$20k? Homeowners in some Sacramento neighborhoods are billed more for sidewalk repair

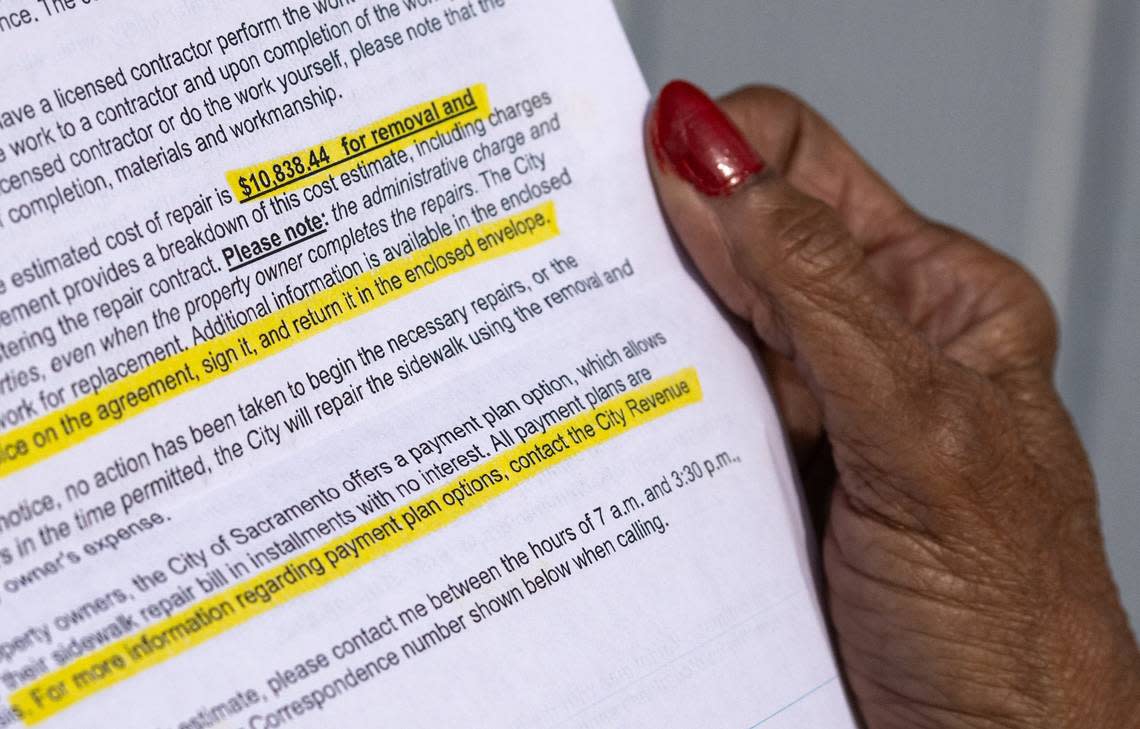

Ola Gipson thought the city must have made a mistake earlier this year. She received a bill in her mailbox for $10,383 to repair cracks in the sidewalk outside her Valley Hi home.

“They trying to give us a heart attack,” Gipson said. “How are you gonna blame us for the cracks? It is not that bad and I don’t think we should have to pay it at all. I asked them to waive us because we’re seniors, but no.”

Gipson, 73, is a U.S. Postal Service retiree. She and her husband Charles bought the home, on the corner of a quiet residential street in 1999, and are on a fixed income, she said.

In just under two years, the city has sent bills to 2,300 Sacramento property owners charging them about $8 million to repair sidewalks outside their properties. The ownership of the sidewalk in front of a home gets confusing because the city — and thereby its residents — holds a right of way to use them. However, state law dictates that owners of lots “shall maintain any sidewalk in such condition that the sidewalk will not endanger persons.”

Single-family and duplex homeowner bills range from a few hundred bucks to nearly $20,000. A disproportionate number of mandatory sidewalk repair bills go to property owners in the city’s economically disadvantaged areas, such as Valley Hi, Meadowview and Noralto, according to a Sacramento Bee review of city and census data.

About 56% of city sidewalk repair invoices since January 2022 went to property owners in census tracts where the median income is lower than $79,000, which is roughly equivalent to the citywide median income. Repairs in these poorer areas tended to be more expensive. The bill for repairs in those neighborhoods was roughly $4.9 million, or about 61% of the amount billed by the city. The average invoice in poorer areas was about $3,800, or about 5% of the annual income of a household earning the median for the city.

