28 artworks mysteriously disappeared three decades ago. They’ve finally returned home to South Africa

It was a phone call that changed everything.

“We have some good news.”

Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi had been waiting to hear those words for more than 30 years. It was May 2023, and the celebrated South African artist, by then 80 years old, could barely believe it.

“Your works in Sweden have been found.”

Sebidi let out a scream. “My babies, my babies,” she said into the phone.

She was referring to her artworks. Mysteriously lost in 1991, they were coming home at last.

Origins of an artist

Sebidi was born in 1943 near Hammanskraal, South Africa, north of Pretoria. Her mother had moved to Johannesburg to work as a domestic worker, leaving her daughter in the care of Sebidi’s grandmother, whose traditional painting style would become a major influence on her future.

“She taught me how to do it,” Sebidi recently told CNN, adding she would sometimes surprise her grandmother with a piece she’d done on her own.

Sebidi left school after grade eight to take a job as a domestic worker while also learning dressmaking. Any money she made, she sent home to support her grandmother.

It was not until 1970, in her late twenties, that Sebidi would take her first official art classes, learning painting and sculpting. Her instructor was John Koenakeefe Mohl, one of South Africa’s pioneering Black professional artists and teachers.

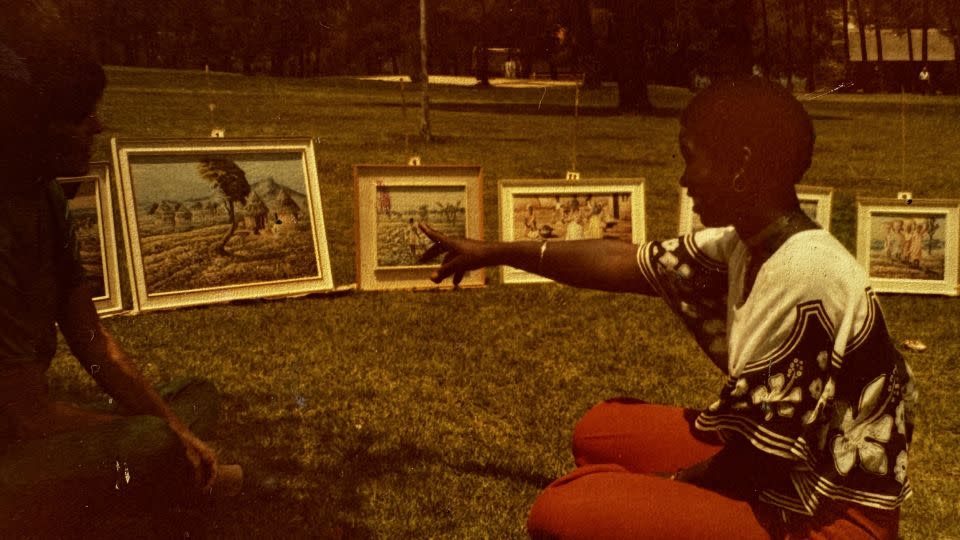

Under the umbrella of the Johannesburg Art Foundation, an organization aimed at supporting practicing artists who were not able to go to university, Sebidi would display her works under a tree, once a month, together with other artists in what was called “Art in the park.”

“People would go and look at mainly terrible stuff but very, very occasionally – almost never – an extraordinary artist would emerge,” said Mark Read, chairman of the Everard Read Group of Galleries, which now represents Sebidi. “Helen is the grand luminary figure who emerged from the Johannesburg Art Foundation.”

Her talent was evident from the beginning, Read recalled. “There was never any guiding needed with Helen Sebidi,” he added. “The opposite was always the case. She now and then thought that we needed guiding, which is probably entirely correct.”

Against the backdrop of apartheid policies in South Africa throughout the 1970s, Sebidi continued to refine her craft and find her voice, often depicting traditional imagery from a time before colonialism would grip the continent.

An invitation in 1985 to showcase her work at the Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA) sparked widespread attention for her work. It was her first solo exhibition and a first for a Black female artist.

It was a moment that would change the trajectory of her career. Four years later, Sebidi received a Fulbright Scholarship to travel to the US and continue her art at the prestigious Millary Colony for the Arts in New York state.

“My child became my work”

Yet it was an opportunity in Sweden in 1991 that would result in a most unexpected turn of events.

As part of a program designed to introduce the world to rising South African artists – who would in turn have an opportunity to meet and establish contacts with Swedish artists – Sebidi accepted an invitation to the Swedish city of Nyköping to exhibit a series of paintings.

Her trip would involve a one month residency where she would share South African knowledge with students at Nyköping Folk High School – just as South Africa was on the brink of democracy.

“It was a very vibrant time for the visual arts in South Africa,” said Kim Berman, a professor of visual arts at the University of Johannesburg. “People were really excited about imaging what a new democracy looked like; corporates and organizations wanted to buy young artists’ work, put it on their wall, and take down the kind of impressionist European posters.”

Two years before her Nyköping trip, Sebidi was involved in a serious car accident where she almost lost her life. During the incident, she says she received instruction in the form of a vision with a woman’s voice to paint the body of work that would become the collection she’d exhibit in Sweden.

“I was dead in that car accident,” Sebidi recalled. “The women, the voices came from deep green, very deep green and the road I wanted to go to my mother, was black, black, black, and the other side was this strong, beautiful forest.”

