80 kindergartners, 5 adults: Could a new teaching model come to Michigan schools?

In February, as winter wore on across the Midwest, a group of Michigan school administrators found themselves in the desert.

Not on vacation — they rarely were afforded the chance to enjoy the Arizona sun at all, and one day during their visit it rained, they said. No, they mostly spent their time in classrooms. The Michigan administrators were on a quest for information, a search to bring an Arizona experiment back to some of the state's classrooms.

And a few think they found it: a model of teaching that involves a team of educators teaching a large group of students — sometimes as many as 100 students to five teachers. The concept recently took shape in Arizona schools, as a part of an idea developed by Arizona State University's Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College.

The idea is that students need more educators, not fewer. The way it's executed depends on the school. Some schools have large classrooms to accommodate as many as 100 students, while some schools have kids sorted into groups that circulate from one classroom attached to another. At Stevenson Elementary in Mesa, Arizona, 83 first and second graders filter into the same room in the mornings for a "family meeting," before breaking out into groups and visiting their different teachers throughout the day.

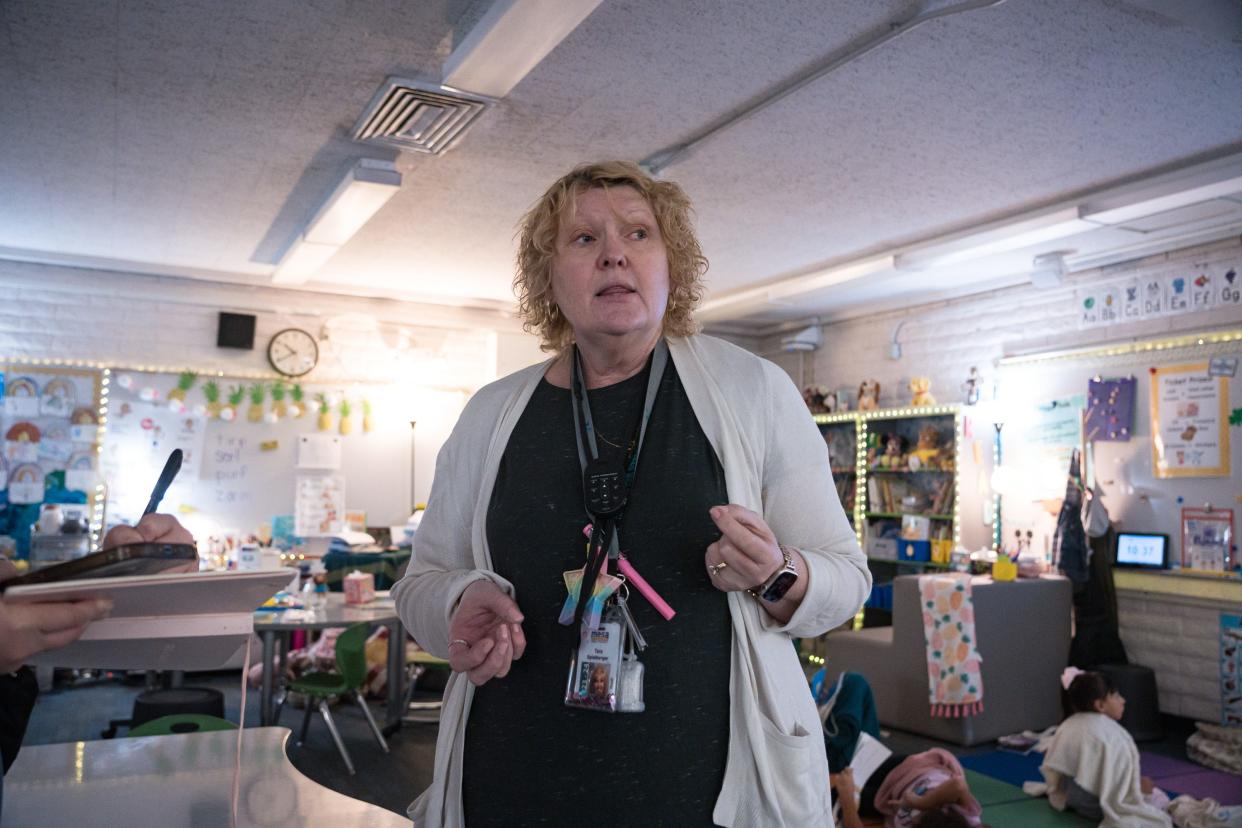

Is 83 first and second graders in the same room overwhelming for educators? No, said Tara Spielberger, lead teacher for the class. It's a blast. Sometimes the kids do morning yoga.

"I love family meeting," she said. "It's a lot of fun for the kids."

The goal of what ASU is calling the Next Education Workforce is to reduce teacher burnout, boost student achievement and encourage educators to stay in the classroom amid a teacher shortage. Measuring whether team teaching is successful will take several years, but ASU leaders say the data collected already is promising. Now, Michigan educators want to try it out, too, with at least one district, Concord Community Schools near Jackson, making plans to adapt the model for a school this fall.

"Teachers working in a team get to know students on a very personal level," said Rebecca Hutchinson, superintendent of Concord Community Schools, one of the superintendents who visited Arizona. "It feels more like a family versus a classroom and a teacher. So that type of relationship that's able to be built in a team allows for a sense of personalized learning and targeted support."

Teaching in teams

Team teaching isn't a new concept, it was a trendy idea in schools in the 1960s across the country, including in Michigan. Randolph Elementary in Livonia, along with other school buildings across southeast Michigan, was originally designed for team teaching, with folding walls, according to a Detroit Free Press article from 1966. A spokeswoman with the district says the school no longer has folding walls or uses a team teaching model. It's unclear why schools moved away from the model then.

