You Need a 3800 HP V-8 to Break 500 MPH

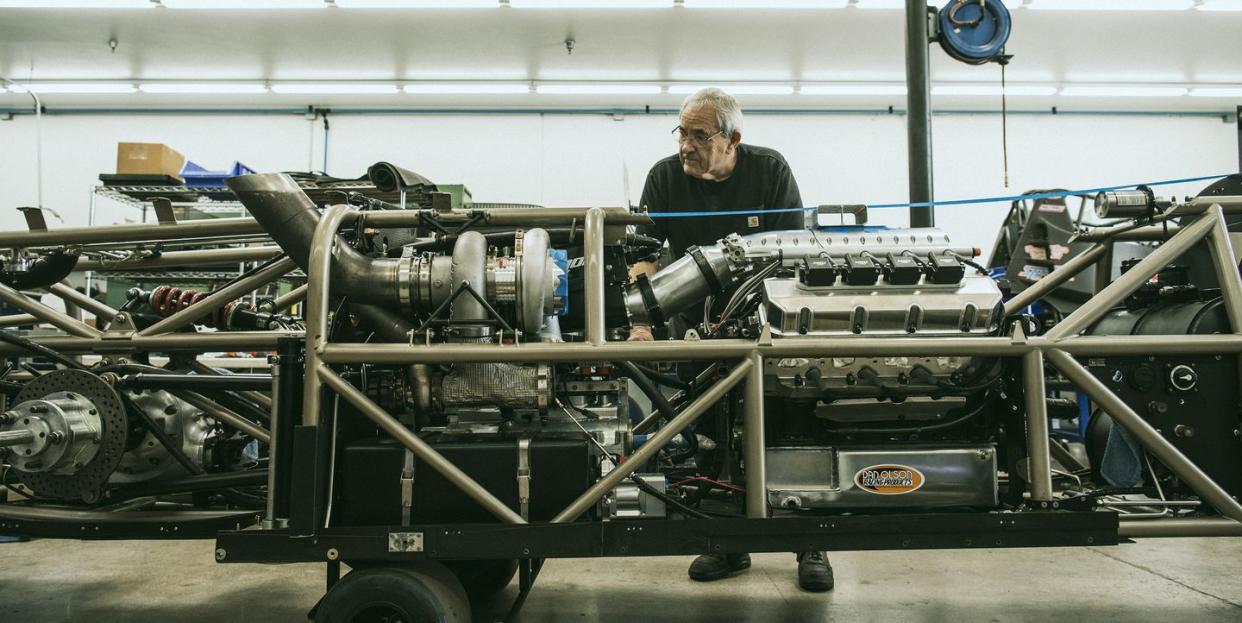

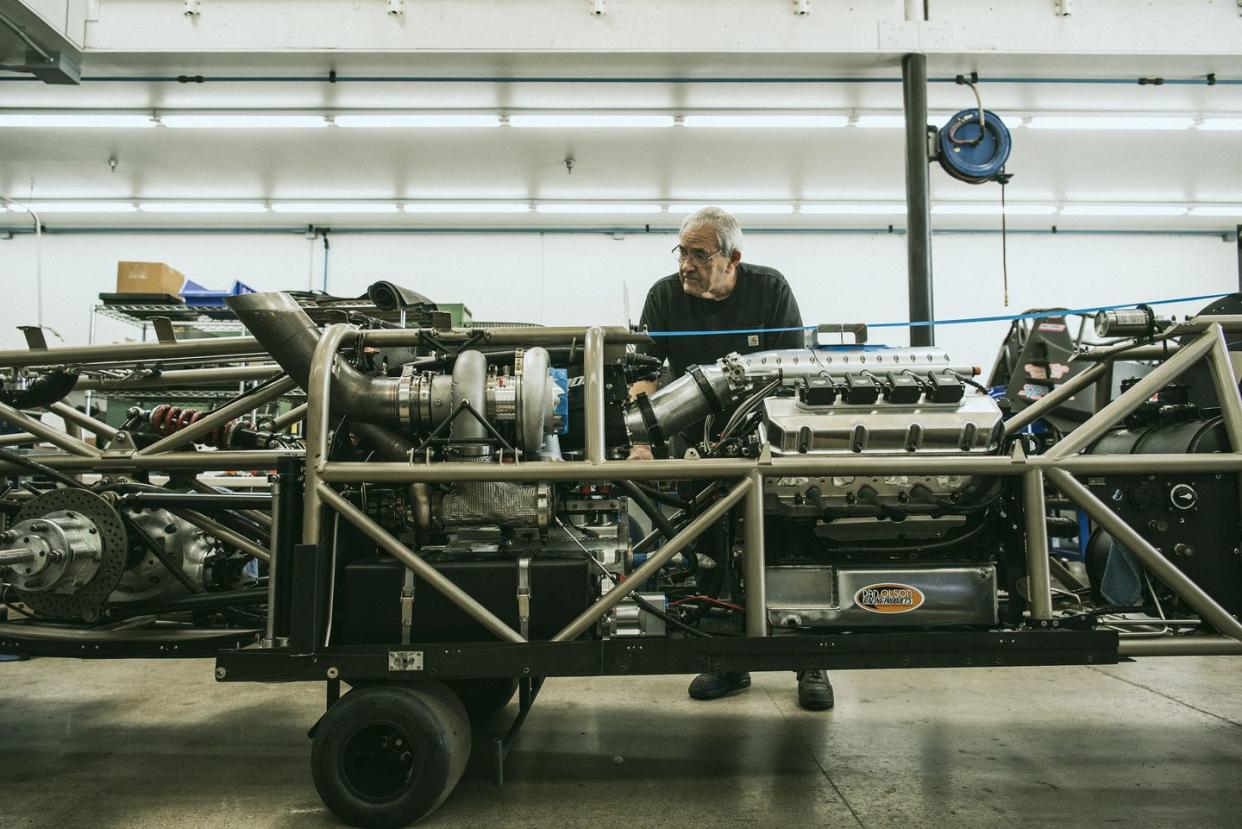

A 500-mph car doesn’t run on willpower or good intentions. Nothing about it is standardized. It’s all hand-built, every element demon-tweaked and optimized. Compromise isn’t an option. Any screwup will be catastrophic. Faith motivates, but science guides decisions. And the scientist building the massively turbocharged 560-cid V-8 engine is 83-year-old Kenny Duttweiler.

This story originally appeared in Volume 12 of Road & Track.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

“We should get 3800 horsepower out of the big engine,” Duttweiler says with the enthusiasm of someone in thrall to his work. “So if the salt is right and the weather is good and the engine does everything it’s supposed to, the car should go 500 mph.” He rocks back in the beat-up chair behind the beat-up desk in his tiny beat-up shop office in a well-aged cinder-block building behind a sandwich shop in Saticoy, California. “I know that’s what George wants.”

Speed Demon, the streamliner Duttweiler’s “big engine” is destined for, is already the fastest car ever powered by an internal-combustion piston engine—481.576 mph is the official record set at the Bonneville Salt Flats in August 2020. Its owner, George Poteet, now 74, was driving.

That’s 706.3 feet per second, or just shy of two football fields including the end zones. In a second. At 500 mph, replace the “just shy of” part with “more than.”

Duttweiler managed about a semester at Ventura College before turning to full-time automotive obsession. “One of my classes was auto shop,” he recalls. “And the teacher was a real goofball. And one day he said, ‘You know, the only way you can fix something is to understand how it works.’ A lightbulb went off, and I thought, ‘Oh, shit. I wouldn’t have to change a part if I knew how it worked. I might just be able to fix it or work around it.’ Those were words of wisdom. They hit me. At 18 or 19 years old, you don’t have much of a brain anyway. So that gave me forward motion and curiosity. I never went back.”

That’s community-college shorthand for the philosophy of science, Aristotle for grease monkeys. Working at his dad’s Shell station across from where his shop is currently located, Duttweiler grew increasingly obsessed. He read every gearhead mag he could, tested every claim on his ’57 Chevy, and soon racked up wins across Southern California drag strips. And in the late Fifties through the Sixties, there were a lot of drag strips in the region.

