SC elections officials are leaving in record numbers. What will it mean for midterms?

As director of the Dorchester County Board of Elections, Todd Billman saw himself as a community advocate working to advance the democratic process by conducting efficient, fair and accurate elections.

He was passionate about the work, having climbed the ranks from part-time employee to director in just eight years, and aspired to a long, fulfilling career in election administration.

Then came the 2020 election cycle, and with it a surge of public scrutiny and skepticism about his work like he’d never experienced.

“It came to a point where I went from a job no one knew existed to a job where everyone thought they knew how to do it better,” said Billman, 41, who resigned in January and now works as an account manager for an election software company.

Billman is one of 22 South Carolina election directors across 19 counties who have left office since the 2020 general election. Two others have announced plans to leave at the end of the year.

“People like me are now seen as the problem, not part of the solution,” Billman said. “I always wanted to be part of the solution, and at this point, I didn’t see that changing because of the political climate.”

The state historically turns over less than a handful of director positions every couple years, said State Election Commission Deputy Executive Director Chris Whitmire, who called the recent departures “unprecedented.”

“A lot of institutional knowledge has walked out the door,” he said. “We’ve never seen even close to this as far as the turnover.”

The exodus of election officials is not unique to South Carolina. A recent survey of nearly 600 local officials across the country found that one in five reported they were unlikely to continue serving through the 2024 presidential election.

Escalating attacks on the integrity of the election system, intensifying political divisions in the country and excessive job-related stress were among the top reasons officials cited for leaving the profession, according to the survey conducted on behalf of the Brennan Center for Justice.

Each departing director in South Carolina had their own reasons for leaving. The polarized political climate and persistence of discredited 2020 election fraud claims played a role for some, but not all directors.

A few left to take jobs running elections in larger counties or were hired by the State Elections Commission. Others moved into the private sector or retired.

The exodus of election directors, which left South Carolina with 17 counties where the chief election administrator had never conducted a statewide general election, could have significant implications for the midterm elections in November.

Because there’s no uniform standard for election directors, academic credentials and professional experience vary widely between individuals. Some are high school graduates with limited work experience while others have advanced degrees, Whitmire said.

The State Election Commission has worked to train the new directors, four of whom had never worked in an elections office prior to being hired, but there’s only so much that can be gained from orientations, workshops and walk-throughs.

“You have to learn by doing,” Whitmire said. “All of the weird situations, the unique situations you can run into and you have to determine how to handle. A lot of that comes from experience.”

Why are election officials leaving?

State and local elections officials have come under a deluge of pressure since 2020, when COVID-19 upended the country and forced leaders to adapt public elections to protect the safety of voters and poll workers.

Adding to the stress of conducting a massive civic event amid a deadly pandemic, opinions about proposed modifications to the election process were irreconcilably split, often along partisan lines.

Democratic politicians in the state by and large supported expanding mail-in voting, eliminating the witness signature requirement on absentee ballots and using drop boxes to collect those ballots as a means of ensuring voters could safely participate in the electoral process.

Republicans, on the other hand, were largely skeptical of such attempts to ease access, arguing they would exacerbate voter fraud and diminish election integrity, a concern that has animated the party for years.

Elections officials were caught in the middle, asked to implement a dizzying series of new measures – some of which changed by the day based on court decisions – and under increasing strain from people of all political stripes.

The situation only intensified after the votes were counted on Election Day, as former President Donald Trump and other prominent Republicans and right-wing media outlets began relentlessly pushing the unfounded theory that the election was stolen.

“After the election, certainly, election officials didn’t get a big pat on the back,” Whitmire said. “We’ve received a lot of criticism from groups and individuals who doubted the results of the 2020 general election, and that has been stressful for election officials, not just in South Carolina, but across the United States.”

The myth of the stolen election, which inspired rioters to storm the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, persists despite multiple recounts and audits finding no evidence of systemic voter fraud.

