The 44 Percent: Drake v. Kendrick, FAMU donation & Caribbean Film Festival

Last week was arguably the best moment in hip-hop history.

Over a period of five days, two rap titans, Drake and Kendrick Lamar, traded diss after diss in what essentially amounted to a heavyweight bout. The feud had all the makings of a 21st Century beef: quick responses.; Artificial Intelligence; unsubstantiated tea about plastic surgery, pedophilia and domestic abuse (more on the last two later); immediate social media dissection.

But what started as mere jabs at the other’s height and hair soon became something more sinister as each rapper tried to one-up the other. On “Meet the Grahams” and “Not Like Us,” Lamar rehashed Drake’s alleged inappropriate behavior around minors and accused him of sex trafficking. On “Family Matters” and “The Heart Part 6,” Drake fired back that Lamar allegedly beat his partner and made fun of the Compton, Calif. rapper for allegedly having been molested (the last bit can be attributed of Drake’s misunderstanding of Lamar’s “Mother I Sober” in which he denies being sexually abused as a child despite his mother’s belief otherwise. Still, not good look).

Both rappers’ barbs, however, are not unique. In fact, they employed a common trope in rap beef: using women – primarily Black women – as lyrical darts to put chinks in the opponent’s armor. 2Pac claimed to have had sex with Faith Evans, the Notorious B.I.G.’s wife. Jay-Z essentially did the same thing with Carmen Bryan, the mother of one of Nas’ children. Drake himself even weaponized Nicki Minaj’s stardom against Meek Mill. The result: the autonomy of women gets stripped away amid a hyper-masculine, mudslinging for rap supremacy. Or as Andscape’s David Dennis put it, women end up as “both the nuclear bomb and the collateral damage.”

The truth is, neither rapper has the best track record when it comes to women. Drake declared a holiday for the release of his friend and OVO affiliate Baka Not Nice, who was accused of sex trafficking in 2014 yet had the charge dropped after the women refused to testify and subsequently pled guilty to assaulting another women in 2015. “The Boy” also has publicly supported Tory Lanez, who’s currently behind bars for shooting Megan thee Stallion, and even name checked Chris Brown in the same track that he accuses Lamar of putting hands on his partner.

Lamar isn’t much better: his former label boss Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith threatened to remove the West Coast rapper’s catalog if Spotify took R. Kelly and XXXTentacion off of its playlists. Furthermore, Lamar tapped Kodak Black, who pleaded guilty to first-degree assault and battery in 2021 after initially being charged with rape, to co-star on Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. Both rappers’ accusations in spite of their own behavior simply fall flat under criticism.

Nearly a week removed from the lyrical feud’s climax, it would appear that Lamar emerged victorious in the court of public opinion but at what cost? The accusations levied at two of the biggest hip-hop stars of the last decade are deplorable if true. “Not Like Us” is an early contender for song of the summer but how do we, myself included, as rap fans reckon with such flippant accusations of pedophilia? Why is it that when it comes to rap beef, women automatically become tools for the other’s destruction?

Sure, rap has made significant progress since its birth some 50 years ago. It’s impossible to deny that women really have been carrying rap for some time prior to last week’s nuclear rap feud. Rappers who identify as LGBTQ+ are more prominent now than ever – even if “Family Matters” has traces of homophobia. Lamar’s colonizer angle has even revived the important conversation about who can and cannot speak about the important piece of Black culture that is hip-hop. The last week was exhilarating to say the least, full of lyrical dexterity and quadruple entendres that will continue to captivate rap fans for decades. But now comes the important question: how can we move forward as a culture?

INSIDE THE 305

These five Black-owned restaurants in Miami just got $10,000 grants:

Smith and Webster. Rosie’s. World House of Mac. Lil Greenhouse Grill. House of Wings.

Big up the Black Innovation Alliance for awarding $10,000 to each of the five aforementioned restaurants.

“This is our way of saying we know Black businesses don’t get access to friends and family rounds,” said Black Innovation Alliance CEO Kelly Burton. “We don’t necessarily have inherent wealth. We need to find new ways to show up for each other and Black businesses.”

