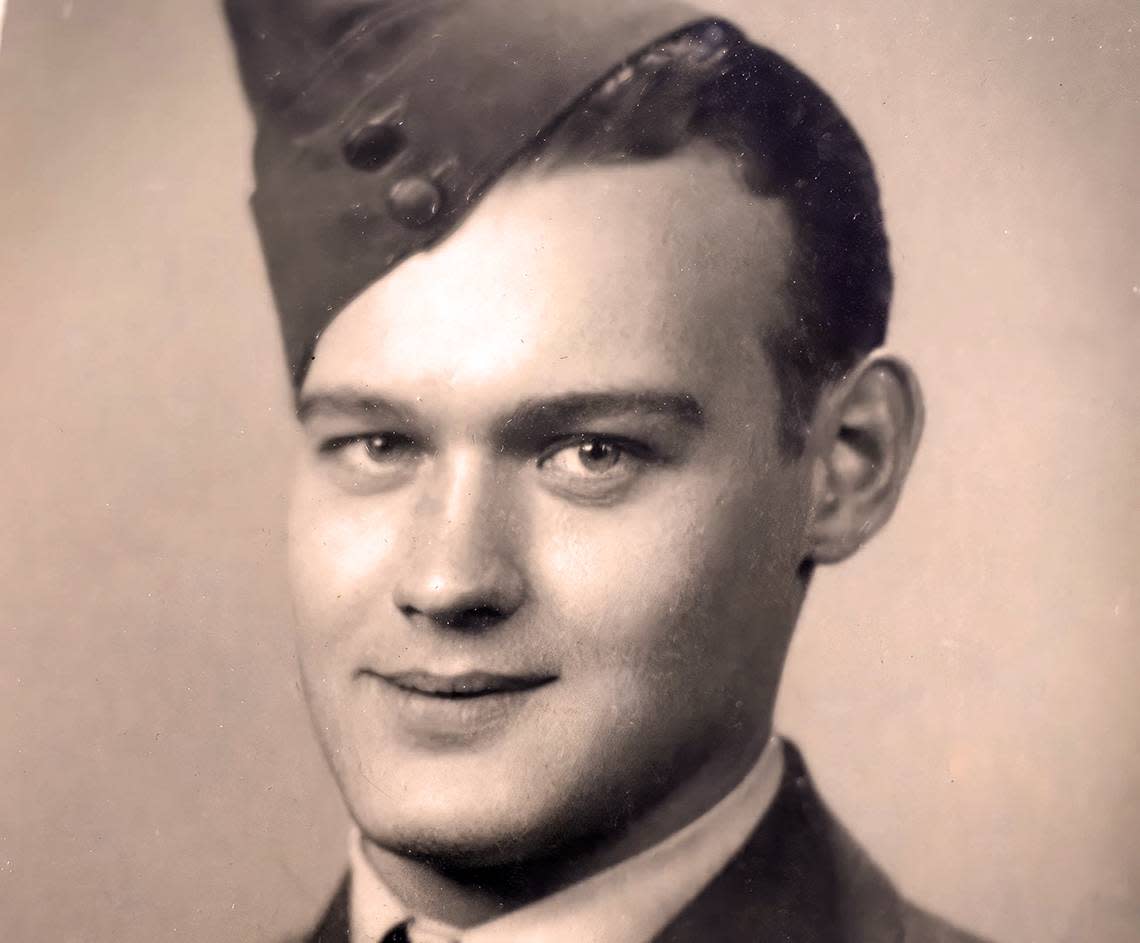

At 16, Sally joined the Royal Signal Corps. “I lied about my age” to get in, she says, because “I had to do something for my king and my country.” At 17, while serving in Scotland, she met her “very romantic” husband, 21-year-old Sedalia, Missouri, native Marion Keithley, who went by his middle name, Cal. He had trained in Canada and was attached to the Royal Air Force because we hadn’t yet entered the war. Like Sally and so many others, he couldn’t wait to serve.

This Monday, 98-year-old Sally Hatch Keithley-McCulley, who lives in Shawnee, flew to France for several of the many observations of the 80th anniversary of VE-Day. She’ll be there, in Laneuville-à-Bayard, for the Wednesday ceremony honoring her fallen RAF airman brother, Ernest Hatch. At just 22, he was shot down there, and his grave in the village churchyard, along with those of six other men who helped save the world from the Nazis, has been lovingly tended for these last eight decades.

Before she left, I had a cup of tea with Sally, who still drives a Mustang, by the way, and I can report that it’s never too late to have a new role model. Did they know then all that was at stake? Not really, she said, though “we were dedicated,” and she “loved, loved, loved” her work in the Signal Corps, taking and passing on messages about where planes would be at a certain time.

