'Is $50 an hour the new middle class?': This Florida man on TikTok says Americans can no longer survive on $2,300/month — thinks wages for college grads are 'out of whack.' Is he right?

If you thought $15 an hour was a leap for U.S. minimum wage, wait until you hear how much this TikTok creator thinks you need to earn to be part of the coveted “middle class."

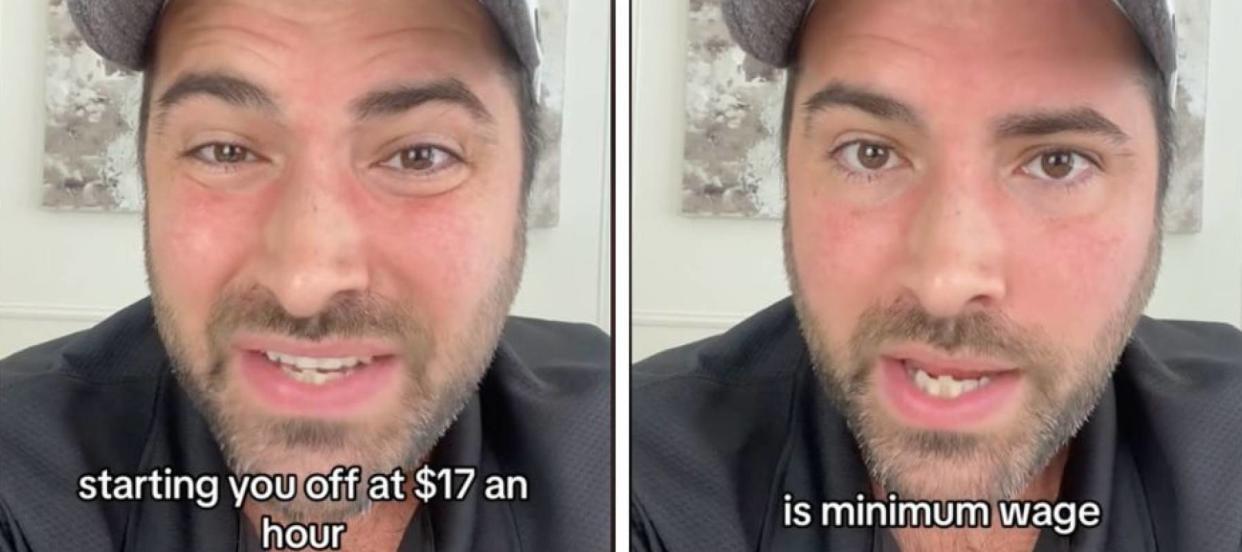

Freddie Smith went viral this week for asking a controversial question on TikTok: is $50 an hour the new middle-class wage?

Don’t miss

Millions of Americans are in massive debt in the face of rising rates. Here's how to get your head above water ASAP

Golden years security: Unveiling 2 powerful ways gold can safeguard your retirement wealth in today's uncertain economy

Big box stores are getting away with overcharging their customers — use this app to instantly get the best deals when you're shopping online

The Orlando-based realtor said that many people he knows work jobs requiring bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees, yet they only earn $17 per hour – $5 more than Florida's current $12 minimum wage, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

“People cannot survive,” he says. “That’s what[’s] out of whack, more than inflation.”

Comments on his video were split. Someone pointed out that it “depends where you live” for how far your wages can go. Another person said they make $50 per hour and are “broke.”

So is Smith right? Do you really need $50 an hour to live a middle-class life in the U.S.?

Here’s how the math stacks up.

The math

In his video, Smith calculates what $17 per hour gets you. One thing he calculates is that $17 per hour comes to a total of $2,300 a month after taxes.

He isn’t too far off. You’ll make around $2,720 before taxes at the lower-income wage of $17 per hour, which comes to $32,640 per year before taxes.

This salary puts this hypothetical person in a federal tax bracket of 12%, according to the IRS. If the hypothetical person lives in Florida, like Smith, they won’t have to pay a state income tax, according to the Florida Department of Revenue. So the person’s take home pay every month, after the 12% federal tax, comes to $2,393.60.

