8 reasons why Louisville (and not Lexington) landed more than $110 million from the state

In our Reality Check stories, Herald-Leader journalists dig deeper into questions over facts, consequences and accountability. Read more. Story idea? hlcityregion@herald-leader.com.

There was a lot of taxpayer money to dole out during this year’s budget session in Frankfort.

With overflowing reserves, the state legislature ended up spending more than $2.7 billion of it on one-time projects over the next two years on top of the $30 billion-plus two-year budget.

Though the budget is multi-faceted, the plainest comparison between the two city government’s is Louisville’s direct appropriation of $111 million to Lexington’s $10 million.

Lexington’s total could jump to almost $30 million, however, if one counts scheduled debt payments related to the state and University of Kentucky-run Eastern State Hospital.

How else did Lexington compare to Louisville in the budget? And why, when it comes to direct state funding, did the state’s largest city outpace the second-largest by much more than its population would suggest?

Here are six factors that could explain the difference in state funding between Lexington and Louisville:

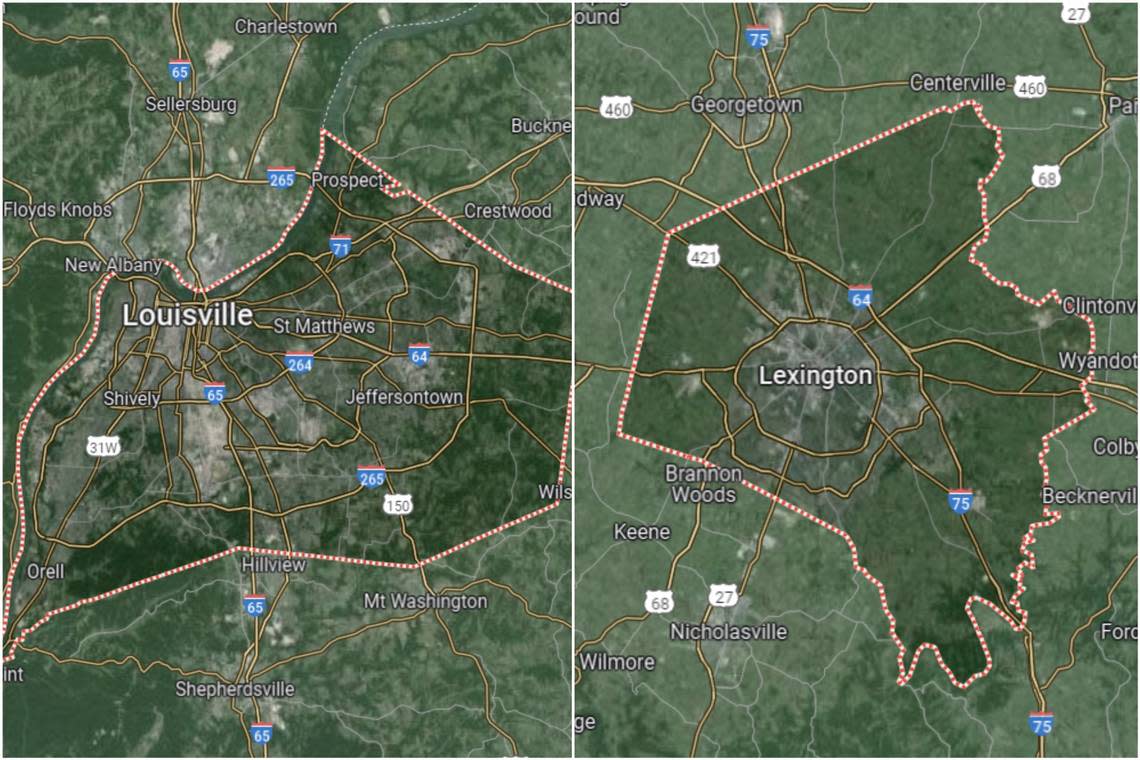

Density: When thinking about the disparity between funds dispersed in the state’s highway plan, Fayette’s density may play a role. Jefferson County is bigger, with 385 square miles to Fayette’s 284. However, Fayette County’s urban service boundary makes for a more densely populated area and less suburban sprawl, generally decreasing the number of roads in need of maintenance — same applies to sewer and water lines. Less than a third of Fayette County land is included within the urban service boundary, around 85 square miles. Sen. Amanda Mays Bledsoe, R-Lexington, who previously served on Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council said “(Density) is part of it. That’s a big part of it, actually,” when asked about road funding dollars.

