These Skilled Backbones Are Building American Manufacturing

At the core of nearly every functioning manufacturer, you are bound to find a handful of individuals that represent the backbone of a company. Sometimes they enter with the skills ready at their disposal. In other instances, they grow into their roles--learning new skills and growing with every opportunity. For the individuals below, they all took separate journeys to become one of the most important people at their respective companies.

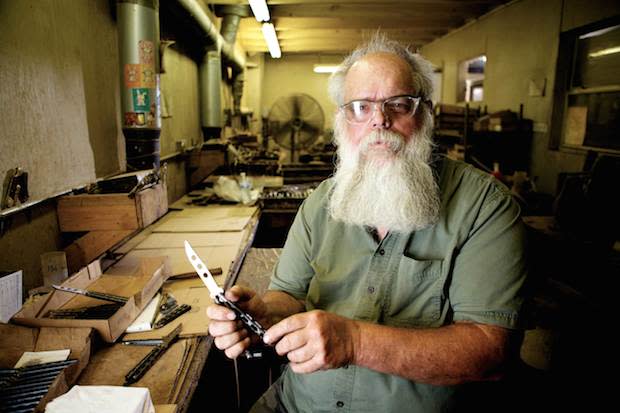

At Alabama's Bear & Son Cutlery, quality control resides in the hands of Stan Nibblett.

Place a knife in his hands--which feel like warm sandpaper from working with honing and sanding equipment for more than 40 years--and he begins working the knife. Called "walking and talking," Nibblett puts the knife through its paces to make sure the blades come out of their resting places and slip back in with precision.

Depending on the knife, he may flip the blades in and out several times, checking that they stay in, so you can "walk" with the knife. But just as important is the "talk": the blade has to slide out smooth, right when you need it. If a knife sticks, it goes back to the sanders where it's reworked until the blade glides like intended.

If the blades are too loose, Nibblett takes it to his cluttered work station filled with small tools, rags and sandpaper to see if he can fix it without sending it back through the line--or worse, having to discard it.

Nibblett can see down to the presses and over to the sanding lines. He's the center of Bear. While his job title is finishing supervisor, Stan is the man who taught almost everyone at Bear the beauty of "walking and talking" a knife. Hand anyone a knife in factory and they mimic his movements.

It's easy to look up to Chris Harmon, and not just because he's 6'4". Harmon, 42, is one of New Ravenna Mosaics' best-known and beloved employees. Like Baldwin, he has roots on the Eastern Shore of Virginia--his family has called it home for three generations.

Up until 12 years ago, Harmon had worked at the Perdue Chicken Plant, one of the few large-scale employers on the Eastern Shore. But he yearned for more.

The job working at the chicken processing factory was stable, but Harmon knew it was taking him nowhere. When he saw an ad for New Ravenna, Harmon was intrigued. After learning more about the company, Harmon was convinced New Ravenna had a bright future and would allow an employee like him to grow. One day after applying for a job cutting stone, he got the call for an interview. Less than a week later, he had the job.

Affectionately known as "Mr. New Ravenna," Harmon has worked his way up from gang saw technician to managing the material preparation department. He remembers his first job, feeding slabs of marble and stone, through a massive saw. But where others may have seen monotony, Harmon was eager to learn a new craft.

"The hardest part of the job is learning all the colors," he says. "You're on your feet the whole time you're working on the gang saws. The hardest part is walking from one end to the other because you have to feed it and catch it. You have to have attention to detail when you're operating the gang saws, because if you don't, you're going to cut something wrong."

Jeff Naslund is the field department manager for Iowa's American Pop Corn Company. He matches hybrid strains to methods and soil conditions of each farmer and monitors the crops through the summer.

The hybrids, the result of a program American Pop Corn began in the '70s, showed their mettle in late June. A violent storm came through the region, bringing softball-sized hail. It ravaged some nearby JOLLY TIME growers' fields, and Naslund wrote off unsalvageable acres and penned letters for the growers' crop insurance.

They avoided the worst of it. Where earlier generations of popcorn might have "gone over," the sturdier hybrid plants weather big storms better. Their backend payoff is palpable too: the hybrids yield 6,000 pounds of corn per acre versus 2,500 pounds in generations past.

"Somewhere along the line when you're doing business, something's going to go wrong," Naslund says. "And not everybody handles it with integrity. And doing the job I do, you can do that, knowing you've got full support and you don't have to be someone you're not. If [farmers] make money and do well, we normally get quality popcorn--they kind of go hand-in-hand."

See More Made in the USA Stories