Austerity and Depression in Ireland

Europe's deteriorating economic situation continues to dominate the financial headlines. Fortunately, much of the news this month has been positive. Greece managed to default in an orderly manner two weeks ago. And earlier this week, Italy successfully auctioned off 2.817 billion euros of zero coupon bonds near the upper end of its target range.

Yet the reality is that the continent remains mired in fiscal woes so serious that they threaten the monetary union's very existence. Perhaps no country exemplifies these problems more than Ireland, which throttled its economy into depression by guaranteeing the debts of its largest banks in 2008 and 2009 and subsequently agreeing to undertake a series of fiscal reforms, known euphemistically as "austerity."

The Celtic Tiger's roar turns whimper

For much of the last 20 years, economists and policymakers watched in amazement as Ireland's economy took flight. Called the Celtic Tiger after the rapidly growing East Asian economies, the country grew at a blistering pace. From 1995 to 2000, its economy expanded at an average annual rate of 9.7%. And from 2000 until 2008, it grew at the lesser but still impressive rate of 5.5% a year.

While the causes of this success are subject to debate, credit is typically given to a number of state-driven economic reforms. Among other things, the country lowered its corporate tax rate, invested heavily in higher education, targeted foreign direct investment, and adopted the euro as its official currency in 2002. At the time of the financial crisis, companies like Dell, IBM, Apple, and Hewlett-Packard had all established sizable operations in Ireland. By one estimate, the country produced 25% of all European PCs.

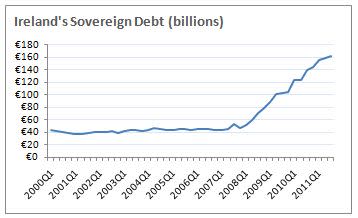

As the saying goes, however, all good things must come to an end. And nowhere was this truer than in Ireland during and after the economic downturn. To avoid the imminent collapse of banks like the Bank of Ireland (NYS: IRE) , the small island nation nationalized its largest lenders and throttled itself into debilitating indebtedness. Its pre-crisis cyclically adjusted debt load quadrupled from a manageable 50 billion euros in 2007 to an overwhelming 160 billion euros today. Its debt-to-GDP ratio, an important measure of a country's fiscal health, increased from 25% to above 100% over the same time period. Its interest payments alone now take up nearly 10% of the country's declining revenues.

Source: Eurostat.

While it'd be nice to say that the bad news for Ireland ended there, the reality is that these initial stages were just that, initial stages. Forced by foreign lenders to enact a series of strict austerity measures aimed at decreasing its annual deficit, the country has seen its fiscal and economic woes worsen to the point of depression. Let me reiterate this point for emphasis: While the precise definition of an economic depression is elusive, there's little doubt that the austerity measures imposed on Ireland have propelled the country into its unenviable embrace.

The most immediate symptom of the country's travails concerns the collapse of its economic output, as evidenced by its gross domestic product. Although most Western economies saw their outputs contract in 2009, Ireland's contraction is unique in both its depth and duration. From peak to trough, its GDP has declined by 20%. By comparison, despite all the attention Greece has garnered throughout the crisis, its GDP fell by a comparatively modest 7%. To make matters worse, moreover, Ireland's is still contracting. Its most recent year-over-year quarterly decline of 1.9% was the 14th in a row. Think about that for a second. As bad as it was here in the United States, our real GDP contracted for only four consecutive quarters and at its worst was down a mere 5% from the peak.

Sources: Eurostat, author's calculations.

The impact on the average Irish citizen is illustrated best by the trend in the country's unemployment rate. Between 2000 and 2008, its natural rate of unemployment resembled ours here in the United States, coming in around 4%. Following the downturn, however, the number of unemployed Irishmen and -women more than tripled. The figure now stands at 14.8%. And like its GDP, this too continues to deteriorate. In December of last year, the figure stood at 14.7%. A year ago, it was at 14.4%. Your guess is as good as mine in terms of where it'll be next year, but the trend isn't good.

Sources: Eurostat, author's calculations.

Under normal circumstances, Ireland's economy would right its own course somewhat naturally. As output fell, foreign investors would pull capital out of the country and thereby cause the relative value of its currency to fall. This would increase the competitiveness of exports from Irish companies like pharmaceutical maker Amarin (NAS: AMRN) , biotech company Elan (NYS: ELN) , and disk drive maker Seagate Technology (NAS: STX) . Ireland's current account balance would thereby increase and drive Ireland's output and employment back in the positive direction.

Because it's a member of the European Union's monetary bloc, however, these forces aren't allowed to operate. While it's true that the euro has lost value since 2008, this has done little to nothing for Ireland. In the first case, as alluded to above, most of Ireland's exports go to Europe, which negates the benefit of a depreciated euro. And in the second case, the magnitude of its correction isn't commensurate with Ireland's economic needs. Whereas Ireland's GDP decreased by 20%, the euro has declined in fits and starts by a maximum of only 16%. The net result is that Ireland will continue to flounder about under an unconscionable debt burden until it either pays it off, defaults, or defects from the euro -- none of which are desirable alternatives.

What's an investor to do?

For the investor, there are two ways to play this situation. In the first case, one could exploit the depressed value of Irish companies. This is the course recommended by our Motley FoolSpecial Ops newsletter, which recently advised its members to stake a position in Bank of Ireland. Alternatively, you could seek safety in powerful, yield-producing American companies like the three identified in our free report "3 American Companies Set to Dominate the World," one of which is up nearly 50% in the last two years alone. While there are advantages to either course, the one I prefer is set out in the latter report. To learn the identity of the three companies recommended therein, I urge you to download the report while it's still available. To do so, click here now -- it's free.

At the time thisarticle was published Fool contributor John Maxfield has no financial position in any of the companies listed above. The Motley Fool owns shares of Apple and The Bank of Ireland.Motley Fool newsletter serviceshave recommended buying shares of Apple.Motley Fool newsletter serviceshave recommended writing covered calls on Dell and creating a bull call spread position in Apple. The Motley Fool has adisclosure policy. We Fools may not all hold the same opinions, but we all believe thatconsidering a diverse range of insightsmakes us better investors. Try any of our Foolish newsletter servicesfree for 30 days.

Copyright © 1995 - 2012 The Motley Fool, LLC. All rights reserved. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.