But teacher shortages across the country have put the model back into focus, starting around 2019 when ASU first started helping schools execute team teaching models. Their work has expanded into 13 states and 30 different school systems since then, said Brent Maddin, executive director of Next Education Workforce.

Classrooms are structured in different ways depending on a school's needs. Teams of educators should meet regularly to track how students are faring and teams may not just contain certified educators, but also student teachers, instructional aides and even community members with special expertise volunteering on a part-time basis.

Having multiple adults work with a large group of kids offers more flexibility around what teachers can do for students, Maddin said. Teachers can focus on subject areas where they really excel, and can do more intervention with students who need it.

"In a one teacher: one classroom model, a teacher is trying to do it all," he said. "The moment that you have multiple educators together, you can ... group and regroup kids in all sorts of really interesting ways."

At Stevenson, students in the grades five and six class have a period called "What I need" baked into their schedule, so teachers can work on personalizing intervention, according to Lindsay Pombier, one of the class' teachers. On a Monday morning in her reading classroom, students circulate trying to answer questions about words with multiple meanings. (For example: the word "saw" could be the past tense for "see" or the tool used for cutting materials.) Then, students grab pillows or stools to read independently while Pombier watches.

Pombier likes focusing on reading, she said. Before, in a traditional teaching model, she struggled teaching students different subjects all day.

"In traditional, I taught all the subjects, I had kids all day, and it's overwhelming trying to do everything and be the expert in everything because I just wasn't," she said. "I love that we kind of share that load."

Tackling a teacher shortage

Michigan's teacher shortage is particularly complicated right now. While research shows high turnover during the pandemic and schools report particular shortages in subject areas such as special education, some districts are in a financial pinch, which is only forecast to worsen as federal pandemic relief money dries up. And, student enrollment at public schools has declined while staffing levels have increased.

Still, state leaders say retaining educators and attracting more into the field is important.

Jack Elsey's full-time job is working to recruit and retain more full-time teachers into Michigan's schools. Elsey, a former Detroit public schools assistant superintendent, is the founder of the Michigan Educator Workforce Initiative. Part of the organization's mission is to transform classrooms to encourage more educators into the profession.

"How do we transform the profession enough that people get interested in it?" he asked. "The more people get interested in it, more people stay. But then also, obviously, the big goal here is: How do we serve kids better?"

Elsey had heard about ASU's work in other schools and asked a group of Michigan superintendents if they'd be interested in experimenting with the way they staff their schools. Leaders from about seven or eight districts eventually made their way to Arizona and Elsey's team continues to work with interested school leaders about putting the model into districts as soon as feasible.

For Hutchinson, doing something new to retain and recruit new teachers is a critical need. In the next three to five years, roughly 50% of her teaching workforce will be eligible for retirement, she said. Concord is a rural district, where attracting teachers to the small community is hard work.

"We are losing not only a person to teach, but we're also losing that experience and knowledge about our district systems, which are unique to us," she said.

That's a concern for Dan O'Connor's district, too. O'Connor is superintendent of Alcona Community Schools in northeast Michigan along Lake Huron. Alcona, also a rural district, has a lot of veteran teachers who O'Connor wants to mentor the next generation in Alcona, and work with student teachers, teachers early in their career and even school employees motivated to get their teaching degrees to eventually teach in the district. For the veteran teachers, it's a path to a leadership role.

Team teaching might help Michigan districts "as our workforce changes and the experience levels are very different currently than then what they typically are," he said.

As a former teacher, Elsey liked that the teachers he saw in Arizona weren't siloed. When he was a first-year teacher, Elsey remembered feeling very isolated and making a lot of mistakes. He wished he could have had more mentorship.

In a team teaching model, he said, "I wouldn't have felt so lonely and isolated and frankly like such a failure as a teacher because I failed a lot in my first year."

Is it successful?

At Stevenson, state test scores have not increased among all grades, but the performance data may also be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, as students struggle to catch up, according to state data. Stevenson also largely serves students in low-income communities, and often student test scores coincide with poverty levels.

Maddin said ASU is particularly interested in measuring whether these models will impact student attendance rates at a time when chronic absenteeism across the country, including in Michigan, has skyrocketed.

"We need to be considering both educator outcomes and learner outcomes," he said.

Team teaching won't change school funding levels from the state, and won't solve what is often a major complaint among teachers, which is inadequate pay. But it may make teachers more satisfied with their jobs.

ASU is waiting on additional academic data to see how students have performed under team teaching models. A survey from Johns Hopkins University found educators collaborated more in the new setup, were more satisfied in their jobs and had more positive interactions with students, even though they saw more students in a day.

Stevenson teachers said the team model has transformed their workplace. Spielberger said she used to count the years until she could retire, after more than 20 years in the classroom. Now, not so much.

"I mean, still there's a lot of stress, there's a lot of pressure," she said. "But not like there used to be. I only have to develop one really good lesson a day. And I can focus on making that lesson the best that it can be as, whereas I was trying to spread myself thin over four or five different curriculums."

Mary Pierce, an ASU student set to graduate in May, has been a student teacher at Stevenson in the kindergarten classroom since the fall. On April 15, she read a storybook to the kindergartners and led the class, along with the head teacher, in a conversation about what she'd read.

Pierce likes that she gets to work with multiple teachers at a time and learn different styles.

"All of that has really helped prepare me as I go into my first year of teaching," she said.

Disclosure: The reporter teaches online communication classes at Arizona State University's communications school, but has no involvement with ASU's Teacher's College or the Next Education Workforce.

Contact Lily Altavena: laltavena@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan school district leaders are considering a new teaching model