There are 340 North Atlantic right whales left. A small underwater robot could save them

Like a dance, a right whale calf twirls and loops around its mother, nearly touching her with every graceful glide as the two take on the sea as though they’re the only ones in it.

“Frolicking, snuggling, swimming around,” said Catherine Edwards, Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, University of Georgia, professor as she plays the heartwarming video of the two.

Continuing to flit by its mother, the calf flapped a fin against her and sprayed water everywhere as it exhaled. The young right whale, scientists named Smoke, has “no idea about what it’s about to get into,” Edwards continued.

It’s a life spent in peril. One where the mammals leaving their summer homes in New England for their winter stays off the coasts of Florida and the Carolinas for their calving grounds, are susceptible to boat strikes and entanglement. The bustling ports of Savannah and Charleston pose threats to the migrating right whales, a place where large ships are cautioned to slow at the sight of these gentle giants but don’t always comply.

The stark reality of these threats is grim. In recent years, the North Atlantic right whale population has dwindled to 340.

Similar baleen whales, such as the Southern right whale, have bounced back since whaling stopped, said Erin Meyer-Gutbrod, co-researcher and assistant professor at the University of South Carolina. But the North Atlantic right whale population has never “bounced back,” she added, because “they’re constantly facing human threats.”

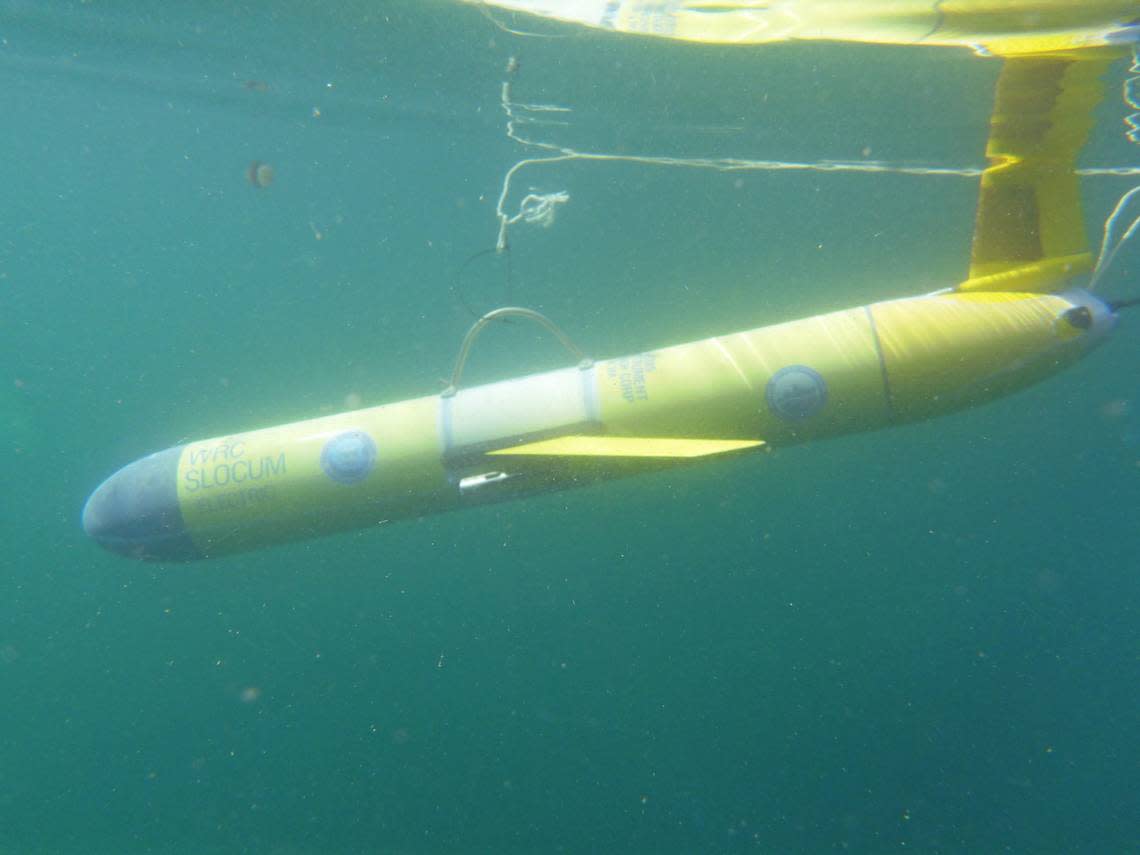

For Edwards and Meyer-Gutbrod, one solution to saving right whales lies in a relatively small machine that’s torpedo-shaped and moves like a wave underwater. It’s called a glider and it can provide what Edwards called a “fire hose” worth of data. But simply put, and for the purpose of studying right whale conservation, the device’s hydrophone detects whale vocalizations in real time.

Every four hours, the glider surfaces and sends the scientists data, allowing them to identify whale sounds and the mammal’s location. Once they parse the data for accuracy, they send alerts on various websites that ship captains can access to see where a right whale is present.

In the 15 days Edwards and Meyer-Gutbrod’s glider, dubbed Angus, was at sea north of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, it detected eight whale vocalizations.

If she could have it her way, Edwards said the team would “build up a fleet” of gliders. But for now, she and Meyer-Gutbrod, who are the first in the Southeast to deploy a glider to listen for right whales, are just getting started.