Saticoy, however, is in Ventura County, north of where the hot-rodding industry had become embedded. “I wasn’t around any of those hot-rodder guys to enable me to get smarter quicker. So I kind of had to do my own,” Duttweiler says.“When you dyno an engine, you always hope you can prove or disprove some theory. You don’t mind testing an idea that proves out wrong, because that idea could lead you to all sorts of other things. Otherwise, you’d never get there from here.” Duttweiler’s isolation insulated him from ossified conventional wisdom.

That was most apparent in the Eighties, as electronic engine controls and fuel injection took hold in production cars while many racers and rodders stubbornly stuck to carburetors. When Buick brought out the sequential-injected and turbocharged V-6 during the 1984 model year, Duttweiler became the master of the new engine. He was among the first to exploit the potential of turbocharging in drag racing.

With hundreds of engines assembled, Duttweiler’s exploration of internal combustion became a reward in itself. At one point, looking at the more than 300 trophies stacked in his shop, he decided to clear them out. “I threw them in the dumpster,” he recalls. “I guess they just didn’t mean that much to me anymore.”

Packaging a big, intricately plumbed, turbocharged V-8 engine into a thin streamliner is the sort of technical challenge that excites Duttweiler decades past retirement age. It’s not just bolting together parts but also understanding what’s happening inside the engine—reading the numbers generated on the dynamometer and seeing a story of valve actuation, compression strokes, and air forcing its way through intakes and turbos—and finding some way to keep it all hanging together for a five-mile blast across a dry lake bed in Utah.

Theoretically, the four engines Duttweiler has built for this year’s Speed Demon salt assault are based on GM designs. Two are based on the classic small-block V-8 architecture (256 and 368 cubic inches), another is sort of an LS (443 cubes), and the big one is a short-deck big-block V-8. But there’s not a GM part number on or in any of them.

Kenny Duttweiler has pondered and tested every element of all four. Hands are, after all, only as good as the mind to which they’re attached.

There’s greatness like this behind the roll-up doors of old cinder-block buildings all over the world. Only sometimes near sandwich shops.

You Might Also Like