Even in a red state like South Carolina, which Trump won by nearly 12 percentage points and where Republicans expanded their majorities in the Legislature in 2020, skepticism about the election abounds.

Whitmire said he initially assumed election deniers wouldn’t challenge results and processes in a state their preferred candidate won, but now realizes he was naive.

“We expect scrutiny, scrutiny’s a good thing. It makes us better,” he said. “But what we’ve been getting is unprecedented, baseless, unfair scrutiny. We’re dealing with beliefs rooted in lies.”

Public interest in elections and the processes that undergird them has increased markedly since 2020, driven by people convinced the system is corrupt and skeptical of the motivations and loyalties of election workers.

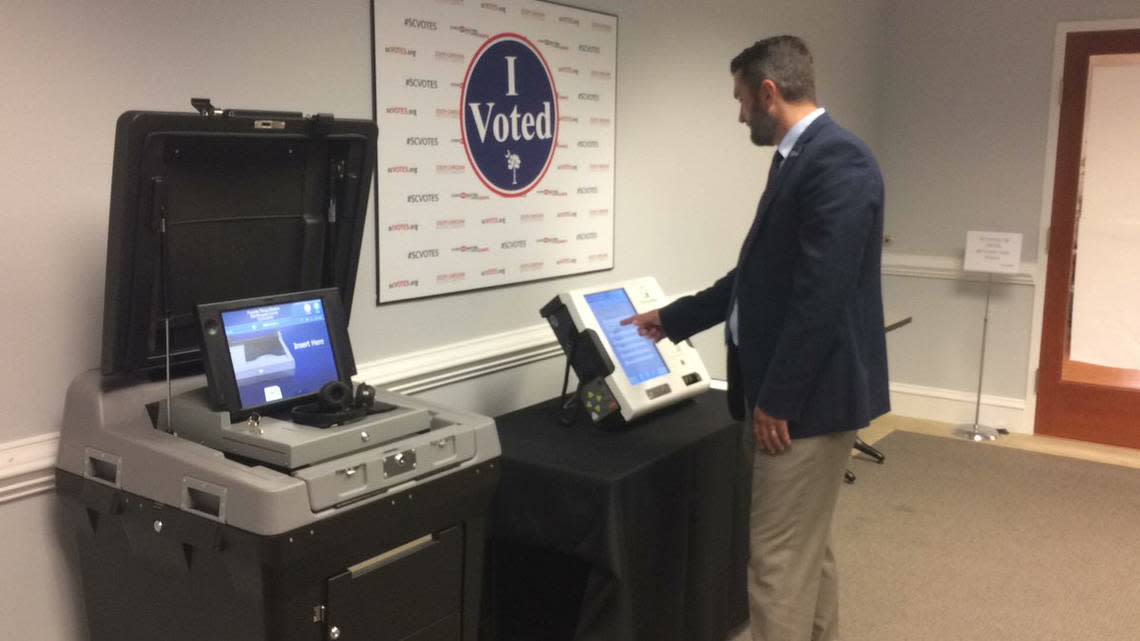

Officials are fielding countless questions about computer systems, election machinery and ballot processing protocols. Tours of elections offices and public tests of voting equipment that previously had drawn scant interest now attract considerable attention. And public record requests seeking documents referenced in the latest election conspiracies are pouring into state and county voter offices, overwhelming officials in the process.

As of Friday, the State Election Commission had received a record 159 Freedom of Information Act requests this year, roughly 5 times the typical volume, according to Whitmire.

The vast majority are “frivolous,” he said, and seek information related to election integrity. Many contain identical language and appear to have been submitted by devotees of prominent election deniers who have asked followers to flood elections offices with requests that some have described as denial-of-service attacks on local government, a reference to a type of cyber bombardment meant to paralyze a computer network.

“No offices, state or county, are really equipped to handle that volume,” Whitmire said. “I don’t think any organization is equipped to handle a 500% increase, an exponential increase in any work output.”

