At 80, Yohji Yamamoto is Still Curious

If you want to know the way to gently scandalize Yohji Yamamoto, just mention his birthday. On October 1, two days before his 80th, the suggestion of hosting a small celebration made Yamamoto’s team’s eyeballs enlarge. They looked worriedly at each other. One threw their hands up in a comically panicked gesture. “I want to forget about my birthday,” the designer said, smirking from across a wooden table in the attic of his studio in Paris’s Marais district.

Yohji-san, as his staff calls him with a blend of reverence and love, wears eight decades with a mischievous twinkle in his eyes. Even after seeing it all—he describes everything from being hit by a Japanese gangster as a child to flying an airplane over Boston during our expansive conversation—he remains as up for anything as ever. The urge to create or to provoke hasn’t diminished one bit.

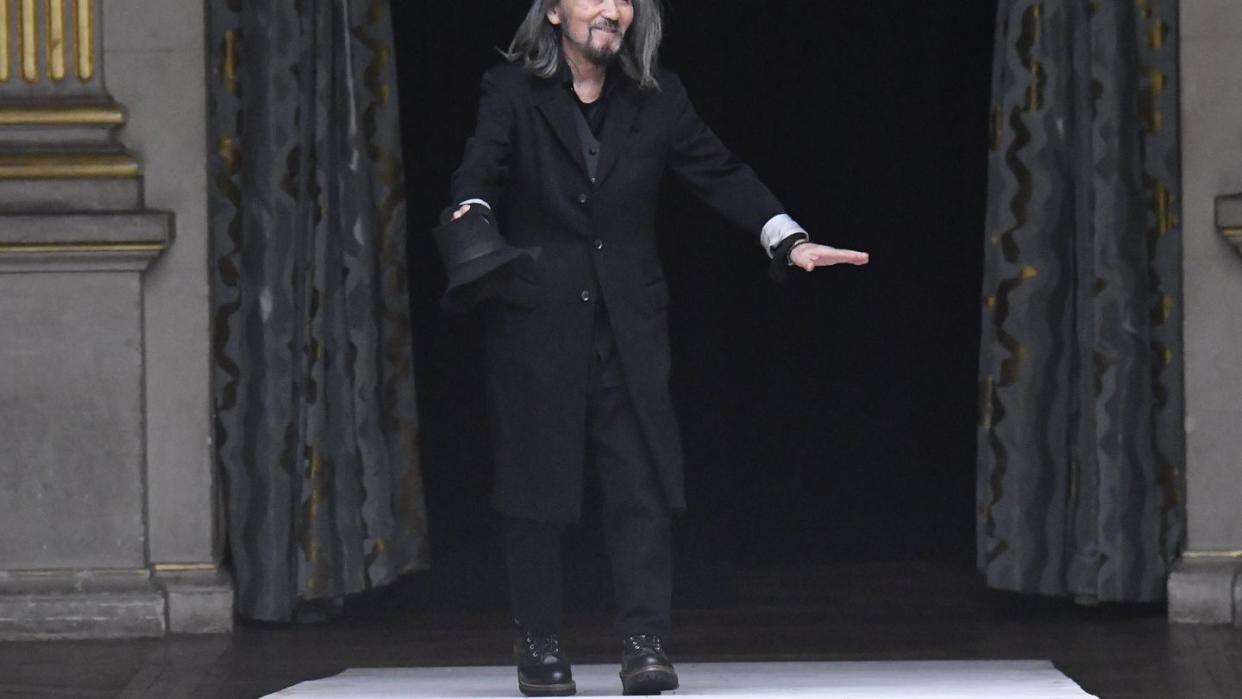

The proof is in his latest womenswear collection, presented in Paris’s Hotel de Ville. Nearly entirely black, with streaks of bleached dots, slashed waists, and metal-wired sculptural shapes, the collection is sensual, punk, and austere—a reflection of Yamamoto’s mood at the moment. “I asked the patternmaker to make something where people can see skin, not breast and not hips,” he says. “I love women, I respect them, so I never show breasts and hips, but maybe back or side or from here,” he continues, gesturing to the upper thigh, a sliver of skin revealed in the black long dresses that closed the show, humble sack shapes with slashed pockets over and high slits up the sides. The very Yohji combination of something somber and hot.

“At the same time I was inspired by young people because times are changing and young people have a totally different culture than I have,” the designer continues. “I’m studying it.”

What does he see when he looks at a younger generation?

“They’re losing the dream of the future. It’s very painful,” he explains, citing a lack of governmental support in his native Japan, “and in the world where there are many kinds of wars and after the coronavirus…It is painful. So I am not simply enjoying creating a collection. I have to think about the world’s condition. Don’t you think about the world's condition?”

“Yes,” I reply. “But I think a lot of younger people look at your clothes and your collections and see them as a source of optimism.”

“Optimism, yes. I see,” he says reluctantly. “I don’t know why young people respect me. Love me. I don’t understand. It’s too much” He smirks slightly again looking away.

“Many young designers look at your clothes, and collect them, or try to replicate them in some capacity. Is that inspiring or annoying to you?” I ask.

“Annoying,” he says quickly. “I have been working and creating fashion collections already for 40 years. When I started, I had so many respectable designers and after 20 years I had so many competitors. But four or five years ago, I lost all the competitors. They disappeared or they stopped. So I feel very alone. This feeling makes me have responsibility [to design]. But at the same time it becomes hard to be sharp to create something. So anyway, my position at my job became heavier than the whole.”

The heaviness is belied by the lightness of Yamamoto’s work, as heavenly as ever, this latest collection is made from airy linen fabrics. Those peaked shoulders in pale ivory that opened the show are made without any padding at all, to un-encumber the wearer, and dotted with white buttons down the back to allow for added movement or sex appeal. Tailoring comes in every kind of vest and blazer combination, unlined inside to expose the genius of the silhouette, and shoes are always flat, like a sneaker or brogue.

It’s easy to understand, when you see the relaxed confidence with which customers wear Yamamoto’s pieces, how he finds inspiration in city folk dress. Driving each day to work in Tokyo, “people pass, and I find kind of unique fashion, unique way of wearing an outfit,” he says. “So mainly when I'm driving a car, the impression comes down to me. The idea or some present comes down—I catch it.”

It’s this appreciation for real life—and real clothes—that’s made Yohji Yamamoto the king of New York style. Think about it: There would be no New York aesthetic without him—all black, sleek but soulful, and irreverently naughty. Once the uniform of Carolyn Bessette Kennedy and downtown gallerists, a Yohji Yamamoto suit is now the grail item for hypebeasts and smart women alike. It’s why the brand has reopened a megastore in Soho, at 52 Wooster St., to house all of its collections from its main line to Y’s and Y-3.

Of America, the designer has only positive things to say, drawing analogies between his status as a self-made man to American culture and recalling trips to the states to visit friends. (Rumor has it Yohji-san may also make an appearance this autumn to celebrate the opening of his store.) But perhaps the most shared quality between us Americans and Yamamoto is that balance of joy and subversion, mischief and success, polish and punk.

“I do, I do like New York,” he says. “About 20 years ago, I was a little bit tired of creating collections. Then I went to New York and saw New York business people had started wearing sneakers to go to the office and I was inspired by sneaker fashion.”

He pauses, and smirks once again. “I know the meaning of sneaking.”

You Might Also Like