Get Ready for an Earnings Bust?

Think about this: Since 2008, gross domestic product has increased 6.4%, but corporate profits have jumped 27%.

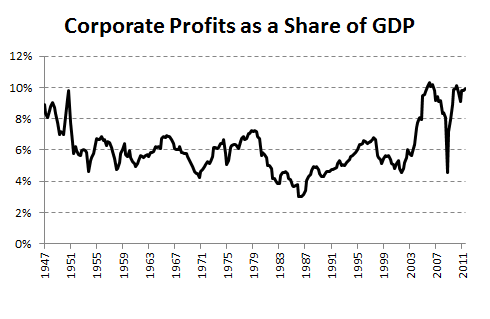

How can profits grow so much faster than the economy? Because profit margins have been surging. In fact, corporate profits as a share of GDP are nearing an all-time high:

Source: Federal Reserve.

This scares some. As fellow Fool Alex Dumortier explained last year, profit margins tend to be mean-reverting over time. With margins at what look like cyclical highs, companies could be in for a big margin bust over the coming years. Corporate profits are now "freakishly high," according to famed investor and financial historian Jeremy Grantham. His colleague, Ben Inker, added, "The implication for the stock market is ugly, because it means earnings are unsustainably high."

This may indeed be cause for worry. The economy itself seems destined for slow growth. If margins fall, profits will grow slower than the overall economy. With stock valuations not exactly cheap, that could very well send markets like the Dow Jones Industrial Average (INDEX: ^DJI) lower.

But before you run out and panic, there could be another side to this story.

First, falling margins do not automatically mean falling stocks. Margins fell by over 50% from the late 1970s through the mid-1980s, and stock prices more than doubled. Margins declined by a quarter during the late 1990s, and stocks surged. Conversely, margins increased substantially during the 1970s, and stocks plunged. The past decade saw one of the largest increases in profit margins ever, and it was also one of the worst decades for stocks in modern history. If there is a connection between margins and stock returns, it might be the opposite of what seems intuitive.

But the most relevant question in this debate is why margins are at an all-time high. Here, I think there are three points to keep in mind:

Wages as a share of GDP are at an all-time low. Since wages are most businesses' biggest expense, low wages (due to high unemployment) help keep profit margins high.

Corporate taxes as a share of GDP are the lowest they've been since the 1930s. That, too, helps keep profit margins high.

Business investment in technology equipment is at an all-time high. This helps make businesses more efficient (doing the same work with fewer employees), which pushes margins higher.

All three have different implications on the future of profit margins.

Higher wages (primarily from lower unemployment) could cause profit margins to decline, but with it comes an obvious counterweight: More hiring means more consumer spending, more revenue, and faster growth. I don't think anyone, even Grantham, would argue that the economy is going to plunge once businesses resume hiring.

Investing in technology equipment not only promotes higher profit margins, but the gains may be long-lasting. As I've shown before, recent history has been the story of less economic growth going to workers and more going to corporate profits. That trend isn't cyclical; it's been steady for nearly 40 years. Two recent books, Race Against the Machine and The Great Stagnation, argue convincingly that this trend isn't going away anytime soon.

Taxes could be a different story. Corporate taxes as a share of GDP are low right now largely because many businesses lost a tremendous amount of money in 2008, and now have large tax-loss carryforwards to offset current tax liabilities (one reason why, for example, General Electric (NYS: GE) allegedly paid no taxes in 2009). That won't last forever, and assuming current tax rates stay the same, taxes paid should increase in the coming years, causing both margins and after-tax profits to fall.

Another important point to consider is how the composition of American business has changed in the last several decades. One of the biggest shifts has been the rise of the financial industry. In 1947, finance made up 2.4% of the economy. By 1970 it was 4.2%. By 1990, 5.8%. In 2010, it was a whopping 8.4% of economic output -- an all-time high.

That can distort overall profit margins for a couple reasons. Financial profits tend to be wildly volatile, as the performances of Bank of America (NYS: BAC) and Citigroup (NYS: C) have proved. Financial margins can also be far higher than other traditional industries, particularly in the financial services and trading sectors. Goldman Sachs (NYS: GS) , for example, had profit margins of over 27% in 2009, far above the broader average.

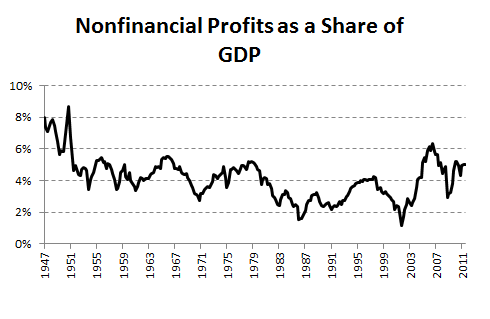

So what happens when you remove financial companies from the equation? Nonfinancial corporate profits as a share of GDP are still high, but not "freakishly" so. In fact, nonfinancial profit as a share of GDP is a mere one percentage point above the long-term average, and still below levels seen in the 1960s and 1970s:

Source: Federal Reserve.

What's it all mean? In short, not much. The argument that profit margins are bound to fall isn't as strong as it might seem, and even if they do fall, evidence that it will bring down the stock market with it is selective at best. As always, the key is buying quality companies with strong moats at good prices and hold them for a long time, with a commitment to being impervious to volatility. Everything else, as they say, is noise.

At the time thisarticle was published Fool contributor Morgan Housel owns Bank of America preferred. Follow him on Twitter @TMFHousel. The Motley Fool owns shares of Bank of America. Motley Fool newsletter services have recommended buying shares of Goldman Sachs. Try any of our Foolish newsletter services free for 30 days. We Fools may not all hold the same opinions, but we all believe that considering a diverse range of insights makes us better investors. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Copyright © 1995 - 2011 The Motley Fool, LLC. All rights reserved. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.