In addition to the avalanche of inquiries, officials have reported an uptick in threats and intimidation from election skeptics who accuse them of perpetrating an elaborate cover-up.

The vast majority of local election officials who responded to the Brennan Center survey reported that the frequency of threats against election workers had increased in recent years. One in six local election officials have experienced threats and nearly one in three reported knowing an election worker who had left their job at least in part due to threats, intimidation or fear for their safety, according to the survey.

The U.S. Justice Department’s Election Threats Task Force, which just wrapped up its first year of work, reviewed more than 1,000 contacts reported as hostile or harassing by the election community, according to an August news release. Approximately 11% of those cases met the threshold for a federal criminal investigation and charges have been filed in four of those cases, the department said.

Charleston County Elections Director Isaac Cramer, who has worked in the elections office since 2014, said he’d never been harassed or threatened until Election Day 2020, when a man who had missed the voter registration deadline accused him of acting illegally and threatened to attack him.

“We had to get a security guard involved,” he said. “I was shaking. You’re trying to be calm in the moment, but you just don’t know. You worry about your safety first.”

Cramer said he’s since grown accustomed to threats and intimidating behavior and now trains poll workers to be acutely aware of their surroundings and report suspicious activity.

During this year’s primaries, he said he called police on a group of poll watchers who were harassing election workers and creating an environment that made it difficult for them to do their jobs. Two weeks later, during a runoff, the same observers, who are members of a local group that contests the outcome of the 2020 election, were out again in force.

“For all of you on the team tomorrow observing the polls, Good Hunting,” a June 27 Facebook post by one of the group’s leaders reads. “You know what you are looking for. We have the enemy on their back foot, press the attack. Forward.”

The next day, the group’s members barged into polling places with cameras and video recording devices asking to inspect election equipment. They brought police officers with them to report what they claimed were broken or missing seals on voting machines that they accused election officials of using to tamper with votes.

“That’s intimidating,” Cramer said. “If someone runs into your polling place with a camera, you don’t know what they’re doing. If I’m just doing this as my civic duty to give back to the community to serve this county and country, I don’t want to do that anymore.”

While Whitmire said he wasn’t aware of any explicit death threats against South Carolina election workers, he said repeated attacks on their integrity had nonetheless taken a toll.

He shared a series of emails a man sent last year to the former York County elections director in which he claimed the county’s results were “riddled with fraud” and exhorted her to come clean about her role in subverting the election.

“We will Not rest until the individuals that participated in this treason are held accountable,” the man wrote. “If you or anyone else is aware of fraud, now would be a great time to come forward and perhaps cut a deal. This will Not end well.”

Multiple elections officials expressed frustration that their attempts to engage with skeptics and clear up any misconceptions about the process often failed to satisfy them.

“It is maddening because using logic and common sense and trying to talk through things doesn’t work,” Whitmire said. “At the end of the day, it feels like you’re arguing religion with someone and it’s not going to be a fruitful conversation at all because they have beliefs and facts don’t matter.”

Billman, the former Dorchester County director, said he spent many hours responding to public record requests and meeting with disgruntled voters in an attempt to clear up any misconceptions, but ultimately concluded that nothing he could do or say would convince them the process wasn’t rigged.

He said he knew it was time to step away from the job last year after he snapped at an election denier during a public test of voting equipment.

The woman, who had been traveling the state observing the process in various counties, asked Billman to open the ballot scanning machine to prove there wasn’t a modem inside. He declined because doing so would have rendered the equipment inoperable.

She accused him of hiding something. So he asked rhetorically if she had a brain. Prove it, he said he told her. If he couldn’t see it, he wouldn’t believe it.

“I realized when I was that harsh with someone I had lost my trust and patience in people,” Billman said.

It’s not surprising that some election workers are leaving their jobs, given the level of disrespect and scrutiny they face on a daily basis, said Lynn Teague, vice president for issues and action with the South Carolina League of Women Voters.

