15th century shipwreck reveals ‘surprising’ cargo and weapons for fending off pirates

While exploring a 500-year-old shipwreck off the coast of Sweden, divers discovered “surprising” cargo and weapons that may have helped repel pirates.

The remains of the wooden vessel lie off the coast of Maderö Island, a Baltic Sea islet located about 20 miles southeast of Stockholm.

Long known to locals, the Maderö wreck was first visited by divers in 1969, who described it as a large medieval trading ship filled with bricks. In the decades since, other divers visited the site, but a complete investigation was never performed, leaving key questions unanswered.

Intent on demystifying the ship’s origins, a team of archaeologists dove down to the wreck in May 2022, where they took over 1,000 photographs and numerous samples, according to a study published on Jan. 5 in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

“Not so much is known about the architecture of these ships so every new wreck that is surveyed increases our knowledge a lot,” Niklas Eriksson, one of the study authors, told McClatchy News in an email.

What archaeologists found

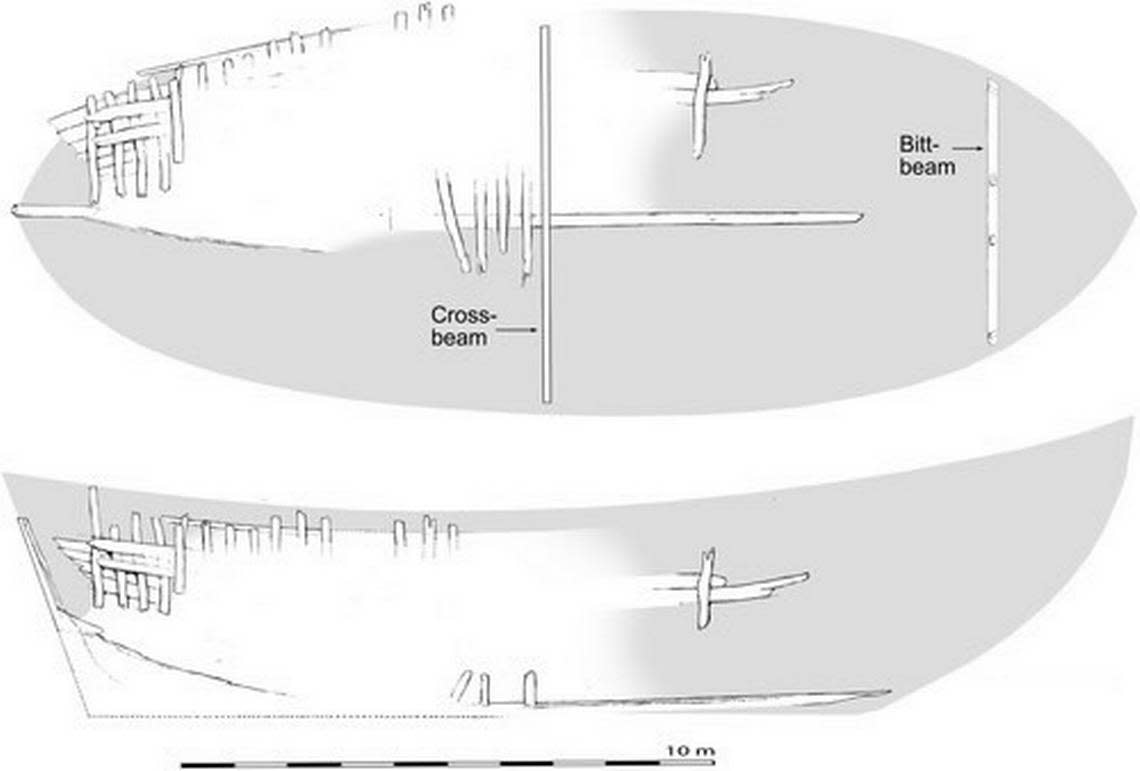

Samples taken from the roughly 50-foot-long oak hull, which lies under about 75 feet of water, were subjected to dendrochronological analysis, a technique for dating trees based on their rings.

Using this method, archaeologists determined the timber had been sourced from various locations throughout northern Europe, and at least some of the wood came from a tree felled in 1467.

“The different origin of the wood suggests that the Maderö ship was built at a shipyard that brought in and imported material from a larger area, rather than relying on locally grown wood,” archaeologists said.