Comparatively, the middle-income wage $50 per hour comes out to an annual salary of $96,000 before tax and you fall into the 22% federal tax bracket. After tax, you’ll end up with $6,240 every month.

Let’s see how these two salaries stack up when you consider the monthly expenses Smith highlights in his video: shelter, food and child care.

Housing

Smith’s estimate assumes a hypothetical rent of $2,000 a month. He isn’t too far off. Rental platform Zumper reported that the median rent for a one-bedroom in the U.S. is $1,505.

If you own a home, the average U.S. mortgage payment is $2,317 a month, according to a 2023 LendingTree survey. This would essentially put homeownership out of reach for the lower-wage worker, but is possible for a middle-wage worker. However, there is a growing trend of rich Americans who are ditching their plans of home ownership in favour of renting, in part due to high home prices and mortgage rates.

If you think about the old adage that says housing shouldn’t be more than 30% of your income, then you can see the impact high housing costs are having on the budgets of lower-wage workers — and how, by that classic benchmark, many middle-income workers are now rent-burdened as well.

Read more: Super-rich Americans are snatching up prime real estate abroad as US housing slumps — but here's a sharp way to invest without having to move overseas

Food

In his video, Smith estimates that food costs $1,000 a month. This number is accurate if you assume multiple people are living in the household, but for one person, it appears to be an over-estimation.

According to a recent survey from moving company Move.org, the average monthly cost of food per person comes to $415.53. This means that lower- or middle-wage workers could at least put food on the table.

Even so, the BLS reports that food has jumped 8.4% since 2021 – and people are feeling it. Over 60% of Americans are struggling with putting food on the table, according to a 2023 report from research company Attest. Over 9% of people have “a lot of difficulty” affording food, but over 50% only have difficulty some of the time – which tracks with the average food costs above.

Child care

Smith says that parents pay around $2,000 a month for child care. He’s not totally off, but it’s around $833.33 per month, with child care costing on average $10,000 per child per year. Even though the numbers above for food and shelter assume a person lives alone, child care means that there’s at least one more person in the household – and that contributes to higher household costs outside of just child care.

Just that $833 for child care is too high a cost for that lower-wage worker to shoulder alone; and even for a worker earning almost three times as much, it’s still a significant portion of their monthly income.

However, if you factor in paying for two kids at the average rate ($1,666) or three kids ($2,499), then you’re starting to see how a lower-income worker can’t afford to put their kids in child care. Even a middle-wage worker would be spending nearly half their paycheck on child care if they have three kids.

So does it add up?

Just accounting for the average costs of rent for a one-bedroom, food for one person and child care for one kid, your total expenses would come to around $2,753.86.

Assuming the monthly incomes stated in the above examples, that worker making $17/hour will not be able to cover basic living expenses on their income alone. Someone making what Smith dubs the new “middle-class wage” of $50/hour (around $6,000 a month) can survive, save some money and have some fun.

So it seems that Smith is in fact on to something, even if his own estimates swing high.

The data shows a person cannot shoulder the country’s average monthly expenses alone if they make $17/hour and child care is involved.

Even without the added child care costs, the average single American living alone would only be left with a few hundred dollars for anything outside of food and shelter, including other bills like utilities and car insurance or any emergency expenses that might crop up.

This also means other possible monthly budget concerns like paying off debt or stashing away money in a savings account could be out of reach completely. And even those earning higher incomes are increasingly unable to do more than live paycheck to paycheck.

What to read next

Owning real estate for passive income is one of the biggest myths in investing — but here's how you can actually make it work

Escape boomer's remorse: Discover the top 5 'big money' retirement regrets and how to shield your future

Commercial real estate has outperformed the S&P 500 over 25 years. Here's how to diversify your portfolio without the headache of being a landlord

This article provides information only and should not be construed as advice. It is provided without warranty of any kind.