“Who wants to go to work and be accused every day of some terrible behavior?” she said. “We are deeply concerned about election workers being demonized unfairly.”

Teague said the League has audited elections for years, and while it occasionally finds defects, none have pointed to fraud or would have changed the outcome of an election.

“The notion that our county and state officials are somehow plotting to create defective elections, which is an accusation that’s actually being made, is concerning,” she said. “We’ve seen very dedicated people in these positions and usually their primary intention is to make sure everyone who can vote does vote and does so without undue trouble within the law.”

Cramer said he knew what he was in for when he accepted the Charleston County election director’s job in April 2021, but understands why so many others in his shoes have moved on with their lives.

“Every day you go to work and everyone sees you as the bad guy,” he said. “You’re hiding something, you’re doing something wrong and you’re under immense scrutiny 24/7, even though you’ve done nothing wrong.”

Inspired to work in elections by his immigrant mother’s own U.S. citizenship journey, Cramer said he remains passionate about the work and has stuck with it because he believes counties need experienced directors to instill stability in the voting process.

However, even he admits he’s become more circumspect in recent years when discussing his job with strangers.

“Most of the time when I meet people I say I work for the local county government, and usually that suffices,” Cramer said. “Because it’s such a polarizing issue right now, and to be a public servant in elections, no matter where you are, people have an opinion about it.”

The risks of inexperienced election directors

With the midterms fast approaching, county election directors are ramping up training in preparation for November.

Clarendon County elections director Sharmane Anderson, a 40-year-old lawyer who had never worked in an elections office until last month, said she feels confident conducting her first election and credited guidance she’s gotten from the State Election Commission and colleagues in neighboring counties.

“I’m feeling pretty good,” said Anderson, who believes her legal background and experience as a poll worker should serve her well in the role. “Of course, the day of (the election) that very well may be different, but we’re trying to do as much preparation as we can beforehand to ensure the election moves as smoothly as possible.”

Whitmire said the State Election Commission has been doing everything in its power to prepare new directors, nearly half of whom have never been through a statewide general election.

“We’re doing director trainings and we have area reps who work directly with those directors, monthly calls with all the directors and we’ll increase the frequency as we go from here forward to the general,” he said. “It’s a challenge, and we’re working hard to overcome it.”

New directors must learn everything from preparing and testing voting equipment to proofing, printing and mailing out absentee ballots. They’re responsible for fulfilling FOIA requests, recruiting and training poll workers, and, of course, responding to any of the unexpected twists that inevitably occur on Election Day.

“Elections are really complicated, especially in this day and age,” said Rachel Orey, associate director of elections at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. “They’ve gotten more complicated over time as the scale of cyber security threats have increased, as public skepticism has increased.”

In addition to mastering administrative tasks, election directors also must excel at communicating with the public, especially in the event mistakes are made, because election deniers often seize on minor issues during vote tabulation to claim officials are manipulating results, Orey said.

“If there is an issue in tabulation, (new directors) may lack the institutional knowledge to explain what occurred and what steps are in place to secure the process,” she said. “It’s that kind of public-facing aspect that may be more difficult for new election directors to accomplish.”

A more pernicious, albeit less likely risk of relying on an inexperienced election director, she said, is the possibility they may unwittingly provide bad actors access to voting machines.

There’s a growing concern among election administrators that law enforcement officers who have been recruited by election denialism groups will attempt to access voting equipment on Election Day, Orey said.

“It’s not always easy if you’re new in this position and this law enforcement officer is asking for access to your equipment and you think you just have to do it.” she said.

Longtime Beaufort County elections director Marie Smalls, who serves as president of the South Carolina Association of Registration and Election Officials, an industry trade group, said she’s confident new directors will rise to the occasion.

Between training from the State Election Commission and consultation with more experienced colleagues across the state, Smalls said new election directors have all the tools they need to succeed.

“They may not do a stellar job,” she said. “But I think they will have enough support where they can conduct their election with some sense of certainty that they’re doing the right thing.”