Okabashi's Shoes Are Japan By Way of Iran By Way of Georgia

Buford, Georgia looks a lot like thousands of other suburban towns across America. There's a town square and playgrounds. There are soccer fields and white picket fences. People commute the 39 miles into Atlanta every morning and back home in the evening.

But under the suburban gloss, Buford is steeped in the history of leather and shoes.

In the early 1900s, Buford rose to prominence as an integral part of the American and international leather trade. First known for making leather horse collars and saddles, the city's factories shifted their focus in the 1920s to shoes, made from the cast-off leather of newly cut horse collars. During World War II, Buford was home to a factory run by the U.S. Army that manufactured and repaired millions of boots for American soldiers.

From the 1950s through 1981, Buford was known both in America and abroad as "the leather city." But in 1981, a massive fire destroyed the Bona Allen Factory, one of the cornerstones of the city's industry. It crippled the company, and could have been the beginning of the end for the town's shoe business.

By 1984, when Bahman Irvani, an Iranian immigrant who had left Iran during the 1979 revolution for London, decided to settle in Buford to run his family's investments in Georgia's shoe business, Buford was no longer "leather city," but was quickly becoming part of the fast-growing suburban sprawl spreading north from Atlanta.

Chapter One: From Leather To Plastic

While Buford had been known for leather, Irvani focused on plastic--notably injected-molded plastic--that could be turned into shoes of all shapes, sizes, and colors. The company's name, Okabashi, derives from the Japanese principles of reflexology, and the emphasis the company puts on making shoes that hit the pressure points on the wearer's feet.

But even though the company had been imbued with international qualities, Irvani was determined to make shoes in America, despite the fact many domestic shoemakers had moved their operations overseas.

"We know manufacturing, we are not importers," Irvani says. "We've always been in that mindset and have stuck to our goals from day one, to manufacture shoes in America. (With) every gain there is always a risk, China may have been less expensive, but there is risk in China."

At the back of the Okabashi plant, a large American flag hangs from the factory's ceiling to serve as a daily reminder to the people working there of the company's commitment to making shoes in America--and in Georgia.

This year, the company celebrated its 30th anniversary and more than met Irvani's goal of making a million shoes per year. Okabashi now makes 1.5 million shoes a year, which are made from up to 25 percent recycled plastic. They sell at retailers like Wal-Mart, CVS, and Walgreens, but the company also has started another higher-end line of shoes called Oka.B that are sold to spas and boutiques.

Chapter Two: The Creator

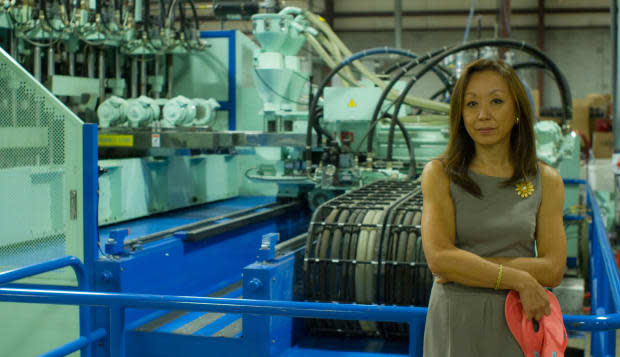

While Okabashi makes millions of shoes, they start out as singular visions in the minds of the company's team of designers, overseen by creative director Naomi Wakatake.

She's a tall, elegant woman who would seem more suited to a Madison Avenue corner office than a plastic shoe factory in the American South. And indeed her path to Buford and Okabashi, like Irvani's, involves thousands of miles.

Born and raised in Japan, she spent 16 years in Hawaii before moving to Atlanta to study sculpture and interior design at the Atlanta College Of Art.