Mayoral tactics: One Louisville legislator said Mayor Craig Greenberg proved the difference. Greenberg, a Democrat, made four separate trips to Frankfort and ingratiated himself with the Republican legislature much more than his predecessor. Gorton was comparatively much less visible this session, though she mentioned personally lobbying legislators for a couple road projects, one on Georgetown Road and another in Hamburg.

Lobbying: Like corporations or special interest groups, cities can pay lobbyists to advocate in Frankfort on their behalf. Both Lexington and Louisville did so, but Louisville spent much more. Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission records show that Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government spent $6,000 in the month of March paying a veteran contract lobbyist — however, records provided later by local officials show that they’ll pay the lobbyist $15,000 from Dec. 1, 2023 through Fiscal Year 2024, which ends June 30. Meanwhile, Louisville Metro Government and its sewer division spent almost $47,000 paying a full-time lobbyist, as well as several contract lobbyists with the group MML&K Solutions throughout the three months of the legislative session, according to Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission records.

Lexington’s relative success: Unlike Louisville, Lexington does not have an outsize homicide problem, it has not seen headline-grabbing departures from downtown office buildings, it was not the epicenter of unrest and protest over the police killing of Breonna Taylor in March 2020, its school district did not take a massive amount of criticism for bungling student transportation — for these reasons and others, legislators saw Louisville as in a unique position of need.

Louisville under the microscope: While the above issues may have contributed, some Democrats say that the extra attention from Frankfort isn’t always welcome. Democrats have pushed back against bills making local elections nonpartisan, freezing zoning laws, changing the local police force’s disciplinary process and potentially paving the way for Jefferson County Public Schools to get broken up. Lexington has seen far less direct intervention into local affairs.

Bluegrass Station: It became a political hot potato due to local pushback, but the plan to expand Bluegrass Station — the Kentucky National Guard-run heliport serving military contractors like Lockheed Martin — was once a major proposed investment right on the Fayette-Bourbon county line. It was initially backed by the governor and the House, which proposed giving it more than $300 million. A state-funded analysis predicted the project could have generated an additional 3,000 to 6,000 jobs, but both Beshear and area legislators grounded it after significant local backlash.

UK’s appropriation: Fairly or unfairly, Lexington is often seen as a college town. As such, some in Frankfort pointed to investments in the University of Kentucky, an economic engine for the region, as de facto investments in the Lexington community. It made out quite well in this year’s budget, netting $685 million in Fayette County-based investments compared to $374 million for University of Louisville’s Jefferson County presence.

Political Lines and Leadership: Lexington has one Senator strictly within Fayette County lines while Louisville has five. In the House, that figure is 5 to 15. Jefferson County’s state legislative representation relative to Lexington’s is greater than its population size would indicate. Further, two members of Republican leadership (the GOP controls the flow of legislation in Frankfort) live in Jefferson County and another lives just across the county line. No GOP leaders live in Fayette County, though Sen. Damon Thayer, R-Georgetown, lives close by and represents a slice of Fayette County.

Direct to local government state investments

Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government:

$10 million to support a public-private partnership referred to in the budget as Lexington’s “Transformational Housing Affordability Partnership.”

$19.6 million for lease payments to retire its debt for the construction of the new facility; the University of Kentucky runs the hospital, but part of the financing flows through Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government Public Facilities Corporation.

Louisville Metro Government:

$100 million for downtown revitalization.

$7 million to support the Shawnee Outdoor Learning Center.

$2.5 million for the Jefferson Memorial Forest.

$1.5 million for the Grand Lyric Theater.

Other state investments:

Fayette County:

$39 million for the Kentucky Horse Park (partially in Scott County).

$19.6 million for debt repayments on Eastern State Hospital, which is operated by the University of Kentucky.

$5 million for Blue Grass Regional Airport.

$4 million for the Aviation Museum of Kentucky, which is located at Blue Grass Regional Airport.

$100,000 to The Nest, a center for women, children and families.

Jefferson County:

$30 million for children and family crisis center Home of the Innocents.

$20 million going to Kentuckiana Works, a regional workforce partnership with headquarters in Louisville.

$12 million for Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts.

$5 million for Muhammad Ali International Airport.

$5 million for the Kentucky College of Art and Design.

$4.3 million for the Louisville Orchestra.

$4 million for the Waterfront Botanical Gardens.

$4 million for Harbor House, an adult daycare.

$3 million for the Goodwill West Louisville Opportunity Center.

$2 million for the Fern Creek Library.

$1.5 million for the city’s riverport.

Highway plan breakdown:

Fayette County

$116 million total.

$22.7 million in state-funded projects.

Jefferson County:

$494 million million total.

$83 million in state-funded projects

Reporter Beth Musgrave contributed to this story.