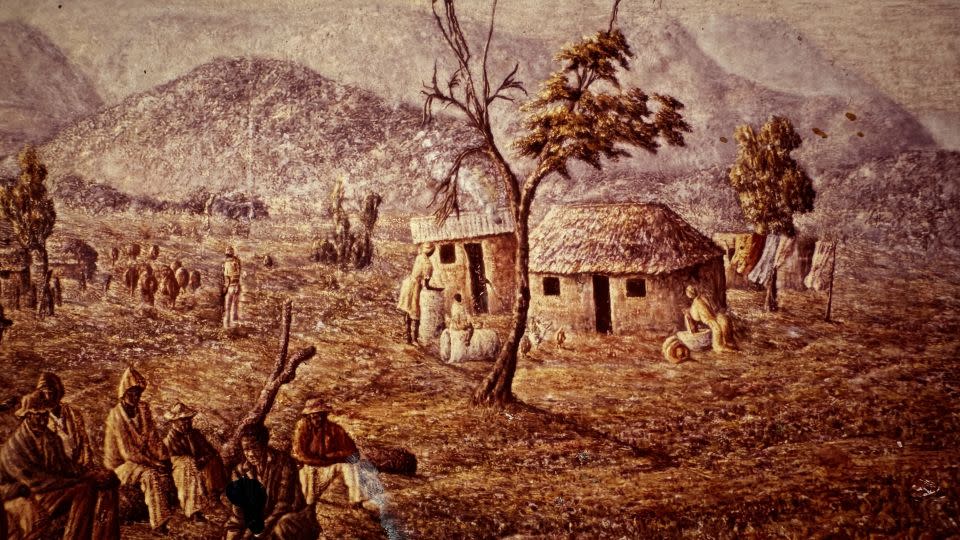

Sebedi worked tirelessly to produce work that would tell the story of her lived experience, and that of Black South Africans. Compelled by her grandmother’s voice and that of her ancestors, she called the collection “Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House).”

Although Sebidi never had children of her own, her art filled her life. “My child became my work,” she said.

A devastating mystery unfolds

The paintings were all made over the course of about a year, where she couldn’t sleep. Sebidi was haunted by visions and continued to work, her ancestors speaking to her saying, “your work is not done, get back to your work,” said Gabriel Baard, the curator of Sebidi’s most recent exhibition in Johannesburg.

“Before this kind of period between 1990 and 1991, (Sebidi) was working quite monochromatically. She worked in etchings and liner cuts, occasionally silk screens,” he added.

Contrary to her usual technique, these new paintings exposed “a reflection on her emotional state at the time. They are frantic, and fast and you can see the hand movement throughout every single drawing; an expression and an outlet to deal with her trauma,” Baard described.

With her artworks unframed and wrapped in rolls, Sebidi traveled to Sweden in 1991. As another artist was currently exhibiting, the curator at the school behind the project assured her to leave them in his care, and he’d call when it was her turn.

That call never came.

After a year went by without any communication, Sebidi requested her work be returned. But she was told that it had gone missing – believed to have been stolen.

Over the years, she exchanged numerous letters with the organizers, but it was all in vain. She says the pain of losing her “children” pushed her to “work harder and harder.” She became a figurehead representing Black women as a mentor in South African arts.

“There were textbooks written about her – she was included in the curricula for many of the schools,” Berman said.

Her other works were exhibited all over the world, including the Smithsonian in the US. In 2004, she was awarded the Order of Ikhamanga by former South African President Thabo Mbeki – among the country’s highest honors, given to those considered “a national treasure.”

But all the attention and accolades in the world still could not bring her missing paintings back home.

The homecoming

In May 2023, while cleaning out a cupboard in the attic of Nyköping Folk High School in Sweden, caretaker Jesper Osterberg discovered a large paper roll with Sebidi’s name, and a marker that indicated it had traveled from Johannesburg to Stockholm, on Swiss Air Freight.

It was the majority of Sebidi’s missing “Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House)” collection, 32 years after it was lost.

Baard traveled to the south of Sweden to collect the 28 found pieces and deliver them back to Sebidi.

His first encounter with them was very emotional, he said, seeing this body of work that had been missing for over three decades.

“I saw the faces actually at the top of the triptych kind of peering out to me,” Baard described. “It was transcendental and spiritual as I watched the work come to life.”

With great excitement and anticipation, Sebidi rallied her whole community, family and friends to welcome the pieces back home.

As she unrolled her work for the first time in 32 years, onlookers gasped in amazement.

“The work was truly timeless,” said Read. “Looking at it, one couldn’t say with any degree of surety what era it was from; inevitably that will mean that in the future it’ll also be just as fresh.”

A new generation

On April 6, “Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House)” went on display to the public for the first time at the University of Johannesburg Art Gallery, in partnership with Everard Read Gallery and the Swedish Embassy in Pretoria.

The paintings illustrate tumultuous groups of figures sometimes tumbling upon each other like a continuous dance. The colors feature shades of orange and deep reds, with thick paint on handmade paper that was sometimes torn and stuck on top of each other, adding texture and character.

Though there are still four small oil paintings missing, Sebidi is content with having her “children” back home and accessible for a new generation.

She says she believes that her work “was hidden by those ancestors wanting the current generation to prepare ourself for the bigger voice, bigger energy.”

Reflective of the “Ntlo E Etsamayang (The Walking House)” shaped by her grandmother, Sebidi hopes her work will influence the university to teach its students about indigenous knowledge.

“African knowledge systems need to be created and have to be launched and have to be in free places,” Sebidi said. “We need those freedoms.”

Mmakgabo Helen Sebidi’s exhibition is on display at the University of Johannesburg Art Gallery until May 17, 2024.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com