After 43 years on the streets, Wichita police department’s ‘Dirty Harry’ retires

Chuck Loftis and another Wichita officer snuck on top of a pool hall at Ninth and Grove. It was the ‘90s and violent crime was skyrocketing as gangs fought over who could sell drugs where.

A spotlight on the building kept the dealers below from being able to see them. They peered down, saw an exchange for crack and called in the description of the dealer to officer Robert “Bob” Bachman, who was down the road in a marked police car.

Bachman pulled up. The dealer threw his crack and ran, but he didn’t get far, Loftis said. A man came out the door of the pool hall and yelled back inside:

“Dirty Harry got Bobby,” Loftis recalls the man saying.

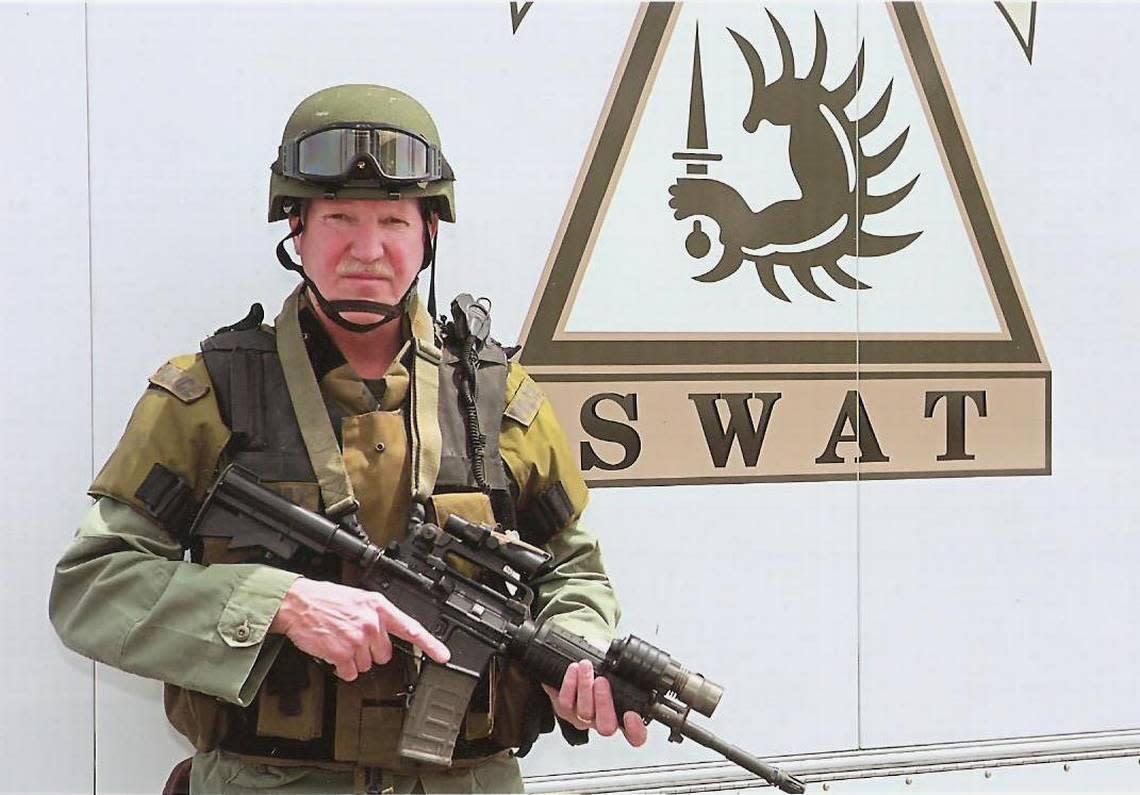

The nickname “Dirty Harry” — a fictitious tough cop made famous by actor Clint Eastwood — was given to Bachman during his 43 years on the force. In a callout of his retirement over the police scanner last week, a dispatcher said he was the “most highly decorated officer” in Wichita Police Department history.

Over those years, Bachman served on multiple specialty units and was an original member of the SWAT team. He created the department’s gang list. He earned numerous medals for his police work. And he was part of a small group of officers running to raise awareness for the Special Olympics that has grown into an annual event with global reach.

More than 100 people attended a retirement party for him Friday at the Wichita State University Law Enforcement Training Center. They shared stories about the 68-year-old and about the close calls they had together.

Kelly Otis, a former Wichita detective who helped catch serial killer BTK, said he remembers hearing Bachman got the nickname because he carried a .357 magnum that looked like Dirty Harry’s gun when he started with the department in 1980.

A 2012 Eagle article said he got the nickname from criminals “because he is six feet four, tough, obsessive, a marathon runner, a SWAT team member, a patrol officer who made more arrests than any other cop.”

With the name, Bachman said “the stories started about … me stealing drugs, robbing drug dealers.”

He added: “It’s just what they called me. A lot of them think my name is Harry Bachman.”