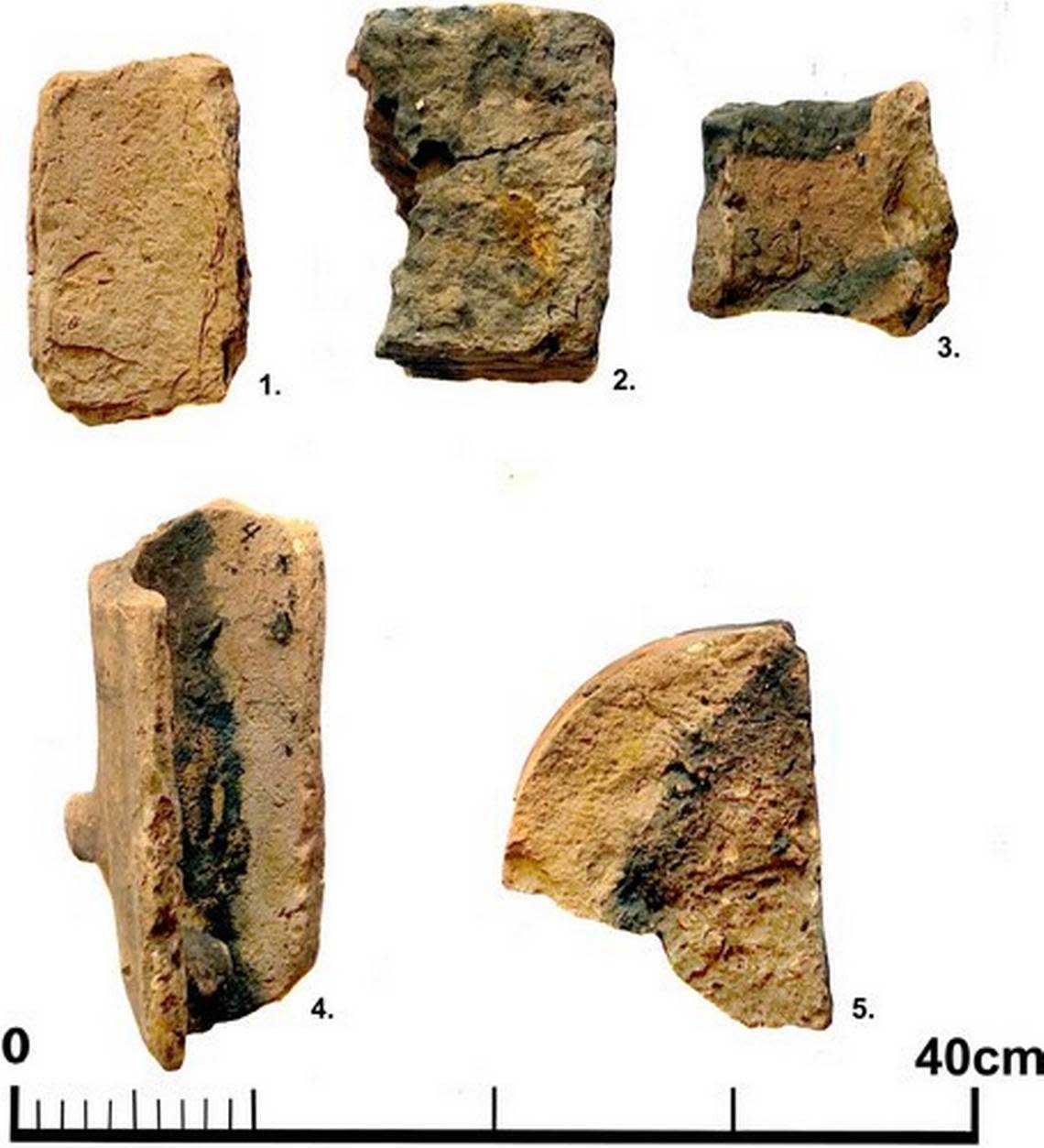

Samples were also taken from the vessel’s cargo, which consisted of roof tiles, rectangular bricks and specialty bricks used to line windows and doors in medieval structures.

Upon chemical analysis of the samples, archaeologists were able to trace them to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, a state in northeastern Germany.

“The provenience of the cargo appears a bit surprising in this context as it has been assumed that the domestic production of bricks and tiles could meet the demand of construction works,” archaeologists said.

The foreign-sourced bricks raise interesting questions about medieval trade in the Baltic region, Brendan Foley, a maritime archaeologist at Lund University, who was not involved in the study, told McClatchy News in an email.

Their points of origin suggest a link to the Hanseatic League, an organization of northern German merchant communities that was a powerhouse in interregional trade.

“There is no other cargo apparent on the Maderö wreck, which raises the possibility that it was organic (grain or other foodstuffs, animals, textiles, etc) or something that would not leave a trace,” Foley said.

Although the discovered cargo indicates the vessel sank during a trading voyage, several cannonballs were also found onboard, suggesting sailors were prepared for something more than a smooth business trip.

In fact, sulfur, an ingredient for gunpowder, was found coating one of the cannonballs, indicating it may have been loaded inside of a cannon at the time the vessel sank, archaeologists said.

It’s not clear how common it was for medieval merchant ships to be armed, but it’s possible they took precautions to protect themselves from pirates.

“During the 14th to 15th century there (was) a lot of piracy on the Baltic Sea,” Eriksson said.

And at the time, when many state-owned navies had yet to be formed, large ships often served dual purposes: to supply goods and defend against attackers, Eriksson said.

“At close ranges and under suitable conditions, shot from wrought iron guns could have inflicted casualties on attacking piratical crews,” Foley said. “These were anti-personnel weapons that could also damage sailing rigs; they were not the hull-crushers of later periods.”

Archaeologists also determined that, based on the location of the wreck, the ship had been sailing towards Stockholm when it went under, meaning it may have been just a few miles from its destination when it sank.

Ancient palace where Alexander the Great became king reopens in Greece. Look inside

Spices still had ‘distinctive aroma’ after being discovered on 15th century shipwreck

Letter from Roman emperor leads to discovery of cult temple hidden beneath parking lot