Later, she worked on the radio in the underground command post of a heavy artillery battery. “At 16, I felt very important.” As she was coming out of the Old War Office in London one day, she saw a big car with American and British flags on it pull up, “and oh my gosh, it was Eisenhower and Montgomery.”

Were relationships more — to use her word, romantic then, or do we just think that? She’s pretty sure that they really were.

Married 3 days before D-Day

Sally and Cal met at one of the regular Sunday night dances in Edinburgh, where both were stationed, that neither had ever attended before. His commanding officer asked, is there anyone in particular here you’d like to meet, and he said yes, I’d like to be introduced to that redhead standing in the doorway, “and that happened to be me.”

From that night on, they walked and talked, walked and talked, covering many miles and lots of history, which they both loved. Then one day, he brought her where he said Mary, Queen of Scots used to meet her lover, and proposed at the man’s grave, which they both then sat down on. At 17, she wasn’t quite ready for the ring he hoped she’d wear: “I had so many boyfriends” that “I said no, you know?”

Some of the first American airmen stationed in Norwich had been so much less respectful than they ought to have been — “Some of these airmen were a little high, and Churchill asked Roosevelt to remove them,” which he did — that she wasn’t sure how her family would feel about this particular boyfriend.

That wasn’t Cal Keithley, though, and after they, too, fell in love with him, she started wearing the ring. Her brother Ernest was shot down on April 27, 1944 — also the day her mother smoked her first cigarette, pressed on her by the doctor who thought it might “calm her down” in her grief.

It didn’t, of course, but what did help was learning that “the French people were so grateful because they could have landed the plane on the village” and instead, as they crashed, steered it into the field where its debris still remains today, in honor of their sacrifice.

Cal and Sally married a few weeks after Ernest’s death, on June 3, just three days before D-Day, and on their honeymoon at her oldest sister’s house in Norwich, they watched “hundreds and hundreds of planes on their way to Europe. It made a tremendous noise.” One that in a sense we can still hear now, or ought to.

She remembers Winston Churchill as “a wonderful man and lovely speaker who helped us all. He was a soldier, and a writer like yourself.” (Yes, I wish.) “He was a very strong man, and everybody loved him.” Or she did, anyway.

At the war’s end, in 1945, she and Cal sailed to New York on the Mauretania, with Sally crying all the way. In Kansas City, Kansas, they raised a son and a daughter in a house on Lathrop Avenue that Cal built himself. He worked as an electrician for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and she spent 30 years as a switchboard operator for Simmons Bedding Company.

‘Felt so sorry’ for family of man who raped her granddaughter

At 98, of course there have been losses — of Cal, who died of leukemia in 1985, and then of her second husband, Gene McCulley, 14 years later. In 2017, her beloved granddaughter, Shannon Eileen Keithley, who used to stop by and see her on her way home from her job repairing string instruments, was raped by a man who’d broken into the KCK house Sally had given her. She eventually broke free, but then, in her panic to escape, wrecked her car and died in the accident.

The bouquet of flowers that Shannon had sent Sally for her birthday that year, not long before she died, is still on the table in her front room. “I really do miss her, even now,” says her grandmother, who asked that ‘Over the Rainbow’ be sung at Shannon’s funeral.

Yet because this is a woman who has so much to teach us on any number of fronts, she also says that at Shannon’s attacker’s trial, where she had to listen to the 911 tape of her girl crying, “Help me! Help me!” “I felt so sorry for his mother and his brother, and gave them both a hug.”

A 50-year Star subscriber, she reads the paper every day, and because of what she’s seen of war, “when I see pictures of Palestinians, I really feel sad for them.”

‘A very brave couple, my mother and father’

Despite all she’s survived, though, Sally also seems like she might have been the one who invented joie de vivre, and she was so excited about celebrating VE-Day, which “as it turned out, is on my mother’s birthday.”

She has outlived all of her siblings and is one of only five surviving WWII vets around here now, she says. What she most wishes she could convey to younger generations is that in those moments and places when “people just helped each other,” that’s what mattered and what is worth remembering.

Her father, who’d fought in WWI, wanted to enlist in 1939, too, but was told that with such a big family, he was more needed at home. So at night when the sirens sounded, “he’d walk around and make sure everybody had their blinds down. They were a very brave couple, my mother and father, so we had to be, too.”

She still has a pair of shoes designed by her sister Dolly, and made at the factory where both Dolly and her father worked. “I don’t wear them,” she says, laughing, “because I don’t want to wear them out!”

Her advice on living a long and also good life involves eating lots of fruits and vegetables, but also a little chocolate. “And if I get an ache and pain, I don’t rush to the doctor, but take care of it myself.”

Sally, when I say thanks for everything, I mean that literally.

If you want to help defray the cost of her trip to France, which was made possible by Patriot Features, a group that documents the stories of veterans, you can do that here, at patriotfeatures.org/donate