Not all will be sorry to see Bachman retire. For some, “Dirty Harry” symbolizes an outdated style of policing -- from initiating physical confrontations for low-level drug offenses to saddling people with the stigma of being on the department’s controversial gang list, which he started and kept on index cards in the trunk of his patrol car in the 1980s.

The list has since been digitized and expanded. It’s credited with helping build a federal RICO case in 2007 that led to the arrest of 28 Crip gang members and reduced gang crime for at least five years.

But the list also has drawn a lawsuit alleging it is unconstitutional and people can land on it without committing a crime.

“The northside can breathe now!!!!! Dirty Harry officially retired today!!!!!!” A.J. Bohannon, who organized a Black Lives Matters march about police killings nationwide and a cookout with community members and police that gained national attention, posted on Facebook.

Some painted Bachman in a darker light. Some Black residents feared him, and the department did not step in, according to a local pastor who would not be named for fear of retaliation from the department.

Floyd Powell, who became the department’s first Black chief in the late 1980s, said he had gotten complaints about Bachman, but he never disciplined him. Powell said the complaints were the type you’d expect for an officer working on special assignments with violent offenders.

“He really, really is a legend,” Powell said.

It was a career he never planned for.

Decades on patrol

Bachman was working construction during the winter in the late ’70s when insulated coveralls weren’t a thing. He needed something different.

At his mother’s suggestion, Bachman applied to work as a security guard at St. Francis hospital. He often interacted with police who would come to the emergency room. They told him to apply for the Wichita Police Department and he did.

Bachman was in his mid 20s.

He started working patrol downtown, but in a couple of years moved to the north bureau, where he worked patrol the rest of his career.

In the mid-1980s, crack cocaine swept through cities across the country. The cheap drug gave a powerful but short high, instantly making addicts who needed to keep going back for more. New and more customers left gangs fighting for areas to sell.

Gang wars were starting to drive violence in Wichita by the mid-1980s.

In 1987, the department started the SWAT team, Bachman said, but instead of calling it SWAT they put a bulletin up at work asking people to try out for a tactical team.

“And I was like, ‘what the hell is a tactical team,”’ Bachman said.

At his supervisor’s recommendation, Bachman tried out and made it, then stayed on for more than two decades.

The training came into play on two incidents: when an armed Vietnam veteran with a history of mental health problems got into a shootout with police and died in the Riverside neighborhood in 1992 and when a man held a woman hostage and then fired at police in 2003. Bachman was down the street when he fired his rifle; officers the man shot at fired back as well. The man survived.

Bachman and other officers received the Gold Award, which is given to officers who show “outstanding bravery, gallantry, or courage.”

At first, he said, SWAT would execute warrants with members riding around in the back of a pickup truck. Now they have multiple armored vehicles.

“SWAT has come a long way since then,” he said.

Bachman also served on what is now the department’s community response team, which does special assignments and executes search warrants. Loftis was Bachman’s supervisor on the team. He also told people at the retirement party about stopping someone who Bachman identified in the back seat of a vehicle as having a felony warrant.

It also happened around Ninth and Grove. It was around 2 a.m. and Bachman was driving. He whipped the patrol car around and told Loftis what he suspected. He was right.

Loftis, and many other officers, told how Bachman would remember incredible details about people, such as their addresses, associates and relatives. Officers would call him up for intel on people or to have him identify suspects who they thought gave them the wrong name.

In a 1990 story about crack sales at Ninth and Grove, women told an Eagle reporter that the youth didn’t come out to sell drugs until after 3 p.m. when Dirty Harry got off work.

“A lot of them knew it,” Bachman said about the time he got off.

Bachman said there would be drug deals in public when he hit the streets at 6:30 a.m., but they’d stop minutes after he’d start patrolling. He said the day shift allowed him to enforce in ways officers at night couldn’t because they were too busy.

“You didn’t drive down there at night,” he said. “It was wall-to-wall people. You would see a car pull up and eight guys would go over and try to make a sale. It was crazy.”

He said that area isn’t like that anymore. Gangs are now in different parts of the city, he said, and a lot of the drug problems have moved elsewhere.

“The ’80s and ’90s were crazy up in the northeast area,” he said. “Especially the 90s, you sit out at night and you hear gunshots all night long. It’s just really, really quieted down.”

In a 2012 Eagle article about how gang crime had been reduced after the federal case that landed dozens of gang members in prison, Bachman criticized how they lived.

“A lot of those clowns had spent years riding around in fancy cars, living the high life, having 10 or 15 kids with six or eight moms,” Bachman said. “Everybody in the neighborhoods knew who they were, knew they didn’t have real jobs, knew their money came from crime. That had an impact on people’s thinking.”

Bachman said a supervisor once told him to stop calling them clowns over the 911 police scanner. But that’s how he referred to gang members, he said.