But a meeting with Irvani, set up by her interior design professor, changed the course of her life. In the meeting, Irvani paid no attention to her resume; it was her artistic eye that he liked. "I met with him, and showed him my portfolio, and he was totally not interested in it, but said well, would you be interested in designing shoes," she remembers. "He explained to me the processing method, the mold injected shoe. I was heavy into bronze casting, so I thought 'Oh well, bronze, plastic, what's the difference, it's molds.' So the whole concept, it didn't feel foreign to me."

Irvani says he doesn't mind taking risks on people as long as the foundation is right. "The foundation is their skill set, enthusiasm and commitment," he says.

While the Okabashi factory with its rumbling machines is a long way from an art studio or a museum, Wakatake is happy with where her career has led her. "It was kind of a happy accident," she says. "I just stuck with it, it's almost a dream come true job for a sculpture major. To end up in a job that actually allows me to be artistic and design something."

Wakatake also likes the close interaction she has with the manufacturing team, a benefit of Okabashi's smaller, family-oriented structure. Irvani only hires people who are hands-on, he says. "We don't like bureaucracy, we can't afford bureaucracy," he says. "We like to hire people who like to do multiple jobs. Everyone does whatever it takes."

A flatter, smaller organization also means communication happens faster between design and manufacturing. "Here, if something is not right, you can go directly to the person molding the shoes," Wakatake says. "You can talk to them, and resolve it. So that's a very secure feeling, I think. If there's a problem, we can talk about it and solve it. We're all part of the process."

Chapter Three: The Dreamer

Twenty-five years ago, Daniel Zaharia, the leader of Okabashi's first manufacturing shift, was just 13 years old, staring out of the window of an airplane at the glow of New York City below. His family was fleeing their home in Romania as the country spiraled into chaos.

The bright lights of New York were a stark contrast to the darkness and power outages that were routine in Romania. "Everyday, they shut the lights off," he says. "Flying over New York, you see nothing but lights, and it looked like the entire city was on fire. I said, 'Well, I guess nobody has a problem with lights here.'"

Zaharia's family settled outside Philadelphia. He learned injection molding in high school and worked at Graco Company, which makes child seats among other plastic products. He also got married and that brought the shift from the industrial north to the south. His wife wanted to be closer to her family in Georgia, so he applied for a job at Okabashi as an operator of the mold machines on the factory floor.

Six years later, Zaharia is now a leader of Okabashi's first shift. He has two sons and he and his wife own their home in Buford. His perspective on 'American made' is a bit richer than most. "It's a big deal, you know. We can do it," he says. "We've done it before, everything used to come from the United States. So yeah, it has meaning for me."

Any morning during Okabashi's peak production season, you can see the power of that manufacturing history move through the factory. Zaharia's first shift is starting just as the third overnight shift is coming to a close. Okabashi's management and executive team are arriving for the day and a sharp image of America at work comes into focus.

"That time of day is the greatest sense of community," says Chuck Headrick, Okabashi's vice president of manufacturing. "Just for that short period of time, that's when you get to see here at this factory what people buying our shoes are keeping alive."

For Headrick, who supervises everything at the 100,000-square foot factory, it's people like Zaharia who embody the spirit of Okabashi. "Daniel is a perfect example of that," he says. "He's a guy that came here as an immigrant, seeking a better life, came down here and was on third shift when I got here. Now he's on first shift, and he's the key guy in our molding department everyday."

At Okabashi, putting a premium on American manufacturing has helped the company grow over the last 30 years. But the diversity of the workforce also is compelling, as Irvani says, "Once the company has diversity embedded in it, then people apply and people like to join (this kind of) team. Diversity attracts diversity."

For Zaharia, Okabashi's belief in diversity helped him make the journey from a 13-year-old staring down at a brightly lit city or even as a young man in Philadelphia. "In Pennsylvania, my old house, the backyard was almost non existent," he said. "I wasn't able to put up a fence. But here, you almost have a park in the backyard. So that made a big difference for me. And I was able to afford a house, so it's a long way from where I originally came from, yeah."

See More Made in the USA Stories