What’s happening to the right whales?

Centuries ago, right whales came by their name for all the wrong reasons.

Whalers called them this because the massive, slow-moving mammals that liked to hang out near the shore were the “right” ones to kill. Processing them for their blubber was easy for the whale hunters because the multi-ton animals float when they’re dead, Meyer-Gutbrod said.

Whaling decimated the North Atlantic right whale population.

More recently, over a decade ago, there were 500 of the animals at peak population. By 2017, that number had nose-dived, with mainly vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear to blame. That year, 17 right whale carcasses were found, an exorbitant amount compared to the three or four that are found annually.

The reason? Meyer-Gutbrod said because of climate change, the whales’ food source is moving to different waters — shifting from the Gulf of Maine northward to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The whales, of course, followed.

Continuing to keep an extra eye on calving grounds off the Florida and Carolina coasts is vital, Meyer-Gutbrod added, because if feeding locations up north are changing, so could the places right whales give birth.

“When right whales go places we don’t expect them to be, we don’t have protections available,” she said. “We’re not slowing boats down. We’re not modifying fishing gear or restricting fisheries seasons.”

Already vessel compliance is low when it comes to federal law that says all regulated vessels 65 feet or greater must travel at 10 knots or less in specified areas between Nov. 1 and April 30 to protect the species from ship strikes. Compliance rates of Savannah and Charleston harbors are “consistently below 5%,” according to marinewhale.com.

Beyond the need to push for enforcement of speed zones, locating right whales is another layer of keeping them safe.

That’s where gliders come in.

A powerful tool

To Meyer-Gutbrod, her co-researcher Edwards is a “glider wizard.”

She knows the nuances of the bright yellow robots that can measure the water’s saltiness, depth and chlorophyll levels, and pick up acoustics, all while slowly and quietly moving under water.

While it’s not entirely clear, Edwards said the glider can detect sounds up to a 10-kilometer radius. However, shallower waters in the Southeast and the enormous tides can limit the reach.

“It’s a pretty cool instrument,” Edwards said. “It’s a little less cool when it’s doing something unexpected in the morning and you’re sitting on your sofa, desperately trying to get it OK enough so you can go back to sleep, and then you catch yourself and you’re like, ‘Wait a minute, I’m sitting here talking to an instrument that’s 50 miles offshore.’”

Every four hours, the glider surfaces and sends data via satellite. It has its own learning algorithm to pick up whale sounds, but Meyer-Gutbrod and her graduate students analyze it themselves to verify each detection. When they nail down a detection, alerts are sent to Robots4Whales, Whale Alert and Whale Map, websites and apps where ship captains can see whether there are nearby right whales.

Alongside the glider are three stationary hydrophone moorings that listen for whale vocalizations.

However, the gliders can be persnickety, Edwards said.

Angus, the glider that Edwards and Meyer-Gutbrod set off to listen for right whale vocalizations, spent 15 days out at sea in late-January and early February. Its mission stopped because of a malfunction and it was stranded at the surface.

But even with the gliders’ sometimes fussy functioning, deploying one is far less expensive and much more convenient than aerial detection — from a plane or on a boat. Gliders can run 24/7 and persist through bad weather. Each glider costs $250,000 and costs $100-$200 a day to operate. Whereas, the RV Savannah, the research vessel UGA’s Skidaway Institute uses, ran the state $3.2 million and daily operating costs come in between $13,000 and $14,000.

Albeit testy, in the time Angus was deployed, the machine picked up eight times a right whale vocalized.

That’s eight instances in about two weeks that researchers were able to alert for the endangered mammals. It’s particularly important when it comes to female right whales migrating during calving season.

“Truthfully, the loss of a reproductively successful female whale is much more devastating to the population than the loss of a male,” Meyer-Gutbrod said. “And that’s what we have right here — reproductively successful females migrating here to the Southeast U.S.”

Ideally, researchers would like to see a third adult female right whales come down and give birth, because it takes about three years to complete a reproduction cycle. But that clockwork timing isn’t happening. It’s taking longer.

Meyer-Gutbrod points to right whales having trouble accessing their food source, which means they can’t build enough blubber for successful reproduction. It could also be stress or entanglements that make it more difficult to forage.

“We definitely know these females are giving birth much less than they could,” Meyer-Gutbrod said.

Moving forward

If furthering right whale conservation went her way, Edwards would love to see a dozen gliders dotted off the Southeast coast during calving season, watching the mammals migrate south and back north.

Leaving gliders out year round would mean a combination of sensors could give researchers richer data sets to identity everything from whale calls to hurricane intensification. They don’t need to be siloed into one scientific role, Edwards explained.

While gliders, weighing just a little over 100 pounds, are a vital piece of the puzzle in conserving endangered mammals that can tip the scales up to 70 tons, human behavior needs to go hand in hand.

“We can try to understand the science, but what are the policy solutions that can best protect the 340 whales left?” Edwards posed. “How do we make it so that ship captains and even smaller vessels are more likely to think about it? Are we relying too much on passive data-sharing ... versus what are the things that these vessel operators need, or what are the things that would make them change?”

But that’s social science. Edwards is sticking to oceanography.

The next glider mission? She and Meyer-Gutbrod have their sights set on December