It was also because Bachman knew what he described as “many of the thugs” that were doing the drive-bys that he was assigned to a drive-by task force. They responded to drive-by shootings like homicides, he said, and the number of those shootings dropped.

“It was very effective,” he said.

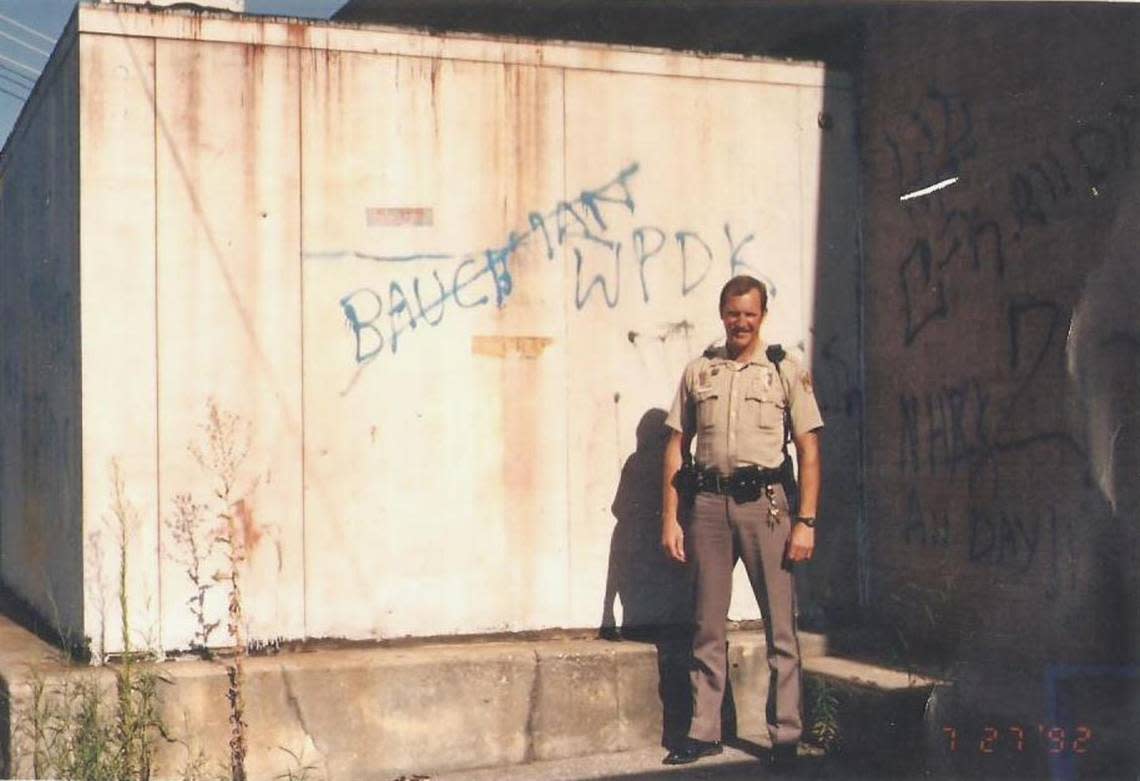

Bachman said he got death threats in the ’80s and ’90s. He’s seen areas where gang members would graffiti his name and then cross it out.

“You just be careful,” he said. “I was pretty careful. I was lucky too.”

Bachman worked the same area of patrol in north Wichita for decades. Early on in his career, Bachman asked a senior officer why he didn’t take a promotion, why he kept working the streets.

“And he said, ‘cause I don’t want to read about it. I want to do it,”’ Bachman said. “That’s been my philosophy since.”

Outside of enforcing crime, police said he was also passionate about mentoring his peers. More than a dozen people raised their hand when asked if Bachman had mentored them.

Passing the torch

Bachman said the greatest legacy of the department is its role in starting what became the Law Enforcement Torch Run for Special Olympics, a global effort with more than 100,000 officers taking part around the world.

In 1981, Bachman and five others ran from city hall to South High School to raise awareness. Included in the group was then-chief Richard LaMunyon. He eventually persuaded the International Association of Chiefs of Police to support the event. The organization is expected to have brought in $1 billion by the end of the year, LaMunyon said.

Bachman, who LaMunyon calls “a cop’s cop” and “the beat buddy you want,” plans to continue taking part in the annual race.

He also still plans to work reserves for the department and continue training officers in defensive tactics.

But it’s time to hang up his gun belt.

“As it slowed down, I slowed down,” he said. “I don’t jump out and chase people very often anymore … you chasing down a 25-year-old kid and you’re 65, it’s not a real competitive race. I used to be able to chase people a long ways. Being a cop is a young man’s game to a certain extent.”

The crime rate has started to creep back up in Wichita in recent years, but Bachman said he sees the next generation ready to take on the challenge. He said there are some young officers in Wichita on specialty assignments “hustling.”

“Doing what I did back in the day.”

Contributing: Chance Swaim of The Eagle