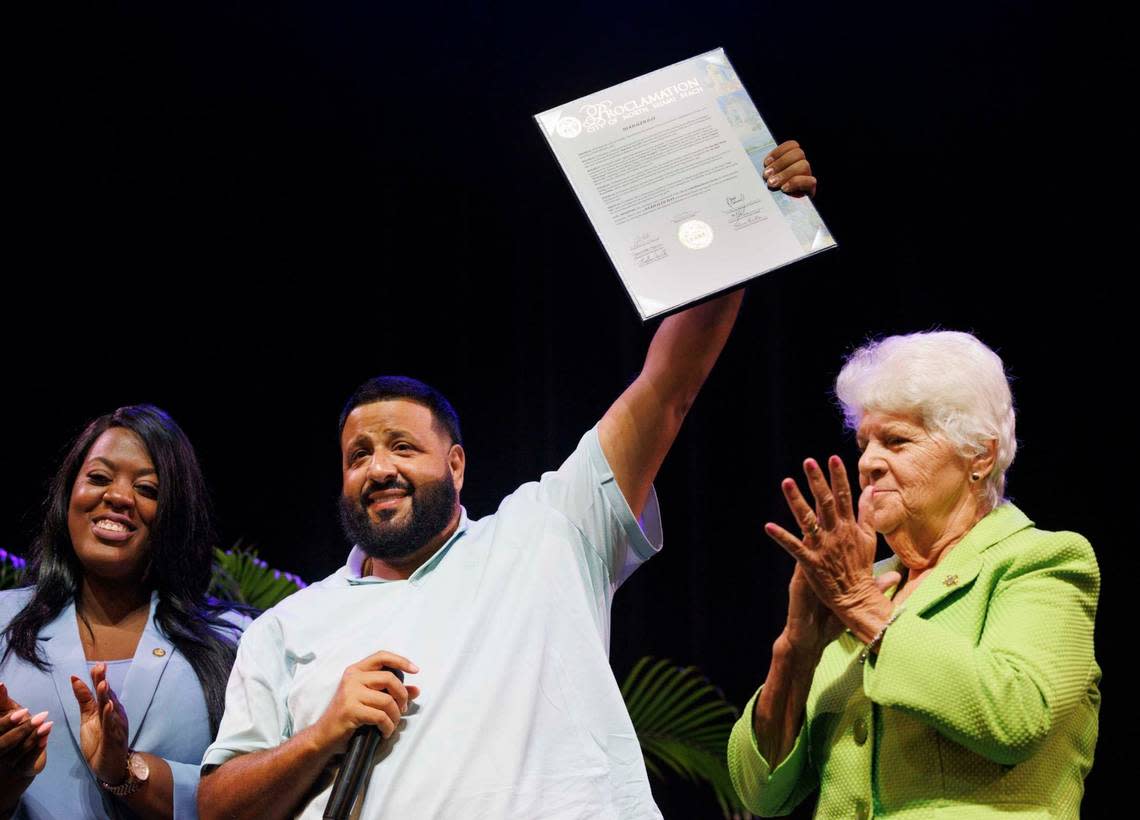

It’s not just any day. In North Miami Beach, it’s ‘DJ Khaled Day’:

North Miami Beach officially has a day for one of the 305’s biggest champions: Khaled Mohammed Khaled, known world over as DJ Khaled.

At Wednesday’s North Miami Beach Small Business Summit and Expo, the multiplatinum producer received a proclamation that declared May 8 “DJ Khaled Day.”

The proclamation made Khaled emotional as he reminisced about crafting most of his hit records in a North Miami Beach studio.

“This is very beautiful and means a lot to me and my family,” he said. “Big ups to all the mothers and fathers in the building today. This makes me inspired to keep going.”

OUTSIDE THE 305

A hemp farming executive just donated $237M to Florida A&M. His last college gift failed:

FAMU is in the news after its graduation speaker gifted the institution with the largest donation in historically Black college or university history.

Only one issue: Gregory Gerami, the man in question, previously promised a similar donation to Coastal Carolina University yet the deal never came into fruition.

Alumni and critics are asking who is Gerami, and whether this transformative gift is too good to be true, especially in light of his failed donation to CCU.

The public skepticism has grown loud enough that the university issued a press release Sunday, offering reassurances that it has “done its due diligence when it comes to this matter” followed by a Monday press conference with reporters.

“While a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) we signed prevents us from disclosing many details ... Mr. Gerami transferred $237,750,000 worth of stocks into our account last month,” the press release states. “As with any non-cash gift received, such as cryptocurrency, real estate, and stocks, it will be converted to cash and recorded appropriately.”

In a statement sent to the Tallahassee Democrat on Tuesday, FAMU board vice chairman said that he requested an emergency board meeting to learn more about the donation.

“A donation of this nature requires the highest degree of transparency and inquiry, and to this point that has not occurred,” Deveron Gibbons said in a statement to the Tallahassee newspaper.

Inside the Columbia University encampment:

This longform story, composed by the staff of the Columbia Daily Spectator student newspaper and published by New York Magazine, offers first person accounts of what actually happened at the university. What’s rather intriguing is that the encampment carried on a long Columbia tradition of dissent that even I, as an alum, was unaware of.

By refusing to leave unless Columbia committed to divest from Israel and cut ties with Tel Aviv University, among other demands, the students were acting in the shadow of 1968, when protesters dramatically took over buildings, including Hamilton, to resist the Vietnam War and the university’s racial politics. Those events established Columbia’s reputation as a hotbed of dissent where social and political change takes root before spreading to the rest of the country — often at great cost to the institution. As the school itself notes about ’68 on its website, “It took decades for the University to recover.”

HIGH CULTURE

This Miami film festival creates spaces for Caribbean filmmakers to tell their stories:

After a hiatus in 2023, the Third Horizon Film Festival is back for its seventh iteration. The in-person festival will take place May 9-12 while the virtual one will follow May 13-19.

A celebration of films that authentically highlight the Caribbean and its diaspora, the festival combines screenings and panel discussions that center on a region that’s often portrayed as an exotic playground in Western cinema. More than 20 countries will be represented across the festival’s nearly 40 films including the Dominican Republic (“Ramona”), Jamaica (“Coconut”) and Puerto Rico (“barrunto”).

“We wanted to make sure we were screening Caribbean films that were rooted in the ethics that considered the history of extractivism, the history of colonialism,” festival co-founder Jason Fitzroy Jeffers said. The films, he continued, didn’t “have to explicitly be about colonialism” but they couldn’t make “a spectacle of the region or conform to the dictates of Hollywood.”

Where does “The 44 Percent” name come from? Click here to find out how Miami history influenced the newsletter’s title.