For commercial parcels, the bills go all the way up to $75,903 for a single property. That includes properties owned by large out-of-state corporations but also small business owners, such as Oak Park’s Plant Foundry, which was hit with a $15,000 bill earlier this year.

The Gipsons ended up hiring a private contractor to fix the sidewalk so the city will not place a special assessment on the property. But dozens of other Sacramento property owners have special assessments now, due to unpaid sidewalk bills.

For the fiscal year that ended in June, the city placed special assessments on 132 properties ranging from $60 to $7,000, according to a city staff report recently submitted to the City Council.

Homeowners with unpaid special assessments can be penalized the same way as if they have unpaid property taxes. If taxes are not paid, the county fines the property owner. After three or more years of delinquency, the county could sell the property in a tax sale.

Property owners can’t appeal a sidewalk bill, but those who are noticed with special assessments have the option to protest, city spokeswoman Gabby Miller said. No notices were protested the current fiscal year, which started July 1, 2022.

What triggers a sidewalk repair bill?

A few houses down from the Gipsons, Emma Moore received a bill from the city for $9,090 to repair small cracks and holes in the sidewalk.

Exactly what triggered the city’s action in Moore’s case is unknown, Miller told The Bee. The process generally starts with an anonymous complaint of a defective sidewalk, followed by a city inspection in both directions up to 75 feet from the site to see if it is safe for pedestrians and to prevent the homeowner from being sued.

If a bill is sent, the amount the city includes in the bill is the amount the homeowner is charged if it chooses to have the city contractor repair the sidewalk, Miller said. Homeowners also have a choice to hire another licensed contractor to repair it instead.

Moore bought her duplex in 2004, where she lives with her two kids and two grandchildren, ages 3 and 15. Like Gipson, Moore assumed the city’s sidewalk bill must have been sent by mistake. Desperate to get the bill decreased, Moore called the city inspector to come back out and reinspect the sidewalk, which appears to lack major damage, cracks or holes.

“He showed me this three-inch crack and said, ‘if someone was walking through here with a cane and it got caught in this little hole, and he tripped, you would be liable for it,’” Moore said.

Moore was warned that if she did nothing, she risked a lien. Moore, who works as an educator at the Crocker Art Museum, felt she had no choice but to pull it from her savings, delaying her retirement.

“When we got the letter, it caused for worry, worry, worry,” Moore, 64, said. “We don’t even feel the sidewalk is our responsibility. We feel it’s the city’s.”

In the end, she chose to hire a contractor on her own, bringing her expected bill down from $9,000 to between $5,000 and $6,000, she said.

Who’s doing it differently?

Not all California cities charge property owners for sidewalk repairs. While San Francisco, Fresno and San Jose also charge property owners, Los Angeles does not charge for initial repairs. San Diego often pays a portion of the bill to ease the burden on property owners.

Los Angeles received federal funding to fix sidewalks in the 1970s, and kept paying after the funding ran out, according to the Los Angeles Times. A large backlog of sidewalk repairs and a class action lawsuit led city officials to pledge more than $1 billion for sidewalk repairs in the mid-2010s. The city also adopted a “fix and release” policy at the time pledging to fix a sidewalk, issue a limited warranty and then turn over responsibility for maintenance to the property owner.

San Diego launched a new program this month that waives permit fees of up to $2,100 for sidewalk repair projects. The city also allocated about $300,000 to fix sidewalks in underserved areas.

Sacramento’s sidewalk policy has been in the city code since 1978, and was last amended in 2010, when council allowed a temporary repair method called grinding, which is typically 30% cheaper, Miller said. To shift the cost fully to the city would require council action.

The city’s Fine and Fee Justice program, started last year, is designed to lessen the cost burden of various city fees on low-income residents. But the program currently only covers a portion of the fees for getting a vehicle back after it’s towed by police — not sidewalk bills.

After reviewing The Bee’s findings, Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said he would ask the city auditor to look into the issue.

“It’s never a bad idea to review a long-established practice, and I’ll be asking our city auditor to take another look at our complaint-driven sidewalk repair process to make sure that it is not unfairly burdening the people who can least afford to pay,” Steinberg said in a statement.