Missouri holds nation's first execution during coronavirus pandemic

A Missouri man convicted in the 1991 killing of his former landlord was executed Tuesday evening, becoming the first death row inmate to die in the United States since the coronavirus outbreak was declared a global pandemic in early March. The ACLU confirmed the execution.

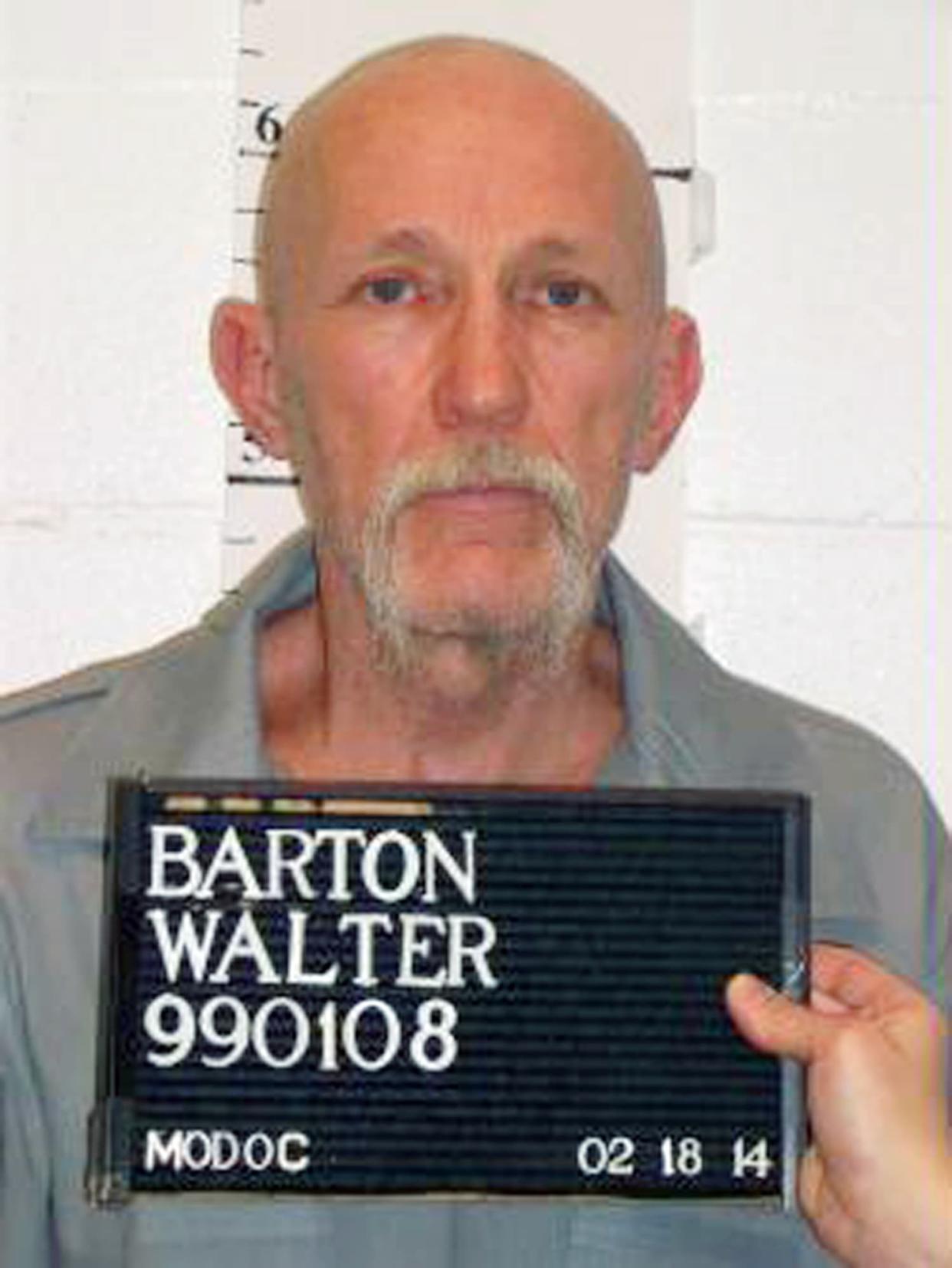

Walter Barton, 64, died by lethal injection in a state prison in Bonne Terre, south of St. Louis, Missouri corrections officials said. Despite pleas in recent days from supporters and his defense team calling into question whether he was wrongly convicted of murder, Gov. Mike Parson said Monday he would not stop the execution.

Other states, including Ohio, Tennessee and Texas, have postponed scheduled executions while corrections officials handle the deepening health crisis, which has overwhelmed many correctional facilities across the country.

AP

Barton had been tried five times for the murder of Gladys Kuehler, 81, who operated a mobile home park south of Springfield, Missouri. Barton, a former tenant of Kuehler's, was living out of his car and reportedly visited Kuehler's granddaughter and a neighbor at the property on the night she was beaten, sexually assaulted and stabbed 52 times.

While blood was found on Barton's clothing, he maintained his innocence at each of his trials. His case has lingered in the court system over the decades because of mistrials and appeals. A fifth trial in 2006 ended in a guilty verdict and a death sentence.

On Sunday, a federal appeals court vacated Barton's petition for post-conviction relief that might have delayed his execution. The court ruled that there was no new evidence.

But in recent weeks, Barton's attorney, Frederick Duchardt Jr., got affidavits from three jurors who had convicted Barton to agree that they now have doubts about his guilty verdict.

At the heart of the case has been whether the prosecution's blood spatter evidence — a form of forensic analysis that has been questioned in recent years over its accuracy — was properly countered by Barton's defense team at his 2006 trial.

Since then, Barton's current defense team ordered an independent bloodstain analysis. According to the examiner, the small bloodstains on Barton's clothing were consistent with his version of events that night and that the actual killer's clothes would have been soaked in blood, given the victim's wounds.

The Innocence Project and others had attempted to stop the execution, citing unreliable evidence and concerns over how previous state prosecutors have handled convictions of inmates later cleared of their crimes.

Barton's execution was the first in the U.S. since March 5, when Alabama inmate Nate Woods was executed for his role in the fatal shootings of three Birmingham police officers in 2004.

Given the coronavirus outbreak, corrections officials in Missouri said they had to consider precautionary measures involved with planning an execution, including submitting prison visitors to temperature checks and dividing them into three separate rooms for social distancing.